Microtransactions: The Inherent Failure Of Natal and Move, and More

April 6th, 2010

Why Natal and Playstation Move will Likely Fail?

I really ought to dedicate more writing space to this topic, but it’s actually a very simple argument.

The reason why the Wii and DS are so successful and why Natal and the Playstation Move will likely fail is entirely software related. Let’s use the Wii and DS as a case study. Technology alone does not sell hardware, software does, software which works in unity with hardware. If there is no good software to give meaning to the hardware, then people will think that the hardware is useless. If there was no Brain Age, Nintendogs, Elite Beat Agents or Zelda: Phantom Hourglass then people would still think that the DS is useless, as they originally did before software proved them wrong. The same is true of the Wii. (Although the Wii is still somewhat draped in cynicism because 3rd parties haven’t stepped up to the plate as they have with the DS).

If it all comes down to the software then what really matters is who is developing games for these things. 1st party-wise Sony’s Eyetoy studio and Microsoft’s weak internal studios (Rare, most likely will constitute the majority of 1st party Natal games for Microsoft) can’t compare to Nintendo’s internal divisions. None of the software demonstrated so far has captured the press in the same way Wii Sports or Brain Training.

On the 3rd party front, if the Wii has had this technology for some years and has a 60+ million install base and is still lacking quality 3rd party games, then I doubt that many 3rd party developers will jump to the technoligcally-similar Playstation Move or the unestablished interface of Natal with an initial install base of zero. The logic behind developing softwae for these system is absent. Furthermore, with a far smaller market to attack, the developers that do succeed will initially struggle to make significant gains. It will take several developers producing several killer applications for these accessories to gain sufficient momentum and remain relevant. Keep in mind that several of the major publishers backing Natal-developed games are already claiming that they’ll only be developing smaller, mass market titles, hardly the type of product which will sell on a system with a shooter-centric image.

Software aside, how do we know that the hardware itself will work? There are still doubts over the lag in Natal and processing power required to handle Natal games. The Playstation Move only allows for 2 player games. Will these peripherals be bundled with game system or games? The systems themselves are already more expensive than the Wii, add in an accessory and pack-in game and that price naturally increases. Above all else, assuming that Microsoft, Sony or their 3rd parties produce fantastic games, the tech works fine and is affordable and retails support the devices, will they be able to market the peripherals effectively? This, is perhaps as challenging as the development of software. How to unlock an audience you’ve never been successful at capture?

It would be quite the monumental feat for either company to successfully meet these all these challenges, so I figure that their chances are pretty slim. The comparison to Nintendo’s phenomenal success is a bit harsh, true, yet similar levels of success, I’d wager, are needed to establish these devices in the market place and keep them going, particularly with competition from two other companies.

In the end I’m just explicating on what everyone already knows “these things will flop without software”.

Judging the Inherent Fun in Controllability

There’s a sort of mental litmus test which I use to evaluate the controllability in games. It’s very simple, and goes something like this: if all the player could do was control the protagonist in an empty space with no distractions, how long would they play for? That is, to what extent is controlling the character fun on its own?

It’s a bit tricky to judge ultimately, because some games feature much more complicated control systems than others, meaning that it’d take longer for someone to exploit one system to its fullest than others, which may in fact be more enjoyable.

For example, Metal Gear Solid 4 and Super Mario Bros. Super Mario Bros is obviously the superior title in terms of controllability, however, I could fiddle around with all of Solid Snake’s ability set for maybe up to a quarter of an hour.

In anycase, it’s worth considering this methodology, because I’ve personally found it quite useful.

Gamers Don’t Want Innovation

Gamers aren’t genuinely interested in innovation, I’d argue. Put simply, human nature says that we’re afraid/dismissive of truly new ideas. This is the reason why we all remain as slaves to capitalism whilst socialist ideology is cast-typed as extremist/fundamentalist. It’s the same reason why the Wii is still subordinated by the hardcore and the enthusiast, despite delivering innovation.

Innovation is only acceptable in small, familiar doses (subversion of the very definition of innovation), such as Borderlands, which recycles two very familiar forms of play. If games truly embraced innovation then the independent scene would reign over the mainstream.

GameFAQ Writers VS Bloggers: The Better Candidate for Criticism

This year I’ve found myself falling into this habit where on completing a game, I’ll snuff out a guide on GameFAQs to acquaint myself with the bonus material and unlocks that I’m probably missing out on. This habit has made me realise that FAQ writers, as expert players, are in the most advantageous position to effectively evaluate game design, leagues ahead of us bloggers.

Expert players, or at least competitive players seek to win, and win effectively. In order to win they must first fully understand the conditions of the ‘win’ state, ie. the operations of play, and then devise the most efficient means to reach these conditions. Seeing past the glossy veneer and interpreting the game as a series of rules is pivotal to their success. The more familiar they are to these rules, the easier it will be for them to reach the ‘win’ state. While ordinary players also go through these processes as well, it’s almost entirely subconscious (this is why we have difficulty in understanding and talking about games). The mind of a competitive player is always working to sharpen their understanding of the rules.

As a result of all this, when it comes to critiquing games, generally speaking, I think hardened players will be at an advantage. Of course, this is all generalities and what I’m really saying is that being competitive spurs people on to think hard about the operations of a game. This doesn’t mean that non-competitive players are bad evaluators. No. These players don’t need to be competitive in order to think hard about games, but rather, being competitive often helps people to really focus in on game design and that when it comes to general conversation about games, competitive players are likely to be the more interesting conversationalists.

Chess or the Mona Lisa – Games as Art

April 3rd, 2010

[This is the first–and most likely last–time that I’ve weighed in on the games as art debate. As with the R 18+ classification issue, the conversation is largely uneventful and uninteresting, so please enjoy my attempt at a no-nonsense approach to this trivial argument.]

The games as art debate hinges on what we believe games should aspire to be: the Mona Lisa or Chess?

The point of contention is that, fundamentally, video games are chess, but with rich enough contexts to border the medium against others which classify as art. The problem is therefore one of definition. Do we grade art on the construction of rule systems or on the contextual and thematic elements?

The answer is obvious; we grade art on the contextual.

Art has always been graded on themes and emotion, which is why chess, even as a perfect piece of game design, doesn’t count as art. In this regard, Super Mario Bros, Doom II or Resident Evil 4 also cannot be considered as art. If chess can’t do it and, lest we forget, chess has been around for hundreds of years, then Super Mario Bros. has no chance either.

So then, under the traditional evaluation of art, any game which triggers an emotion or displays a sense of beauty is art, even if the “game” part (that is, rule system) itself is completely rubbish. The rules don’t really mean as much, so long as there is an expression of creative talent.

I know what you’re thinking “what a load of bullocks!”. Don’t blame me, blame the definition.

A Change in Definition

I believe that video games will spur a change in the definition of art. The “art” side of video games (the contextual; the side which will first be regarded as displaying “creativity” and emotion) will only continue to refine itself and so long as this art is tied to rules, which it will always be, a re-evaluation must occur. Games will become so artistic in the traditional sense, that someone will have to decide what to do about all those rules attached to the supposed art.

Right here is where I think games will be accepted as art. That is, the rule systems attached to the “art” part will be accepted as an important part of the art itself. I imagine that the acceptance of engineering into the art fold will slowly see the definition come to accept beautifully designed rule systems, such as our old friend Chess, as works of art too.

False Idols

As a rationalist interested in the pragmatic side of games (as opposed to the majority of “games criticism” which is mainly fluff), I think that there are huge problems with our current perception of games as art.

It’s all class-based semantics. Art, as with the word culture, has been misused as a denotation of high culture. Those of higher class observe art, while those of lower class play games. Even though Chess’ influence is far stronger and wide reaching than the Mona Lisa’s, Chess is still a game for commoners and is therefore not art. Video games, first typecasted for children and now a part of the low cultural ghetto (hello comics!), are destined to be marginalised because of this stupid word “art”. That is, unless we push for a change in meaning and a breakdown of traditional power structures.

Unfortunately, I don’t think this will ever happen, or at least it could happen, at a snails pace, as games such as Bioshock, Flower and Okami are waved around as the banner titles of video game art. These titles are given a high stature because they intend to construct experience which elicit an emotional response in the traditional sense. And there’s nothing wrong with that, particularly under this new-found interpretation of art which I’ve suggested, where contextually and mechanically beautiful media can co-exist. But it is equally important, if not more so, that we promote Super Mario Bros, Super Metroid, Doom II and Resident Evil 4 as works of art also. If we are to truly shift the perception of this medium we need to attack old perceptions tied to class, with new ideas based on design.

In concluding, I believe that we ought to focus on games as an emerging form of art and not games as conforming to the traditional sense of art. In which case we must crown our idols carefully and promote design as integral to our cause.

The Ideological Framework of Berserk

March 30th, 2010

Berserk is an anime adaption of the popular manga series of the same name created by Kentaro Miura. Berserk (anime) covers the first 13 volumes, also known as the Golden Age arc.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1JnCNW-n8FI

Berserk is quite the slow burn, taking its time to establish the underlying themes through the mining of the two main protagonists, Guts and Griffith. Their actions are very important as they symbolise philosophies of human nature (diplomacy and war), forming the ideological centrepiece for the series. As the viewer comes to realise this dichotomy, similarly to the way Guts comes to draw comparisons between himself and Griffith, the initial slow burn soon wears off and Berserk starts to become engrossing.

Guts is a typical brute with a large sword and a short temper who stumbles upon a camp for the mercenary band, the Band of the Hawk, leading to a short feud where Guts is bested by the leader, Griffith. Rather than kill the obstinate young warrior, Griffith offers Guts a deal to join his mercenary band in exchange for his life. Guts unwillingly accepts the offer along with his loss of the battle.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qD2Lumx92Fs

Guts is immediately promoted to the Band of the Hawk’s second in command and becomes curious of Griffith who has unwavering faith in Guts’ abilities. Griffith is an idol within the camp and very much evangelised for his brilliant tactical and combat skills which constantly lead the mercenary group to success. Griffith’s diplomatic treatment of Guts causes some minor jealously within the camp, particularly with the only female member, Casca, who feels a strong personal bond with Griffith. The ensuing conflict derived from the jealousy causes Guts to evaluate the himself against Griffith.

The two men are polar opposites. Griffith is slender with long, pure white hair, wields a thin rapier, speaks with a calm, soft voice and has seemingly no character flaws. He is the embodiment of diplomacy, charisma and camaraderie. Guts has never experienced the level of friendship shown within the group, he doesn’t understand how Griffith is so patient and accepting of others. The only thing Guts knows is the display of strength through combat, he’s the embodiment of war, internalising his emotions and talking only with his blade.

Guts warms to Griffith’s outlook and adopts many of his interpersonal philosophies which allows Guts to integrate within the group. Griffith is immediately close with Guts, often talking with Guts in private about his personal thoughts and endeavours. Such information was never made privy to the anyone else before Guts’ arrival, further fueling the aforementioned jealousy. These sequences of dialogue provide Guts (and the viewer) with food to chew on regarding the underlying thematic elements. The open expression of warmth given towards Guts turns him into another of Griffith’s admirers. However, this idol is also one with an undercurrent of suspicion and here enters the themes of the series’ second half, man’s pursuit of his dreams.

Griffith makes clear to Guts his dream of becoming a king, despite his role as a commoner. He sees this goal as a matter of inevitability and holds a solitary faith towards this pursuit. And the more Griffith divulges to Guts, the clearer the situation becomes.

As the Band of the Hawk continue to rise in reputation, eventually working for and then integrating with the army of Midland, Griffith’s desires become realised. Through the groups transition into royalty figure, Guts notes Griffiths’s burgeoning desire and slowly the two roles change as Griffith’s dogmatic pursuit begins to involve the murder of significant figures of royalty. Guts assists in these assassinations with faith, but slowly coming to question his master’s authority as it becomes increasingly felonious and risky and puts Guts in a position of liability. Griffith’s goals come to create a rift in the ideological framework as Guts, with their positions somewhat exchanged, is now tested by a wavering master.

— Interlude —

Up to this point, Berserk is effective at putting the viewer in a Japanese mindset (I am partly assuming the Japanese here, either way, I mean to say an environment where social actions have far greater consequence). In many regards, Berserk pulls you in, because it places you in the mindset of Guts and then uses Griffith to spark your interest. Like Guts, I found myself becoming curious of Griffiths’s behaviour and wondering whether his intents where disingenuous, whether he was a false idol, what exactly their representative attitudes mean and whether they could be considered absolute (in which they’re not).

—-

As Griffith is drawn closer to his goals, Berserk‘s grip tightens as you can see the balance tipping away from Griffith and the veneer about to come off. Up to this point, Griffith is faultless, everything he touches turns into gold which makes the climax very important. Guts acts as the tipping point to the shift in roles, being the first to see the strings from that has been presented to the viewer. Clearly a warrior of great might, Guts understands that he is playing to the desires of another man and not his own. He fights causality by deciding to leave the Band of the Hawks without explanation. Even though Griffith could be seen as manipulative, his manipulation is also to the benefit of his fellow soldiers, so I do not think that Guts sees him as a false idol. It seems that Guts wishes to simply walk his own path, rather than be further involved with Griffith’s personal bidding. Here we see the series folding its narrative over as Griffith, now the representation of war, challenges Guts to a duel before he leaves–the result again deciding Guts’ fate. As had occurred before, the diplomatic warrior wins; Guts cuts Griffith’s rapier in half in the process.

Griffith, clearly wrought by his defeat and the worry of the absence of his right-hand man (for whom he can control), enters the princess’ chambers that night and proceeds to rape her. A servant spies a glance and then reports directly to the king who surrounds Griffith with guards, and without his sword, Griffith submits to the bottom floor of the castle’s prison. The Band of the Hawk are removed shortly thereafter.

These last 2 DVDs (in the 6 DVD set) represent a sudden change in the series. There’s a short lull period after the disbanding where Guts goes off and trains in the woods, before running into a reunited Band of the Hawk lead by Casca. Guts aids in defending the group from a rival mercenary band and is then convinced to stay after seeing Casca in a state of exhaustion and despair. Guts, as the new commander, then helps the crew invade Midland castle and rescue their former leader. Again, we see Guts assume the role Griffith had at the beginning of the series and the quest start anew.

Guts, Casca and several other prominent members of the group reclaim Griffith from his cell who is severely malnourished and frail beyond repair. He’s a cabbage who hardly has the energy to speak, yet in regards to roles, Griffith is the arrogant, young version of Guts seen at the start of the series. Griffith notices the new-found, loving relationship formed between Guts and Casca in his time of absence and in jealously commandeers a cart which sends him careering into a lake. In the lake, Griffith is reunited with the Crimson Behelit, a red stone that he always wore around his neck. He uses the Crimson Behelit to summon several demon gods, whom he offers the Band of the Hawk as a sacrifice to immortalise him as a God, fulfilling his dream.

Although I don’t agree with the ending and in fact find it at odds with the rest of the series (however much it is authentic to the manga), it does show the root of Griffith’s desires and the extent at which he is willing to go in pursuit of his dream. This ending shows us that our desires can corrupt even the seemingly invincible of all men, as Griffith transforms himself from an angel-like figure into a demonic force, both literally and figuratively.

In my opinion, Berserk would have been a better series if it had cut the first and final few episodes, closing after Griffith was imprisoned and Guts had left the Band of the Hawk. (The first episode is of the events after the Golden Age story arc and does not fit in with the events of the rest of the series). As we can see from this article, in regards to the underlying ideologies at play, it would have been smarter for the series to have been cut earlier, concluding with the narrative coming of full circle. In any case, Berserk’s two main characters teach us much about human nature, diplomacy and war, causality and the way in which our endeavours can separate us from our friends and allies.

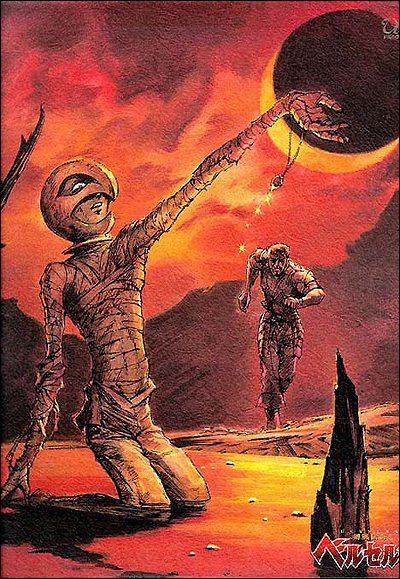

Images from Berserk Chronicles Image Gallery

Additional Readings

Young Animal Overview of Manga volumes

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99