The Ideological Framework of Berserk

March 30th, 2010

Berserk is an anime adaption of the popular manga series of the same name created by Kentaro Miura. Berserk (anime) covers the first 13 volumes, also known as the Golden Age arc.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1JnCNW-n8FI

Berserk is quite the slow burn, taking its time to establish the underlying themes through the mining of the two main protagonists, Guts and Griffith. Their actions are very important as they symbolise philosophies of human nature (diplomacy and war), forming the ideological centrepiece for the series. As the viewer comes to realise this dichotomy, similarly to the way Guts comes to draw comparisons between himself and Griffith, the initial slow burn soon wears off and Berserk starts to become engrossing.

Guts is a typical brute with a large sword and a short temper who stumbles upon a camp for the mercenary band, the Band of the Hawk, leading to a short feud where Guts is bested by the leader, Griffith. Rather than kill the obstinate young warrior, Griffith offers Guts a deal to join his mercenary band in exchange for his life. Guts unwillingly accepts the offer along with his loss of the battle.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qD2Lumx92Fs

Guts is immediately promoted to the Band of the Hawk’s second in command and becomes curious of Griffith who has unwavering faith in Guts’ abilities. Griffith is an idol within the camp and very much evangelised for his brilliant tactical and combat skills which constantly lead the mercenary group to success. Griffith’s diplomatic treatment of Guts causes some minor jealously within the camp, particularly with the only female member, Casca, who feels a strong personal bond with Griffith. The ensuing conflict derived from the jealousy causes Guts to evaluate the himself against Griffith.

The two men are polar opposites. Griffith is slender with long, pure white hair, wields a thin rapier, speaks with a calm, soft voice and has seemingly no character flaws. He is the embodiment of diplomacy, charisma and camaraderie. Guts has never experienced the level of friendship shown within the group, he doesn’t understand how Griffith is so patient and accepting of others. The only thing Guts knows is the display of strength through combat, he’s the embodiment of war, internalising his emotions and talking only with his blade.

Guts warms to Griffith’s outlook and adopts many of his interpersonal philosophies which allows Guts to integrate within the group. Griffith is immediately close with Guts, often talking with Guts in private about his personal thoughts and endeavours. Such information was never made privy to the anyone else before Guts’ arrival, further fueling the aforementioned jealousy. These sequences of dialogue provide Guts (and the viewer) with food to chew on regarding the underlying thematic elements. The open expression of warmth given towards Guts turns him into another of Griffith’s admirers. However, this idol is also one with an undercurrent of suspicion and here enters the themes of the series’ second half, man’s pursuit of his dreams.

Griffith makes clear to Guts his dream of becoming a king, despite his role as a commoner. He sees this goal as a matter of inevitability and holds a solitary faith towards this pursuit. And the more Griffith divulges to Guts, the clearer the situation becomes.

As the Band of the Hawk continue to rise in reputation, eventually working for and then integrating with the army of Midland, Griffith’s desires become realised. Through the groups transition into royalty figure, Guts notes Griffiths’s burgeoning desire and slowly the two roles change as Griffith’s dogmatic pursuit begins to involve the murder of significant figures of royalty. Guts assists in these assassinations with faith, but slowly coming to question his master’s authority as it becomes increasingly felonious and risky and puts Guts in a position of liability. Griffith’s goals come to create a rift in the ideological framework as Guts, with their positions somewhat exchanged, is now tested by a wavering master.

— Interlude —

Up to this point, Berserk is effective at putting the viewer in a Japanese mindset (I am partly assuming the Japanese here, either way, I mean to say an environment where social actions have far greater consequence). In many regards, Berserk pulls you in, because it places you in the mindset of Guts and then uses Griffith to spark your interest. Like Guts, I found myself becoming curious of Griffiths’s behaviour and wondering whether his intents where disingenuous, whether he was a false idol, what exactly their representative attitudes mean and whether they could be considered absolute (in which they’re not).

—-

As Griffith is drawn closer to his goals, Berserk‘s grip tightens as you can see the balance tipping away from Griffith and the veneer about to come off. Up to this point, Griffith is faultless, everything he touches turns into gold which makes the climax very important. Guts acts as the tipping point to the shift in roles, being the first to see the strings from that has been presented to the viewer. Clearly a warrior of great might, Guts understands that he is playing to the desires of another man and not his own. He fights causality by deciding to leave the Band of the Hawks without explanation. Even though Griffith could be seen as manipulative, his manipulation is also to the benefit of his fellow soldiers, so I do not think that Guts sees him as a false idol. It seems that Guts wishes to simply walk his own path, rather than be further involved with Griffith’s personal bidding. Here we see the series folding its narrative over as Griffith, now the representation of war, challenges Guts to a duel before he leaves–the result again deciding Guts’ fate. As had occurred before, the diplomatic warrior wins; Guts cuts Griffith’s rapier in half in the process.

Griffith, clearly wrought by his defeat and the worry of the absence of his right-hand man (for whom he can control), enters the princess’ chambers that night and proceeds to rape her. A servant spies a glance and then reports directly to the king who surrounds Griffith with guards, and without his sword, Griffith submits to the bottom floor of the castle’s prison. The Band of the Hawk are removed shortly thereafter.

These last 2 DVDs (in the 6 DVD set) represent a sudden change in the series. There’s a short lull period after the disbanding where Guts goes off and trains in the woods, before running into a reunited Band of the Hawk lead by Casca. Guts aids in defending the group from a rival mercenary band and is then convinced to stay after seeing Casca in a state of exhaustion and despair. Guts, as the new commander, then helps the crew invade Midland castle and rescue their former leader. Again, we see Guts assume the role Griffith had at the beginning of the series and the quest start anew.

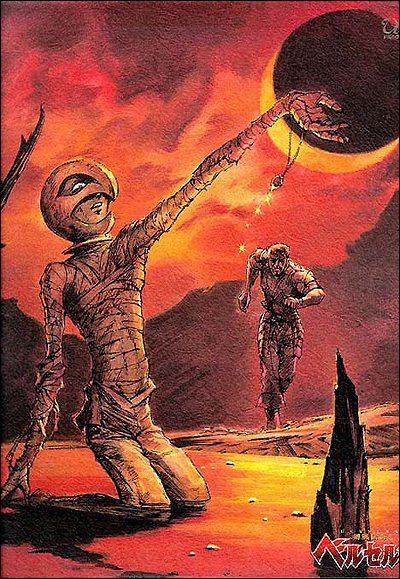

Guts, Casca and several other prominent members of the group reclaim Griffith from his cell who is severely malnourished and frail beyond repair. He’s a cabbage who hardly has the energy to speak, yet in regards to roles, Griffith is the arrogant, young version of Guts seen at the start of the series. Griffith notices the new-found, loving relationship formed between Guts and Casca in his time of absence and in jealously commandeers a cart which sends him careering into a lake. In the lake, Griffith is reunited with the Crimson Behelit, a red stone that he always wore around his neck. He uses the Crimson Behelit to summon several demon gods, whom he offers the Band of the Hawk as a sacrifice to immortalise him as a God, fulfilling his dream.

Although I don’t agree with the ending and in fact find it at odds with the rest of the series (however much it is authentic to the manga), it does show the root of Griffith’s desires and the extent at which he is willing to go in pursuit of his dream. This ending shows us that our desires can corrupt even the seemingly invincible of all men, as Griffith transforms himself from an angel-like figure into a demonic force, both literally and figuratively.

In my opinion, Berserk would have been a better series if it had cut the first and final few episodes, closing after Griffith was imprisoned and Guts had left the Band of the Hawk. (The first episode is of the events after the Golden Age story arc and does not fit in with the events of the rest of the series). As we can see from this article, in regards to the underlying ideologies at play, it would have been smarter for the series to have been cut earlier, concluding with the narrative coming of full circle. In any case, Berserk’s two main characters teach us much about human nature, diplomacy and war, causality and the way in which our endeavours can separate us from our friends and allies.

Images from Berserk Chronicles Image Gallery

Additional Readings

Young Animal Overview of Manga volumes

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99