Wasteland Ventures (Fallout) #1 – Tutorial and Beginnings

October 22nd, 2010

On to the wasteland. I’ll return to the review the comments made in the previous article once I’ve completed Fallout. In the meantime though, I’d like to analyse Fallout on the grounds of freedom of expression and interplay alongside with my regular “ooh, this looks interesting” commentaries. Freedom of expression speaks for itself, interplay though requires an explanation and fortunately I’ve taken one from Richard Terrell, who coined the term:

“Interplay is the back and forth encouragement of player mechanics between any two elements in a game. Put simply, interplay is where actions and elements in a game aren’t means to an end, but fluid opportunities that invite the player to play around with the changing situation.

The easiest way to think of interplay is offensively/defensively or in counters. Consider two elements of a hypothetical action/fighting game. The first element is the player’s character, and the second is an enemy. If an enemy can attack you, does this attack/enemy have a way to be countered? What happens when you counter the enemy’s move? Does the enemy die, does it reset itself, or does the situation change? If the situation changes, is the enemy still a threat? If so, can you counter the new threat? And the cycle repeats.”

My ideas will be presented in a journal format. This first entry will cover the tutorial parts of the game Vault 13-Kahn raiders camp.

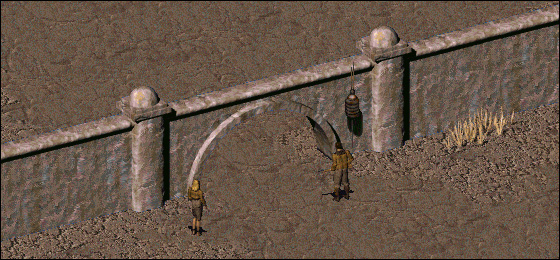

Vault 13

I can’t honestly say that I enjoyed my first few attempts at playing Fallout which is steeped in needless trial and error and some arbitrary stat abstraction.

Your journey begins with the player “rolling” their own character. With wariness of a supposed difficulty spike early on in what is meant to be an already difficult game, I consulted a FAQ and maxed out the most useful stats while minimising the useless ones (known as min-maxing). Useless, or rather relatively less useful, statistics include endurance, outdoors man and luck. The FAQ I used also listed some variables that I shouldn’t raise as I could do so later through books. All very complicated and not so balanced. Fallout penalises players who don’t choose, and then subsequently boost, the appropriate statistics from the outset. It’s quite hard for players to get the gist of the usefulness of certain statistics from the brief descriptions from the menu alone, so rolling your own character has many unnecessary hazards. Fortunately, players can choose a pre-rolled character.

After rolling your character, you leave your isolated home of Vault 13 to a gloomy cave. The introduction to Fallout doesn’t offer any real tutorial on the functions of the game which leaves the player to figure the game out for itself. Fortunately, the cave acts as a fail-safe playground to practice the primary mechanics, despite the fact that they are never introduced to the player. The cave is inhabited by rats which initiate the use of the turn based combat system based on action points and allow for a little practice and experimentation.

Fallout requires some kind of peripheral reading to substitute the lack of tutorial, I pieced together bits of information from the internet as opposed to reading the appalling 130 paged manual (read here) which is written out in long form instead of using a freaking screenshot to tell you what everything means. Argh. After an unnecessary amount of time wasting and trial and error you’ll eventually get the hang of it.

After finally making your way through the army of kamikaze rats, you’re presented with a top-down world map marked with the nearby town of Shady Sands. You’ll learn that venturing out much further will only lead to overpowered enemies and a series of stop gaps that don’t have much use at this stage in the game due to your limited supplies. The map doesn’t disallow players from diving head first in the deep end, it is entirely open-ended, but the initial state of the player binds them to nearby safety zones. Metroid appears to be open-ended but caps players with power-ups, Fallout does so with the heightened difficulty because of a lack of inventory, weapons and ammo and decent statistics. This form of limitation radiates out from Vault 13 so it’s a very natural form of persuasion.

Just making it this far is a challenge—a 2-part one at that, as you’ll need to first grasp the rules of the game and then figure out a way to survive the harsh landscape of the wasteland. Both of these factors have undoubtedly caused many players great frustration. My brother is an example of someone who gave up early on.

Shady Sands

If the rat cave was a tutorial on combat, then Shady Sands is a tutorial on social mechanics. Well, actually Shady Sands could be an extended tutorial of combat if the player so well chooses because Shady Sands is a really an introduction to player freedom before anything else.

When players enter Shady Sands they are greeted by 2 guards. If the player still has a weapon equipped (which in all likelihood they will as there is no reason to de-equip it) the guards will ask the player to remove it. Right here is moral choice and freedom. The player can choose to ignore the guards, in turn starting a fight or conceal their weapon and have access to the village. The interplay here is just fascinating, I tried both approaches on different saves and here’s what I got:

Aggressive Option (player doesn’t holster weapon)

-the doormen will attack the player

-the player can flee or attack

————attack

—————-if you defeat the guards, you can take their loot from their bodies

—————-other people in the village will pursue you as well, reverting to attack/flee option

———————attack

————————you can effectively kill everyone in the city and raid the whole place dry

————flee

—————–leave the doormen and the screen, state of doormen is back to neutral

Peaceful Option (player holsters weapon)

-the player is treated as a wanderer which means that all the facilities in the town are available to you such as the advice from the doormen, a healing centre, bartering and trade

-the peaceful option opens up a microcosm of other choices each with their own separate avenues

As we can see, a very natural occurrence in the wasteland (defending one own’s turf) leads to numerous ever-changing possibilities for the player to react to (interplay). I took the peaceful option, so let’s continue the game from there.

Interactions in Shady Sands

From the onset Fallout establishes a high precedence for player vulnerability and the interactions and decision-making in Shady Sands are all pertinent to this element of survival. Depending on your decisions, NPCs will cough up tangible goods and money, act as safety net for levelling up and so on. How you get them is up to you. Here are some further examples of player choice and interplay:

Problem: Earning money and goods

Solutions: Trading you wares up with good deals until you earn more, pickpocketing the cash and goods

Example of Interplay: There’s a risk that you will get caught pinching money and the villagers will turn on you. Trading wares requires many interactions with people in order to nab the best deal.

—

Problem: Getting Ian to join you

Solutions: Choose the dialog option that pleases him or pay him a fee of 100 bottle caps

Example of Interplay: Having Ian on your side radically changes the combat portions of the game as he’s another character with their finger on the trigger. He makes the exploration of Vault 15, the radscorpion caves and latter exhibitions considerably easier.

—

Problem: Radscorpion invasion plaguing the town and making villagers sick

Solutions: Go to the radscorpion cave and defeat the scorpions or don’t

Example of Interplay: If the player defeats the scorpions then their tails can be gathered and given to the town doctor who will use the tails to make an antidote for the poison and give you a sample. Later you can use the antidote to heal people and gain experience. The town elder will respect you, the gate keepers will offer additional advice. Later they will call on the player to save Tandi from an opposing faction, leading into another story arc.

Comments on The Rest of Shady Sands, Vault 15, Radscorpion Cave and The Raiders’ Camp

The rest of Shady Sands

As I mentioned previously, I can’t bear reading “too much” text in video games. Playing Fallout, I was still stubborn about this point and it was to my own detriment. This first tutorial chunk has taught me that to survive the wasteland you need 3 things: goods, decent statistics and proper intel. You’re simply far too underpowered to be lacking in any of these. By knowing the lay of the land, you can avoid venturing off aimlessly and wasting precious time and resources. The advice the NPCs doll out then is just the kind of support you need. The dialogue also has a dual function of adding to the lore of the game as well as simultaneously dropping hints. NPCs are thoughtfully spread out too so that prioritised characters with something to say are marked by their unique appearance and convenient placement, while peasants are placed apart and interaction with them doesn’t launch into the dialogue/trade menu.

In Shady Sands, the gatekeepers are placed right at the front and communicate the most necessary information, hold the most useful items for trading/stealing as well as tell you who can give you more info.

Vault 15 and Radscorpion Cave

The radscorpion cave is a little obscure as you can’t reach the location on foot, but are instead teleported there by one of the gatekeepers who reckons he knows the way. The location of Vault 15, on the other hand, is marked on the map after you prompt your partner Ian for directions. Both areas are extensions of the rat cave tutorial at the start of the game with the ante raised some. I found that these areas helped me fall into the rhythm of combat since fighting and looting is all there really is to do in these parts. On reaching the bottom floor of the abandoned Vault 15, I was surprised that there wasn’t some kind of reward. I suppose this is part of the Fallout charm.

The (Kahn) Raiders’ Camp

After obtaining the antidote from the town doctor, you learn from the gatekeepers that one of the girls in the village Tandi has been kidnapped by the Raiders (who you learn earlier have been ransacking the village). The village leader obligates you to save her and you can do if you wish.

The Raiders are one of the wasteland’s many factions. Their base is in an decapitated house just south of Shady Sands. Guards are settled out in smaller tents around the make-shift base. Like Shady Sands, you need to holster your weapon before you’re allowed access. Once holstered, you can walk straight in and negotiate with the leader Garl on Tandi’s release. There are several ways to tackle the situation:

- Barter 650 bottle caps worth of goods for her

- Fight the leader in a one-on-one cage match

- You can smooth talk your way to her (given you have the necessary stats)

- Shoot through the guards and kill Garl

- Follow Garl’s request and shoot one of the slave girls

There is clearly a great deal of flexibility in how the player can tackle the situation and each option supports key strengths that the player could have rolled into their character. In order of my listing above the options support bartering, combat, conversation skills, weapon skills or just utter failure (let’s just assume that killing innocent an abused ladies is the failure option).

Conclusion

At this stage I hope that you get a basic idea of the degree of freedom and the resulting interplay present in Fallout. It really is quite fascinating to explore the different outcomes of the player’s choices. Some of the stories I’ve heard of inspire me to be more experimental with my approach. It will take some time before I get to the next entry, so there’s still time to join in if you want. Otherwise, please enjoy the reading below.

The Guilt Trip Over Drip-feeding Through Point and Click Adventure Games

October 15th, 2010

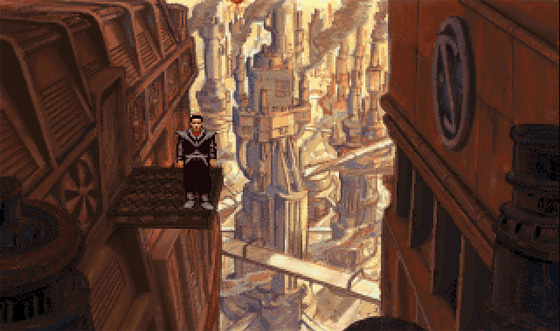

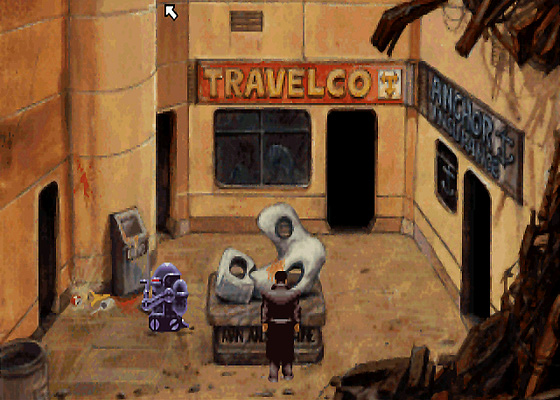

Recently I completed Beneath a Steel Sky (which you can conveniently download from Good Old Games for free) and fessing up it’s probably my all time favourite point and click adventure game. The interface is minimal and elegant, the puzzles largely built on clever logic (that is, you can solve them yourself), the dialogue—while completely misreading Australian culture at times—is sharp and generally laugh-out-loud funny and, finally, the artwork is done by no less than Dave Gibbons of Watchmen fame. So, essentially, Beneath a Steel Sky ticks all the right boxes for an old school adventure fan. However, I may as well say the whole truth while I’m at it: none of this stopped me from occasionally drip-feeding my way through on a FAQ.

It’s a cardinal sin, an invariable trademark of a cheat, I know. The puzzles are the glue keeping the whole experience together, the gameplay in its entirety (apart from dialogue options and random asides) and to dodge the puzzles like this is to basically negate the game altogether. So why is it that when playing point and click adventures, even the good ones like Beneath a Steel Sky, I can’t resist the temptation of peeking at a walkthrough?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lyZrgvoQFNMWell, the genre isn’t all that fun most of the time and by most of the time I mean when the potential solutions to a puzzle aren’t readily apparent to the player. I spend the majority of my time in these games flailing around without a clue on what to do next instead of actively solving puzzles. Granted, Beneath a Steel Sky isn’t as bad as some, it still threw up roadblocks from time to time.

My frustration stems mainly from the imbalance of challenge and guidance. Ideally, as soon as a player obtains a new item, alarm bells should be going off in their head as to where and how they can use the item in conjunction with the environments and props they’ve previously encountered (or, alternatively, just keep it in storage until a future opportunity arises). The game needs to manifest clues throughout the environment, NPCs and props. Furthermore items ought to function as one expects, ie, a knife can be used to cut things and not as something to row a boat with. Through these means, the most reasonable interactions are accepted and the game can lead the player to the goal without giving them the answer.

Metroid and Zelda do this really well. In these games, players will often stumble upon devices/areas that can’t yet be operated or reached until the player gains a certain ability, as such the player makes a mental note of it (or in the case of Phantom Hourglass, they scribble it down on their map). Later in the game when the player finally gains a new ability, they already have a few ideas on where the item/ability might be needed, if not know exactly what to do with it. Furthermore, the abilities/items follow the principle of form fits function and often NPCs, like Navi or villagers, will drop hints. Puzzles in a point and click adventure game follow the same structure where players will first come across a series of situations and then acquire the inventory to solve each dilemma. For example, at the start of The Secret of Monkey Island the player will first make their way through the town, listening to the problems of the towns people before they find the necessary tools to tackle the problems one-by-one. It’s in these first instances of each section of gameplay where the seeds must be planted in the player’s brain.

Another point to consider is that in a point and click adventure items are often used once and then discarded or used up in the one go which means that, unlike the 2 previously mentioned games, the interactions that accompany each item in the inventory often only occur once. Since each item can only be used once, point and click adventures cannot be quite as obvious as a Zelda or a Metroid, otherwise players will solve the problems too quickly. It’s all about striking a balance between challenging and do-able, much of this occurring in the investigation stages of the game.

Now that we have a general idea of when and how these games equip the player for problem solving, we can analyse the puzzles and lead up to the puzzles in Beneath a Steel Sky which made me resort to a FAQ, judging whether the game was reasonable or not. I will use the criteria that I mentioned above (primarily: whether the items fit its reasonably assumed function and how clues and tutorial are internalised within the environment, props and NPCs) as well as evaluating the construction of puzzles. You’ll have to excuse some of the weak explanations as I didn’t note take while I played the game.

The Factory and Upper Levels

Early on, Beneath a Steel Sky follows pretty standard logic and poses little trouble to the player. The inventory is standard factory equipment like an iron bar, WD-40, a spanner and the ID card which interfaces with the LINC terminals. These terminals offer some humourous details on the characters as well as slipping a few hints through. Joey (the smart alec robot) and the NPCs are also very helpful. Otherwise the inventory is rather practical and straight forward (the steel bar has multiple uses as a rod, the spanner is used to undo bolts, the puty to hold things in place etc.). However, the game had set no clear context on how to overload the machine, this part seems rather trial and error due to the needlessly complicated steps involved, even if the items have sensible applications.

I found that as Foster and Joey made progress, the puzzles became a little less practical. For instance, in the upper levels after you drop Lamb’s social status down to a D-LINC (no social rights) in Pott’s factory, you then have to wait for Lamb to ride the elevator to the upper levels and then get stuck as he fails to activate the elevator terminal to get back down. This doesn’t make a lot of sense as you lower his status before he takes the elevator up, so how is he even allowed to take the elevator to the upper levels? Then once you bump into him, you need to exert all dialogue options before the next part is prompted. The construction of this puzzle is longwinded, defies the game’s own logic and is based partly on chance (in that you need to run into him first and can easily miss or overlook the prompt).

Linc Space

Linc Space, the computer program that you can hack into, forced me to use a guide almost for the entirety of these reoccurring sequences. Outside of Anita (who only tells you what needs to be done in Linc Space), this part of Beneath a Steel Sky is really unaccounted for. Foster is transported into the simulation with some arbitrary tools and objects that are given no pre-set explanation. The player knows their objective, but without any context or support behind these random tools, these sequences are mostly trial and error. For instance, I used the unzip tool to open the secret files, but once opened, the examination mechanic (right click) wouldn’t allow me to read the files. This is needlessly impractical.

Belle Vue

On the ground level, the gag with Mrs. Piermont’s dog reminds me of similar joke puzzles from Monkey Island and Grim Fandango. While it’s not as farfetched as using cooking oil to peel the tattooed map off the back of a sun baking pirate, it still falls under the category of humourous at the expense of sound logic. Admittedly, the dog biscuits should be used with the dog, but the rest of the puzzle is contrived.

Linc Base

While there were a few more bumps on along the road, the end chunk of the game, just like the first is fairly straight forward as the Linc base is quite contained and the connection between the environment and the inventory is much clearer. Can’t reach the seal to a shaft? Use the iron bar to prod it open. Can’t enter the lab with the android? Insert Joey’s circuits into a spare robot shell. All very natural interactions given the tools you have available.

In returning to the question (So why is it that when playing point and click adventures, even the good ones like Beneath a Steel Sky, I can’t resist the temptation of peeking at a walkthrough?), the reason is that, as evidence by the examples above, some of the puzzles in Beneath a Steel Sky don’t assist the player in realising the solution, they just send the player in blind. The environments and characters often don’t strongly embed tutorial, so when there’s a tricky puzzle or the tools do not function as the player might assube it all falls apart.

To extend beyond this analysis and into other reasoning, it becomes difficult to refuse using a walkthrough when it comes packaged with the game itself. The fact that a play guide was included, makes the reliance on it easier to bear, as opposed to searching yourself. The presence of the guide suggests that Revolution Studios knew that players would likely get stuck and went to the appropriate means of resolving the problem. And when the player follows this supposition, it’s hard to feel guilty. It’s obviously a band-aid solution that fails to rectify the bad design.

As I continue to play around with this genre, I want to take these design principles a little further in my analysis. For now though, we’ve established a rather handsome base to kick off future research. Please feel free to try Beneath a Steel Sky yourself to see if you agree with my arguments here. The PC version can be found free here, while an iPod version can be bought here.

Additional Reading

Beneath a Steel Sky Walkthrough

Beneath a Steel Sky – Hardcore Gaming 101

And Yet It Moves Comments

October 10th, 2010

The clip above quite succinctly demonstrates the core premise of And Yet it Moves, but to put it into words: you’re a crudely-drawn paper man who travels a bizarre mish-mash world of 2D textures that resemble a natural environment, the entire world can be rotated at will left or right, sending the paper man tumbling in the appropriate direction.

The trick to AYIM is the rotation mechanic which steers paper man (and the objects and structures which support him) into areas otherwise out of reach. Such a mechanic could make a platformer like this disorderly, but the levels are smart and well thought out, ensuring that players aren’t ever asked to do anything too extreme. Judging by the credits too, AYIM was heavily playtested during development. What really saves AYIM though is the fragility of paper man and the way momentum isn’t broken by the rotations of the screen. These limitations on the player transform the levels into a series of spatial puzzles. It’s tricky to judge the exact amount of inertia necessary to topple paperman, so you’ll constantly be trying to push the boundaries of what you can do with him. This part of the players behaviour fosters an addictive quality played on by the frequent and rather convenient checkpoints that spur you on for another go.

And Yet It Moves tells narrative through two means, the first is the transition of environments every few levels or so, starting within a cave, leading into the jungle and then into a surreal wonderland. The order of levels also makes sense from a difficulty standpoint as well, with the interiors of a cave providing less bottomless holes and openings than the jungle (with its sky and so on). The surreal wonderland is then an excuse to take the design in a much more crazy and realised direction. The second means is through the gimmicks punctuating the later halves of the levels. These gimmicks include sending a banana through to an angry ape without squashing it, moving yourself and a duplicate through a flipped, symmetrical maze and moving an army of bats through a cramped cavern. Each of these instances take advantage of the rotation mechanics to great effect while adding a nice bit of context to the levels.

The simplistic charm of these interesting elements is also present in the kooky music arrangements, stock image textures and the “bocha-chicka-wock” sound effect punctuating paper man’s walk. And Yet It Moves may be considered short for the few hours it will take you to complete, but it’s not really considering that not a minute is wasted on superfluous fluff. The rotation mechanic teamed with the physics and frailty of paper man and the well-crafted levels create a harmoniously-designed, smart puzzle-platformer that with a suitably trim play length.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99