Half-Life – The Journey

June 21st, 2009

There’s a saying that won’t quite come to mind, it goes along the lines of “life is about the journey, not the destination” The Half-life series epitomizes this mantra very well. The journey of Half-life can sometimes be as much of a detriment as it is a merit, whatever the case, that’s not the discussion point for this article. Instead I want to investigate how the series crafts a believable journey.

Much of this runs parallel to the stringent realism of the Half-life games. For one, both games run in a completely interconnected world where each time Gordon is given a simple task (reach this area). While he passes into obstacles along the way, his one goal remains the same, emphasizing the bond between one journey and one outcome, rather than a series of missions with a developing goal. The game centralizes this one goal with Gordon reaching civilian camps or Black Mesa foot soldiers to have them rephrase his objective, the means in which to achieve it and how he is closer to reaching that objective.

Half-life‘s world is so remarkable because of it’s coherence. Unlike some games which force a suspension of disbelief, everything that occurs in the Half-life games is logical and realistic of that world. If you infiltrate an abandoned enemy base, only a few lowly soldiers will be present. Those Combine soldiers will likely summon reinforcements (or the noise of gun fire will alert other groups), those reinforcements will take some time to arrive to the scene, will be organized into squads of controlled numbers and swarm the area in respects to other squads. In other games, enemy units just spawn and attack in a structure-less fashion and once they find you they don’t co-ordinate their attack patterns in realistic ways.

The whole game is told exclusively through a first person viewpoint and as mentioned previously relies on clues to prompt the player to investigate context. It’s a completely organic method of story telling. The player learns everything about his surroundings through his own observation and narrative is never made compulsory. By fixing the player into this perspective the game does nothing to detract from the experience and overarching journey.

Furthermore the games don’t distract the player with game-based norms which are outside of Gordon’s view. This is perhaps why there is so much quietness in Half-life, because the game mostly concentrates on what is within Gordon’s environmental sphere and not the players. Gordon can’t hear the ambiance crescendo as he walks into unsuspecting danger.

Ah, this is a rather lax analysis, but I’ll leave it there for now. I still have the two episodes to play so maybe my ideas will come to fruition in the meantime.

Additional Readings

Column: ‘The Interactive Palette’ – Grim Fandango and Diegesis

Half-life – Foreplay, First Person Platforming, Implicit Direction and Whitewash Vanilla

June 18th, 2009

I honestly haven’t looked terribly hard, but I’m willing to hedge my bets that it’s rather difficult to find some rant-free criticism of the Half-life series. The truth is I didn’t like Half-life or it’s sequel as much as the universal acclaim would have you believe. At times I frankly wanted to punch a hole through the monitor in sheer frustration, but for the most part I was simply underwhelmed. I want to extensively examine my disliking towards the two games, since such writing is a distant departure from what most people have written on the series.

I’ve built up this angst towards PC games over the past decade. While I enjoyed classics like Jazz Jack Rabbit, Doom as well as a pile of Amiga 500 games as a kid, I can’t stand the uninviting PC games culture that has emerged and subsequently the games that appeal to that culture. I’m mainly talking most big-release PC games post-1996. My twin has taken a huge liking to these games in recent years and his contrast on me has brought my angst to the forefront, so I’ve gone on a crusade to try and break down my ignorant – ‘console boy’ – trepidation, to fall in love with the past decade of PC games.

Honest-to-God truth, I really tried this time. I want to like Half-life and Half-life 2, but I can’t as reasons below explain. On the flipside, I loved Quake when playing it for the first time late last year. So here’s my justification, don’t crucify me, please.

NB: I often use the word Half-life to signify both games, otherwise I will specify when required.

Beyond the Aftermath

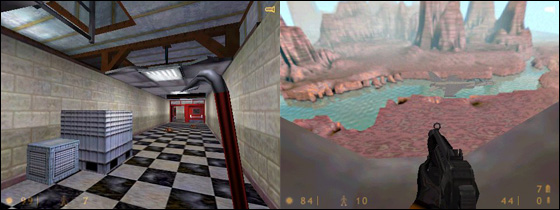

The one immediate impression I reached on the Half-life series was it’s similarity with Metroid, particularly so with Half-life 2. The Metroid games are brilliant at portraying a sense of desolation and atmosphere. Both Half-life and Metroid achieve this in the same way; they make the player walk into the aftermath of some devastation or some expansive area of recent abandonment. In Half-life the latter comes out through the Black Mesa facility and it’s soulless interiors and hard surfaces, in Half-life 2 the former comes out through the dried out river area which has seen shocking environmental impact. These landscapes are rich in markers that signify emotional impact and allow the player to absorb the full impact of the environment by elongating the moments of low player participation. Half-life 2 in particular achieves this with it’s drawn out environments (again, the dried out water ways of ‘Route Kanal’) which only demand that the player continually drive forward – no Combine soldiers, no antlions – just long stretches of minimalist environment. Both the Metroid and Half-life series excel at these foreplay-esque gameplay sequences which work to intensify the moments when you make first contact with threats.

I personally prefer the way the Metroid games manipulate the player’s emotional state through atmosphere. Of course, each game does this differently.

For instance, Metroid II is a very mute game throughout, each of the confrontations with the 39 Metroids are peaks in excitement, exacerbated by the long stretches of loneliness. Metroid Prime 2 symphonically and in measured frequency of native fauna, controls the game’s atmospheric peaks and dips. The game begin low, peaks, normalizes and then stays constant, occasionally interrupted by confrontations with Space Pirates – rinse and repeat. Overall that constant is much higher, but the peaks are much lower too. Generally speaking, the hills balance out the valleys in either case.

Half-life (both games) on the otherhand never become exciting. The interludes of excitement (usually confrontations with Combine soldiers) rarely feel threatening. There are two reasons for this: the atmosphere and the threat. We can discover how Half-life fails (or is less successful) in this regard by contrasting it with how Metroid succeeds. The Half-life games are (for the most part) void of one critical element that allows the Metroid games to so vividly manipulate atmosphere: sound. The Metroid games use sound – even muteness (which is over exhausted in Half-life) – very effectively. The Half-life games rarely have any background music to set the mood. Occasionally, the music introduces the in-game drama with a crescendo, but not often enough to be considered consistent. The confrontations themselves are (again) mostly unexciting, the dominant selection of enemies are weak fodder, only the Combine foot-soldiers and those evil chimera/licker monsters are exceptions. Even the Combine soldiers are dispersed in limited numbers. This all makes for mostly uneventful gameplay, with no atmospheric crutch.

There are two examples of where the games felt particularly exciting, both which deviate from the aforementioned norms of the main game, concentrating on the aural atmosphere and conflict. The first was in one of the abandoned docks (Half-life 2). Once you make land, a helicopter roars out, the music breaks to one of the game’s few but excellent exhilaration tracks and you’ve got to run-and-gun through a series of freight containers while being attacked from air and land. You then make your way into the compound, clear the area and open the water gates only to be confronted by more guards. The whole sequence plays on the shifting atmosphere, which changes on arrival, switches back once clearing out the guards and changes again once they send reinforcements. It switches between quiet calm and exalted panic wonderfully. In this instance the music and conflict are used collaboratively to shape an enthralling experience.

The second example is Nova Prospekt which I consider the most immerse part of the game. The music is used well throughout, consistently creating an air of atmosphere that accompanies the visual design and layout of the place. The Combine soldiers are a mean threat and the use of antlion baiting and turrets diversify the approaches to conflict. It feels cohesive and is genuinely convincing compared to the relatively tame Ravenholm. Note though, that these two examples are divergences from the bulk of the game.

There are set piece battles and events which bump the excitement up a little, but they’re mostly non-affairs which are over rather quickly (ie. shooting a gunship down with a couple of well placed shots). The two games are like this from start to finish, it’s all foreplay and nothing else. Talk about leaving you hanging.

I’m sure that people would say that this is part of Half-life‘s style, it’s meant to be like that, it contributes to the game’s determinedly realistic approach, but again, it didn’t make for a particularly compelling game. It’s dull, almost nauseatingly vanilla at times.

There are many constituents that form together to make the Half-life series particularly realistic, I enjoy all of these besides the things that contribute to the boredom. I liked the empty environment, the way everything is told in first person, the fact that the game refuses to answer all questions – these are all positive assets. On the other hand I dislike the meager enemy set, lack of rewards for exploration and uneventful gameplay are features that push realism to the point of uninteresting.

First Person Platforming

Most, it not all of the following criticism is leveled exclusively at the original Half-life, the sequel is not immune though.

Considering that all first person shooters since the original Half-life have basically flogged everything that made the original so redefining, I can understand how playing both of these games in a modern context (where Half-life‘s qualities are the norm) probably destroys my appreciation of the games. I suspect that this has also played a large influence over my immersion into the games too, since I’m better acquainted as a player with the techniques Valve would likely pull on me. That is, my awareness of what I’m playing supercedes the desired effects that the developers are trying to have on me through the use of fixed set pieces for narrative – ie. head crab in a vent. The following though can not and will not ever been forgiven.

The platforming is god awful. First person platforming is very difficult to design for and it’s clear that Valve made a huge mess of this, so much so that platforming was barely present in the sequel. The key problem is that the environmental layout wasn’t designed very well to accommodate jumping and tight maneuvers, yet the game constantly demands too much of you and at such a high frequency.

Allow me to garnish with some examples – I need to vent. Two instances come to mind, very vivid. The first is from Half-life, nearing the middle of the game you find a set of stairs leading to a control panel. Two blue trip-wire lasers set to explosives cover the stairs. The first can be easily avoided by crouch walking underneath it, the second one is at step level and must be jumped over. The problem is the slant of the stairs makes it impossible to jump over, Gordon can only hop maybe 20cm, landing on the trip wire. It is possible to make a running jump and successfully bypass the laser, this is very difficult to do since the leeway is incredibly narrow but it’s possible. I achieved this once but unfortunately the game nudge me backwards right into the beam once I landed. P=MV I guess. Eventually I decided that I could reach the top by rubbing up to some boxes to shift them around the room to eventually construct my own makeshift sets of stairs, terribly awkward though.

The second instance, the original Half-life again, occurred when Gordon was on the outside and a tank rolls up, later you make your way into a building, scale the ledge and leap to reach a ladder. The problem is the gap between the ladder and platform is so distant that you’re more than likely to discard the route and head off wandering aimlessly elsewhere. The clipping and detection is awful, finicky at best.

(I really need videos to prove my point)

Progression Clues

One thing you begin to notice while playing Half-life and Half-life 2 is the way the games drops clues to guide you along your way as well as to foster investigation, that is to create player narrative. The environmental layout, use of aesthetics and sound, scripted scenarios are examples of the way Half-life guides the narrative experience of the game. It’s truly a game that marries story and gameplay well.

Driving along on your hovercraft you’ll spot an abandoned house at the corner of your eye, there may be some sort of distinct marking or attribute about the building which will lure you over to discover the aftermath of some event – usually murdered citizens. These areas almost never have any use besides some wayward ammo and health dumps, instead they are designed to create context and they achieve this well.

These devices are all heavily constructed – you were meant to look in that house. The game dictates that as you make your way around the bend, that abandoned house will be right in the corner of the player’s visual frame, and whatever peculiar marking the location has, it’s bound to arise the player’s suspicion. Hence the player will unwilling fall into the designers trap and investigate. It’s genius really.

Two of my recent columns on GameSetWatch have discussed performance management through language, in this case we can see constructed performance through design.

Being a rather dated game, it’s easier to see the strings pulling the player along in the original game. Sometimes they were blindly obvious to the player and prove that the title doesn’t really stand the test of time (more on that later). Half-Life 2 does a much better job at concealing it’s strings, and comes off more convincing.

The con doesn’t always work as effectively as it should and there’s rarely little contingency plan in case it doesn’t. Take for example a sequence nearing the end of Half-life 2. Gordon Freeman and his team of infinitely-spawning civilian friends manage to take down two of the long legged drones with mounted sentries. Once the battle is won it isn’t explicitly clear where to go next as the battle took place on the roof of a building. I spotted one of the civilians firing gunshots into the distance and followed the dead end trail, suspecting that it might steer me in the right direction. After 30 minutes of fluffing about I realized that I had to cross a thin timber framework adjacent to the building where the battle ragged. I would have never suspected that the thin tight walk was actually walkable terrain, moreover it was intended that I would cross it. I fell into these road blocks on frequent occasions for both games – massive headaches ensued.

Vanilla Template + Gimmicks = Success

I’ve developed this fascination with the way games with vanilla templates become interesting through the use functions other than the new abilities gained by the protagonist. Super Mario Bros. 3 or Prince of Persia: Sands of Time are two good examples of games where the protagonist has a fixed, initial skill set and the game world itself is ultimately the catalyst for fun. If either of these games had sucky level design, the games would not be very good – the level design is directly proportional to fun.

Half-life 2 has a vanilla template but instead of using level design to create fun, in employs a consistent use of gimmicks. This includes the two vehicles (the car and hovercraft), the gravity gun (in particular the saw blades in Ravenholm once you acquire the gun), the antlion posse, the citizens who form a squad and lastly the re-engineered gravity gun. Without these tricks, Half-life 2 would be a rather generic shooter.

Design and Emulation Issues

Major criticisms aside, both Half-life games contain a number of small design issues that I quickly want to run through. The first of which might be related to the Steam emulation of the original game, I’m not sure. The original Half-life feels rather finicky and quirky at times – particularly with player movement, clipping and enemy reactions. The worst offender would have to be a glitch I encountered on Xen. I couldn’t defeat the spider boss as it refused to jump down onto the webbed platform allowing me to deliver the coup de grâce, giving entrance to the floor below. After reading about this glitch on GameFAQs and then attempting to jimmy my way around it, I realized that I couldn’t. So I actually couldn’t continue my game – that’s right, I haven’t even finished Half-life. >_<

The second minor quibble relates to ammo and health placements. The combat in Half-life and Half-life 2 is moderate for the most part yet the game can sometimes drown you with supplies before leaving you standard when you most need it. Also the game doesn’t reward exploration besides additional ammo and health packages which often aren’t needed. There’s rarely any benefit in walking off the beaten track besides having to head back on course.

Levels of Appreciation

Lowered the pitchforks and sticks? Oh good. One thing I tried to take into account while playing both these games is that they were very influential for their day, so much so that what they introduced is now standard fair and it’s likely that I would take this for granted in my play throughs. I can’t help that. I’m sure if a gamer of this era went back to play Goldeneye (or any other game for that matter) for the first time then they’d likely be writing the same catalogue of complaints. Still, the merit in sharing this evaluation is worthwhile in assessing the way these games hold up and if they’re worth playing today.

I will be concluding my thoughts on these two games in my next article where I dissect what I perceive to be the series’ most endearing quality; the journey. So stick around till next time, won’t you?

Additional Readings

Eurogamer Xbox Review (good hindsight here)

Retronauts Half-life Podcast (scroll some to find)

An Entree to Half-life Discussion

June 17th, 2009

I’ve recently been intensively playing a number of games which I’m yet to have discussed yet, two of those include Half-life and Half-life 2. I’ve got a bundle of opinions on the series which I’ll get to later. For now though I just thought that I’d text dump this short story from Wikipedia that I found when doing some recent research on the series. I’m sure you’ll find this drama rather interesting if you hadn’t heard of it already.

“Half-Life 2 was merely a rumor until a strong impression at E3 in May 2003 launched it into high levels of hype, where it won several awards for best in show. It had a release date of September 2003, but was delayed. This pushing back of HL2’s release date came in the wake of the cracking of Valve’s internal network,[51] through a null session connection to Tangis which was hosted in Valve’s network and a subsequent upload of an ASP shell, resulting in the leak of the game’s source code and many other files including maps, models and a playable early version of Half-Life Source and Counter-Strike Source in early September 2003.[52] On October 2, 2003, Valve CEO Gabe Newell publicly explained in the HalfLife2.net forums the events that Valve experienced around the time of the leak, and requested users to track down the perpetrators if possible.

In June 2004, Valve Software announced in a press release that the FBI had arrested several people suspected of involvement in the source code leak.[53] Valve claimed the game had been leaked by a German black-hat hacker named Axel Gembe. Gembe later contacted Newell through e-mail (also providing an unreleased document planning the E3 events). Gembe was led into believing that Valve wanted to employ him as an in-house security auditor. He was to be offered a flight to the USA and was to be arrested on arrival by the FBI. When the German government became aware of the plan, Gembe was arrested in Germany instead, and put on trial for the leak as well as other computer crimes in November 2006, such as the creation of Agobot, a highly successful trojan which harvested users’ data.[54][55][56]

At the trial in November 2006 in Germany, Gembe was sentenced to two years’ probation. In imposing the sentence, the judge took into account such factors as Gembe’s difficult childhood and the fact that he was taking steps to improve his situation.[57]”

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99