Wasteland Ventures (Fallout) #5 – 3 Forms of Grind

January 16th, 2011

There I was really digging Fallout’s professional storytelling and engrossing atmosphere when the grinyness of the whole experience dawned on me. Now forget for a minute the collocation of “grind” to JRPGs, because Fallout is nothing of the sort. Rather than being based on mindless repetition, there are three other elements which significantly chaffed up my Fallout experience.

Interface

Managing large amounts of inventory in Fallout is just a complete and utter mess in micro-management due to the forced reliance on the clunky interface by the inventory-limiting strength stat. Let’s start with the equipment screen.

This screen is used for checking stats and equipment items for use. There’s an obvious issue here in that only 6 items are displayed on-screen at the one time and that access to other items requires repeated clicking on the two arrow buttons. This interface quirk is exacerbated by the fact that every new item gained or de-equipped automatically goes to the bottom of the list. The items that you use most frequently are the same items that are constantly equipped and then re-equipped (for instance, switching out guns to accommodate enemy types), so over time the least used items become the most readily available ones and accessing useful items becomes a chore and creates dead space in the gameplay.

This screen is the looting and stealing screen. It is effectively the screen for “free trading”, being stealing, trading with NPC cohorts (which, by design fault, is also stealing) and taking items from interactive window dressing (cupboards, bookcases, tables, etc). The issues here are doubly worse than the prior screen because this time there are two limited displays of inventory, one for either party. Just like with de-equipped items, anything traded automatically goes to the bottom of the heap.

Let’s say that you stumble upon a rare item, but are filled to capacity. The obvious thing to do is to offload excess gear to an NPC to make room in your inventory (space, ie. weight, which is dependent on your strength stat). Keep in mind that the total weight can only be seen the inventory screen (above) and weight of individual items is shown on the same screen after right clicking and selecting observe (this changes the text in the box on the righthand side). Weight is therefore only displayed on this screen. So, you trade away. The rare item that you want is, let’s say, 3kg. You have 1kg of free room in your bag. You trade away one lot of ammo that is 1kg and another that is .75kg, leaving only 2.75kg of space. After making the initial trade with the NPC, you try to pick up the rare item again but you still can’t, your bag is supposedly full (short .25kgs). So, you go back to trade, and trade some more to the NPC, but whatever you try to trade is too large by maybe .30kg. Therefore, you trade the prior items back and start again hoping to match a winning combination. All of your trading is done rather arbitrarily, as it takes exiting a trade and looking through the inventory screen to view the actual weight, and doing this for each item consumes copious amounts of time; that is even if you can hold the items you’re wishing to weigh. Also consider that each time you trade back items, you must scroll to the bottom of the list to find it. Needless to say, trading items when you’re near full capacity is a disaster best avoided.

Maybe the biggest cock-up of them all is the bartering screen. Four sets of scrolling inventory. At least this time there is a value which indicates if the transaction is even possible.

Repair: The simplest form of repair would be to use the white space to the left and right of the interface to display more items. Specifically, the “free trading” screen could display 18 items per character if it used both the outside whitespace and the internal space, granted the avatars for the parties were placed above. And for the bartering screen, there’s an easy fix: don’t waste the above area in the middle of the screen.

Lack of Quick Exit

Watch from 6:28 to end (may wish to mute sound)

In Fallout‘s towns that are spread over several screen transitions (Junktown, The Hub, Necropolis, Brotherhood of Steel and Boneyard), it takes entirely too long to exit one of these areas. On entering each town, players can quick jump to any previously visited area divided by a screen transition via a map, however, no such option can be brought up if they wish to leave. In larger areas like The Hub, this can create 1-2 minutes of pure dead space where the player is simply waiting, unengaged, for their avatar to make it to the other end of the map.

Repair: This problem could be easily sorted with a quick exit option, speeding up the run (not sure how viable this is while still keeping the game realistic), removing large, unneeded chunks of terrain from the maps or adding exits to the main may on every section.

Exploring the Skinner Box

Fallout, as an exploration game, is faced with balancing the realism of the locations and the obligations of exploration. These two elements ought to be considered here. Firstly, each individual player has their own degree of committal to exploration in a given game. Some players choose to leave no rock unturned, other players aren’t honestly all that fussed about leaving areas unchecked. Secondly, in order for many of the environments to be contextually appropriate, they need a fair degree of furnishings. Take, for example, the Brotherhood of Steel stronghold. For this area to be a stronghold, it needs its fair share of rooms, lockers, beds, toilets and so forth. If the stronghold didn’t have enough of these things, then it could hardly be a believable stronghold, now could it? Since the furnishings can all be checked for hidden loot and may contain rare, secret goodies, obsessive explorers are unwittingly baited into mindlessly scanning every part of the environment and so ensues a grind. Now, let’s remember that this is a ramification of using interactive assets as window dressing for environments.

And thus we enter discussion on the whole skinner box debate, which is really a debate about the size and frequency of rewards in game and how it affects play behaviour. Fallout falls on the high frequency, small reward end of the scale, while, my go-to comparison game, Super Metroid, falls closer to the opposite end of the spectrum. In Fallout, players that explore often are rewarded frequently, but only in pint-sized doses. Occasionally, players will stumble on an incredible reward, in turn rationalising the need for these players to explore everywhere. This design obviously fuels an obsessive compulsive approach to play. Fortunately, there aren’t terribly many incredible bounties strewn around the place, so the skinner box effect that I just outlined isn’t all that potent, albeit still present. In Super Metroid the rewards are fewer, but more significant and require more sophisticated play behaviour to obtain (keen observation and problem solving skills).

There’s a separate argument to be had over whether interactive elements of a game which don’t yield any significant contribution to the gameplay ought to be included in the game at all. After all, if they don’t create counterpoint or interplay with the core mechanics then is there really any need for them? Yet if they weren’t there, then would there be all that much credibility to the environment? A solution depends on where you stand on this argument.

Repair: Possible ideas for repair include making all window dressing non-interactive, removing all rewards strewn throughout the window dressing in set areas to indicate that an area is free of rewards (a clear distinction between these areas must be made, otherwise players will be confused and ultimately explore less) or just reducing the size of the areas and therefore reward granting elements.

Each of these solutions has its own issues. Removing all interactivity from window dressing would make the environment feel lifeless. Having fixed areas where exploring the environment yields rewards and other times doesn’t would diminish the player’s trust in the game world and encourage them to abstain from exploring. Reducing the size of each environment would make the game, by appearances, seem less epic.

Conclusion

Fallout’s poorly designed interface for inventory management, the amount of needless walking and compulsiveness to grind for loot all dwell on the overall experience as types of grind. For now, this concludes my writing on Fallout, the Wasteland Ventures continue though as I make my way through Fallout 2. Included in my readings below is discussion on interface grind and pleasantries which may also be of interest.

Other Readings

Iwata Asks – Dragon Quest IX (Dragon Quest & Mario Similarities)

Wasteland Ventures (Fallout) #4 – The Survival Trinity

December 29th, 2010

As the spoilerific video above shows, Fallout can be a ploughed through in under 10 minutes, but those who’ve played Fallout the long and proper way know that getting to the end is not nearly as easy as the video makes it look.

There are three main goals in Fallout: return the water chip to Vault 13, destroy the mutant plague and kill the mutant leader. These goals may seem simple enough, but they’re caught beneath a myriad of layered restrictions which blur the direct course to each solution. These restrictions are pertinent to what I call the survival trinity: intel, combat and inventory; the three subsystems of Fallout’s gameplay and the areas of expertise the player needs to master in order to complete the three goals and beat the game.

Intel

Unlike in JRPGs where a core area (cave, tower, dungeon)-town-core area structure dictates the general level design and progression model, in Fallout, the world map is simply a giant, unmarked black box awaiting you. With such vague goals and a seemingly open world to explore, the player needs to find their own direction and to do that they require the first piece of the trinity, intel. It’s up to the player to brief themselves on the world, as Fallout only offers 2 concessions from the onset: the name of a nearby town (Shady Sands) and a purpose (get the water chip). So, it’s the information that the players themselves must scrounge out that will lead the course of direction, and not a rigid form of forced progression.

(Granted Fallout’s still a primarily linear game, but one which uses a series of more natural, soft constraints which work progressively to limit the player’s access. For example, continually more difficult enemy encounters on the world map and denied access into some townships prevent the player from delving too far ahead).

Once the player finds word of another shanty town through conversing with the locals, that location is marked on their world map screen. The towns themselves are very different to those in JRPGs. A typical JRPG town consists of the following: an inn, a weapons store, an armour store, a magic store and a quest giver. These games even go to the liberty of marking these out for with labels on shop fronts and a clear language of level design. Fallout, sticking to its nuclear apocalypse theme, is much more variable than that. On arriving to a town, the player needs to find out who the big players are and what’s happening. Oftentimes the player cannot even access these quest givers unless they meet certain conditions requiring knowledge gained elsewhere.

In practical terms, communication is a very simple mechanic. Players just click on a character to initiate a conversation. Various dialogue options then appear when appropriate. Depending on what option is selected, various opportunities for using the other mechanics open up (combat for instance). For example, if you agitate an NPC enough through dialogue options, then they will attack you. Increasing the speaking statistics opens up more dialogue options and therefore more interesting possibilities for gameplay (ie. convincing the Khans leader that you are his father). As with life itself, communication is the conduit to greater things.

The majority of Fallout‘s restrictions are intel-based. If the player learns the ins-and-outs of the wasteland through conversation then it’s easy to breeze through, as the speed run video so nicely demonstrates. That is, actually knowing what to do can circumvent the need for combat or specific inventory. As we can see in the speed run video, the other parts of the trinity aren’t necessary in this run of the game. But, because Fallout is so opaque, finding out this information in the first place fills the meaty duration of the game and ultimately requires the use of the other sides of the trinity.

Practical examples of intel and restrictions:

- having places marked on your map

- given more contextual information on the wasteland

- informs the player on where to use what item

Combat

Combat, as the most primal form of defence and survival is fairly self-explanatory. The wasteland is hardly a safe place, so in order to survive the player will often have to fend off danger. While it is technically possible to meet each of the three goals without conflict (again, see the speed run), for most players combat is a large part of post-nuclear-war life. Hostile enemies populate the world map and most important areas, rational characters will turn on the player and even when responsibly dealing with characters who are so obviously corrupt. combat is required as a form of brute force (Gizmo and Kane). Sometimes force is necessary in order for the greater good.

Combat has the most sophisticated system of mechanics, a turn-based system with weapons, armour and inventory governed by action points. Action points are a currency that regenerate every turn and limit the amount of action per each turn.

Practical examples of combat and restrictions:

- defeating guards that block doorways

- trekking deeper into the environment

Inventory

Inventory is the backbone to combat and other systems. Inventory management mechanics, stealing, trading, unlocking and the actual uses of the inventory items. Having the right inventory opens up doors otherwise inaccessible. I will talk more specifically about inventory management in the following post.

Examples:

- Having enough/the right items to trade

- Stealing or looting a collection of wares that can be traded

- Using certain inventory in specific instances. Ie using the radio at the weapons base to send the guards away

Wasteland Ventures (Fallout) #3 – Level Designing For Skills

December 2nd, 2010

In the previous post I wrote up a basic outline for Fallout‘s quests and modelled an example. This time I want to build on some of the additional comments made about the skill system and level design. I want to see how the level design supports player freedom and facilitates interplay for the myriad of potential outcomes the player may take respective of their skillset.

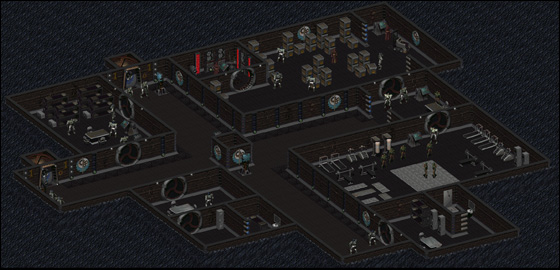

Unfortunately I could only find these teensy weensy map images to work with. Under each image is a link to a larger, blown-up version which may be a bit clearer.

Gizmo’s Casino

Key – Red dots: Guards, Green dot: locked door, 4 – location of Gizmo

Lock Picking (Optional)

Prior to tackling this mission the player can talk to an NPC (I think it was Marcelles from the hotel) who informs the player that a hidden swag of goodies can be found in the room next to Gizmo. Sure enough they’re right. The room is positioned right next to Gizmo which places it off limits while Gizmo is present (otherwise he’ll bust you if you try to open it). Therefore, this piece of intel in conjunction with the position of the room adjacent to Gizmo persuade the player to overthrow Gizmo so that they can gain the supposedly worthwhile loot.

On the other hand, if the player isn’t aware of this fact then the opportunity that arises for the player to lock pick the door upon removing Gizmo can be considered a form of interplay.

Stealing and Dialogue (Folded Level Design)

The player can record Gizmo’s remarks by planting him with a bug using the steal function. If the player is caught trying to bug Gizmo, Izo (Gizmo’s private body guard) and the 2 goons will attack the player (interplay), folding the level design as the player attempts to escape the casino alive. The folding also constitutes the risk/reward factor.

Combat (Customisable Difficulty)

The player can reduce the risk for failing to plant a bug or choosing the wrong dialogue option (both which turn the guards onto the player), attacking the guards in the first area and then luring out the Izo by Gizmo’s door. This strategy breaks down the combat into smaller chunks and can all be done without alerting Gizmo.

Combat #2 (Pockets of Freedom)

The player can attack other customers in the casino without the guards caring (so long as they’re not involved). This can net the player some extra experience.

Raider’s Camp

The goal of this area is to extract Tandi from the Raiders. The players can enter the premise freely so long as they don’t have a weapon holstered. The peaceful option would be to talk to the leader Garl and then complete one of his requests (trading items, cage match). This option doesn’t utilise much of the level design, so my points here will be looking at the more hostile examples of shooting your way in and/or out.

Key: Red: Guards, Blue: Tandi’s cell

Sneaking, Lock picking and Optional Combat (Customisable Difficulty/Skills Usage)

The front of the house is filled with guards. There are henchmen at the door, in the room just behind it and in each of the 4 tents littered outside. If the player has a decent lock picking skill, they can avoid confrontation by entering the house from the front, sneaking into the cell area, lock picking the door to Tandi’s cell, and the sneaking/fleeing out the backdoor. The 4 gang members in the tents can be avoided if the player lock picks the door and dashes past/takes out the two guards by the back exit.

Combat and Lock picking (Customisable Difficulty)

Alternatively, the player can enter from the back, taking out the 2 guards by the locked door, lock picking the cell door and escaping out the back. Since the guards in the central room will be alerted when you take out the two doormen at the back and walk into the cell area to investigate, there is much more combat involved in this option than the former, but still much less than if you barge in through the front.

Combat (Customisable Difficulty)

Another way to scale the difficulty is to kill the henchmen at the back door, flee and then return and re-enter from the back door.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99