Microtransactions: Breaking Stuff

April 24th, 2013

Breaking the News-Previews-Reviews Trinity

Thanks to the likes of Polygon and the collective efforts of Simon Parkin (I’m generalising, obviously, but these are two key examples), games journalism has made great strides over the past few years and “features” are now a significant part of most games press websites. Still, though, the uptake to long-form writing on a single game has been slow to say the least. Game-specific discussion pieces free writers from the cover-everything nature of reviews, allowing them to develop a voice and a style, assets which most games sites lack. I guess it’s up to bloggers like us to carry the torch for long-form games discussion.

Breaking the Tyranny that Publishers have over Players and Criticism

This paragraph was originally part of the preface to Rethinking Games Criticism: An Analysis of Wario Land 4.

Publishers are the dictators of the video games industry. Through trailers, controlled previews, planned leaks, media events, early access to review code, and “game journalists” who deliver PR straight from the horse’s mouth without scrutiny, publishers fuel the hype machine which sets the tone for the initial 4 months of a game’s release. The anticipation builds a near impenetrable wall of positive assumption of a games quality pre-release, which the majority of game reviewers do little to challenge. They either get caught up in it or just can’t overcome it individually—given their audience comes into a review expecting their opinions, shaped by the marketing, to be validated. This system, prolonged by DLC, traps players in a self-fulfilling cycle of purchases, which ensures continual cash flow for publishers. To discuss a game well past irrelevancy, like Wario Land 4, is therefore an act of rebellion, a move to show players an alternative to drip-fed corporate capitalism.

Freedom Vs Control

Freedom is an impenetrable beast. The positive associations of the word and the dominance of the American ideology, which ensures that said associations are always upheld, make it hard for someone to vouch for authorial control, but that’s what I’d like to do today. Freedom—as in absolute freedom, the kind that this heading is most concerned with—is destructive. You give too much freedom to a society and people will eat and rape each other. You give too much freedom to the markets and the financial institutions will rob the people of democracy. You give too much freedom to a player and they’ll choose the path of least resistance, thereby bypassing the education needed to develop their mastery of the game. Whether it be an open world game with a world so large that the designers can’t bend the landscape narrowly enough to ensure the player’s rigorously tested on the game mechanics or a strategy RPG where the player can customise their party to the point that they don’t have to play strategically, freedom can be a corrosive force in game design. Players, like students, need the guidance of a teacher before they can be let loose on their own. The more I think about, the more I believe restricted-to-freer practice is the only way to go when it comes to offering freedom in games. It seems that I haven’t finished with this idea just yet.

Microtransactions: With a Vengence

April 18th, 2013

About 4 years ago, I started a semi-regular series of articles called Microtransactions. In these posts, I’d compile comments that were too long for Twitter, but not long enough to warrant their own article. Given that I’ve built up a few notes over the past 2 years of writing this Wario Land book, and not all of them can amount to their own post, I figure that it’s time for me to resurrect this long-forgotten series.

Cooperatives in the Business Side of the Trigon Theory

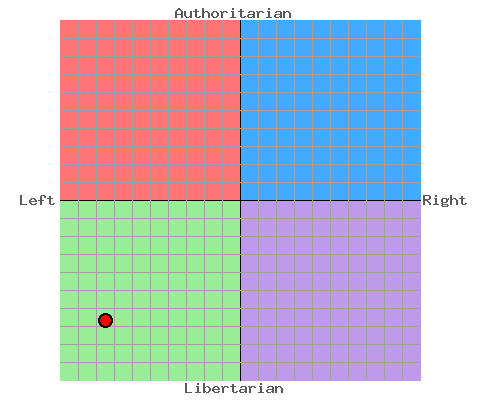

As a democratic socialist, I’m big on cooperative enterprises. When the people who make or use the services or products of a business own the business (ie. democratic ownership), instead of working to maximise profit for shareholders, like most current, privately-owned businesses, the company works for its members and the betterment of its services or products. Richard Terrell’s trigon theory of games, which you can read about here or listen about here, assumes that business’s only interest is to maximise profit for shareholders. I’m curious then, if video game companies were owned by their developers or fan base, how would that change the theory. I’d say that it’d significantly weaken the influence that business has over games (as for cooperatives, profit is necessary to survive, but it’s not the core part of their business) while strengthening the art side (as the workers would be freed from the tyranny of concentrated power at the top).

Information as Cultural Capital

About a month ago, my partner asked me to watch an episode of Miranda with her. Miranda is a UK comedy show about a middle-aged lady, Miranda, and her friends running into all sorts of self-deprecating scenarios. I didn’t think much of the show, I don’t care much for TV, but the comedy reminded me of a growing trend that I’ve noticed.

Many of the jokes in Miranda are based on the clique language Miranda and her friends use within their tight-knit circle. In many instances, it’s as though they try to make a “thing” or a “scene” out of nothing, with pop culture associations as their tool of choice. This form of comedy, I feel, is indicative of the nature of information in this current age. Information is no longer something that you know and can learn from, it’s now a fashion, a form of cultural capital. If you know something about something then you have enough capital to pretend to others that you belong to a particular membership group, which can make one appear cultured or sophisticated. It’s kind of like hipster culture, but with words replacing dress.

Social media has certainly made this way of thinking increasingly more prevalent. These networks operate on two foundations: following others (cultural membership/tribalism) and knowledge as capital (short bursts of text being the primary unit of exchange). A lot of what goes on in social media, whether people like it or not, is the use of information to define one’s brand/place their brand amongst brands which are advantageous to them. Knowledge is often used as a commodity. The contents aren’t important. What’s important is what underlying assumptions come from the information. This is exactly what Miranda and friends do when they make up silly catch phrases and nonsense words. What they say isn’t important. What’s important is that what’s said has a certain fashion which creates comical associations.

Microtransactions: The Inherent Failure Of Natal and Move, and More

April 6th, 2010

Why Natal and Playstation Move will Likely Fail?

I really ought to dedicate more writing space to this topic, but it’s actually a very simple argument.

The reason why the Wii and DS are so successful and why Natal and the Playstation Move will likely fail is entirely software related. Let’s use the Wii and DS as a case study. Technology alone does not sell hardware, software does, software which works in unity with hardware. If there is no good software to give meaning to the hardware, then people will think that the hardware is useless. If there was no Brain Age, Nintendogs, Elite Beat Agents or Zelda: Phantom Hourglass then people would still think that the DS is useless, as they originally did before software proved them wrong. The same is true of the Wii. (Although the Wii is still somewhat draped in cynicism because 3rd parties haven’t stepped up to the plate as they have with the DS).

If it all comes down to the software then what really matters is who is developing games for these things. 1st party-wise Sony’s Eyetoy studio and Microsoft’s weak internal studios (Rare, most likely will constitute the majority of 1st party Natal games for Microsoft) can’t compare to Nintendo’s internal divisions. None of the software demonstrated so far has captured the press in the same way Wii Sports or Brain Training.

On the 3rd party front, if the Wii has had this technology for some years and has a 60+ million install base and is still lacking quality 3rd party games, then I doubt that many 3rd party developers will jump to the technoligcally-similar Playstation Move or the unestablished interface of Natal with an initial install base of zero. The logic behind developing softwae for these system is absent. Furthermore, with a far smaller market to attack, the developers that do succeed will initially struggle to make significant gains. It will take several developers producing several killer applications for these accessories to gain sufficient momentum and remain relevant. Keep in mind that several of the major publishers backing Natal-developed games are already claiming that they’ll only be developing smaller, mass market titles, hardly the type of product which will sell on a system with a shooter-centric image.

Software aside, how do we know that the hardware itself will work? There are still doubts over the lag in Natal and processing power required to handle Natal games. The Playstation Move only allows for 2 player games. Will these peripherals be bundled with game system or games? The systems themselves are already more expensive than the Wii, add in an accessory and pack-in game and that price naturally increases. Above all else, assuming that Microsoft, Sony or their 3rd parties produce fantastic games, the tech works fine and is affordable and retails support the devices, will they be able to market the peripherals effectively? This, is perhaps as challenging as the development of software. How to unlock an audience you’ve never been successful at capture?

It would be quite the monumental feat for either company to successfully meet these all these challenges, so I figure that their chances are pretty slim. The comparison to Nintendo’s phenomenal success is a bit harsh, true, yet similar levels of success, I’d wager, are needed to establish these devices in the market place and keep them going, particularly with competition from two other companies.

In the end I’m just explicating on what everyone already knows “these things will flop without software”.

Judging the Inherent Fun in Controllability

There’s a sort of mental litmus test which I use to evaluate the controllability in games. It’s very simple, and goes something like this: if all the player could do was control the protagonist in an empty space with no distractions, how long would they play for? That is, to what extent is controlling the character fun on its own?

It’s a bit tricky to judge ultimately, because some games feature much more complicated control systems than others, meaning that it’d take longer for someone to exploit one system to its fullest than others, which may in fact be more enjoyable.

For example, Metal Gear Solid 4 and Super Mario Bros. Super Mario Bros is obviously the superior title in terms of controllability, however, I could fiddle around with all of Solid Snake’s ability set for maybe up to a quarter of an hour.

In anycase, it’s worth considering this methodology, because I’ve personally found it quite useful.

Gamers Don’t Want Innovation

Gamers aren’t genuinely interested in innovation, I’d argue. Put simply, human nature says that we’re afraid/dismissive of truly new ideas. This is the reason why we all remain as slaves to capitalism whilst socialist ideology is cast-typed as extremist/fundamentalist. It’s the same reason why the Wii is still subordinated by the hardcore and the enthusiast, despite delivering innovation.

Innovation is only acceptable in small, familiar doses (subversion of the very definition of innovation), such as Borderlands, which recycles two very familiar forms of play. If games truly embraced innovation then the independent scene would reign over the mainstream.

GameFAQ Writers VS Bloggers: The Better Candidate for Criticism

This year I’ve found myself falling into this habit where on completing a game, I’ll snuff out a guide on GameFAQs to acquaint myself with the bonus material and unlocks that I’m probably missing out on. This habit has made me realise that FAQ writers, as expert players, are in the most advantageous position to effectively evaluate game design, leagues ahead of us bloggers.

Expert players, or at least competitive players seek to win, and win effectively. In order to win they must first fully understand the conditions of the ‘win’ state, ie. the operations of play, and then devise the most efficient means to reach these conditions. Seeing past the glossy veneer and interpreting the game as a series of rules is pivotal to their success. The more familiar they are to these rules, the easier it will be for them to reach the ‘win’ state. While ordinary players also go through these processes as well, it’s almost entirely subconscious (this is why we have difficulty in understanding and talking about games). The mind of a competitive player is always working to sharpen their understanding of the rules.

As a result of all this, when it comes to critiquing games, generally speaking, I think hardened players will be at an advantage. Of course, this is all generalities and what I’m really saying is that being competitive spurs people on to think hard about the operations of a game. This doesn’t mean that non-competitive players are bad evaluators. No. These players don’t need to be competitive in order to think hard about games, but rather, being competitive often helps people to really focus in on game design and that when it comes to general conversation about games, competitive players are likely to be the more interesting conversationalists.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99