Puzzle Quest – Variation, Lastability and Repair

November 8th, 2010

It’s rare that I shelve a game before I complete it. Usually, I try to pay the cheapest price and get the most mileage out of a game. This is a given considering the inexplicable 40-50% price mark-up on Australian games over the States. Further consider that our dollar has recently floated with the USD. However, Puzzle Quest (which ironically enough I didn’t buy, my brother did), has forced me to send it into early retirement on my shelf (also ironic since it’s a digital download, so there’s no shelf) due to the statistics and abstraction that I was previously suspicious about and the implications it has on the game’s variation. So here’s the breakdown:

RPG Meets Competitive Bejewelled

Puzzle Quest is basically a competitive modification of Pop Cap’s mega success Bejewelled (play here) placed in the shell of an RPG. “Competitive Bejewelled” constitutes the battle system with everything else held together through an overworld map with linear routes that connect to towns, caves and everything else you’ve come to expect from RPG maps.

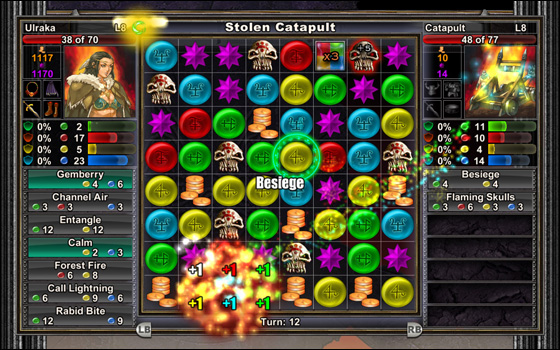

Bejewelled is modified so that the playing “board” contains skulls that when lined up reduce your enemies HP. The coloured gems on the board represent mana that accumulate on every match-3 or above. The mana goes into spells which, once the necessary points of mana are gaineh, can be activated on demand and take the player’s turn. Spells usually impact the layout of gems or temporarily boost the player’s stats and attributes. Examples include poisoning you’re opponent, changing the colour of a gem type, increasing defence or switching HP for a type of mana until the manna depletes fully.

Underpinning the core mechanics of “competitive Bejewelled” are a few sets of staple RPG abstraction systems tied to the player’s avatar. These variables have an invisible presence within the match-3 gameplay. We’ll start with the raw stats which I have pasted outright from the following FAQ:

“Earth Mastery: Increases the amount of Mana you gain for matching Green Gems, increases the chance of taking an extra turn for matching Green Mana, and increases the chance of creating a Wild Card for matching Green Mana.

Fire Mastery: Increases the amount of Mana you gain for matching Red Gems, increases the chance of taking an extra turn for matching Red Mana, and increases the chance of creating a Wild Card for matching Red Mana.

Air Mastery: Increases the amount of Mana you gain for matching Yellow Gems, increases the chance of taking an extra turn for matching Yellow Mana, and increases the chance of creating a Wild Card for matching Yellow Mana.

Water Mastery: Increases the amount of Mana you gain for matching Blue Gems, increases the chance of taking an extra turn for matching Blue Mana, and increases the chance of creating a Wild Card for matching Blue Mana.

Battle: Increases the amount of damage you deal when matching Skulls, increases the chance of taking an extra turn for matching Skulls, and increases the chance of creating a Wild Card for matching Skulls.

Cunning: Increases the effect that Wild Cards have on other gems, increases the amount of money you gain for matching Gold Coins, increases the chance of taking an extra turn for matching Gold Coins, and increases the chance of creating a Wild Card for matching Gold Coins. Also, at the start of battle, the person with the highest Cunning goes first.

Morale: Increases your Life Points, increases the chance of taking an extra turn for matching Purple Stars, increases the chance of creating a Wild Card for matching Purple Stars, and increases your spell resistances.”

As the player defeats enemies and matches up experience gems on the grid, they’ll gain more experience points which go into player levelling that increases these stats. These statistics can be further increased through a 4-slot equipment system for helm and crowns, clothing and armour, weapons and misc items. Your wardrobe can modify the aforementioned stats, another set of stats for your elemental resistance (a percent, not an integer) or add various perks to the player such as decreasing enemy attacks over 5 HP by 1 HP or decreasing the damage sustain by a rival the more they use their spells.

Rounding out the system is the occasional buddy mechanic whereby characters in the narrative can join you in battle when you encounter an enemy type that fits their speciality. In reality they don’t really join the player, they just give a little heads up and then increase some stats for the duration of the battle.

The battle screenshot below summaries what has been said above quite nicely:

The battles are connected through an overworld hub which offers direct paths from place to place. You make progress by completing quests for neighbouring kingdoms and factions which open up other kingdoms which can then be overthrown. Once overthrown the castles accumulate money, adding to the wad of cash built up from battles and matching coin gems. Effectively Puzzle Quest is a game of imperialism.

Kingdoms have a variety of uses beyond handing out quests. The pub offers rumours some of which require a monetary donation (still unsure of why rumours are important), shops obviously sell equipment and lastly there’s the citadel. After earning a little dough you can build the relevant structures to get some use out of the citadel. Once full-funded, the citadel allows the player to research spells by using enemies captured on the field (more on that later), you can improve your core stats by monetary donation, train mounts (haven’t reached this part yet), and forge new items with runes which you can acquire by searching some areas and defeating the monsters within.

Variation and Lastability

With the necessary overview out the way, we can look at this issue which has sucked all my enjoyment out of Puzzle Quest. The main problem is that progress in Puzzle Quest is tied to the underlying system of abstraction (player statistics, equipment, companions) and not the core rules of the game (“competitive Bejewelled”). Therefore, while the numbers change, the core gameplay remains largely the same throughout the entire experience. This is all compounded by the fact that every quest is invariably a battle; the same battle played over and over again with only mild statistical variation.

Many RPGs employ the same model of statistical variation which effectively amounts to the same consistent pattern of attack-attack-heal gameplay that these games begin with, albeit with larger numbers and more extravagant spells. Nothing truly changes from beginning to end as the player’s stats rise along with that of the creatures around them. Players can only defeat stronger enemies if they’ve spent enough time ploughing through inferior ones. It’s unsurprising then that since Puzzle Quest uses the same style of variation, it faces the same problems as many RPGs. The battles become repetitive grinds, very little changes and the same flow of tactics are suffice. Puzzle Quest only really lasts as long as the player’s interest in Bejewelled. Once that’s over then there is little reason to continue playing.

Personally speaking, it was the siege missions (where you overthrow a kingdom by defeating the castle) that prompted me to write this article. I would take on these difficult battles where the statistics and odds where weighed against me, so that I could artificially create challenge for myself, forcing myself to find the best matches and hinder any chance of the opposition taking a blow. Sadly, even superior tactics couldn’t overcome the fact that I was a peon by statistical comparison.

Repair

As we’ve established, Puzzle Quest is a game of two halves: the competitive take on Bejewelled (puzzle) and the RPG overworld, statistics and sub-systems (quest). It even finds its way into the dichotomised title. However, the RPG statistics and the system of variation it imposes are highly detrimental, it would be much better for Puzzle Quest to use the same method of variation as its other half: puzzle games.

In puzzle games with a rigid core system of primary mechanics, the mechanics themselves don’t change in order to create variation, but the conditions of play do. Tetris is a good example. In Tetris DS, Nintendo SPD Group No.2 don’t alter the foundations of the game (that would be ill-advised considering the already great design of Tetris), but instead introduce new modes. These modes include standard, mission, touch, push, catch and puzzle. Here is an outline of these modes taken from Wikipedia:

Standard Mode

Standard mode plays much like traditional Tetris….Standard mode can be played as a one player marathon, multiplayer with two players or one player versus a computer controlled opponent.

Mission mode

Mission mode can be played competitively, or as a marathon to beat your own score. The top screen displays your objective or “mission,” while the bottom screen displays the playing field. A timer in the form of red hearts slowly disappears; when a player completes the objective, the hearts fill anew and the player is assigned a new objective

Push mode

Push mode is a competitive play mode for two players, or one person versus a CPU controlled opponent. Both players start with a 1×1 block floating in their field, and must place Tetriminoes on that to form a base (If a Tetrimino is dropped where it won’t land on anything, it will simply fall out of the screen). Whenever two or more lines are cleared simultaneously, the player’s side of the pile moves down, “pushing” the opponent’s side upwards (The player’s side is seen on the top screen, while the bottom screen shows the opponent’s side upside-down, since the bottoms of both players’ piles push against each other). The goal is to push the pile down so it overlaps the opponent’s danger line.

Touch mode

In Touch mode, a player uses the Nintendo DS stylus to “touch” and “slide” static Tetriminoes to create rows. When enough Tetriminoes have cleared, a cage of balloons is released.

Catch mode

In Catch mode, a player controls one central block, which can be moved in all directions and rotated. The player “catches” falling Tetriminoes, which adhere to the central block; once a player has a segment of 4×4 or greater, it will flash for ten seconds, then detonate. The player can then use the explosion to destroy Metroids, the enemies, or Tetriminoes. While the 4×4 square flashes, more blocks can be attached to it to gain more points when it detonates (the flashing portion only expands if another four blocks are added to one of its sides). Pressing X will immediately detonate the blocks. If any Tetriminoes fall beyond the boundaries, the central block is hit by enemies, or a falling Tetrimino touches the central block while it is being rotated, the player will lose energy. Energy is depicted at the bottom of the screen as a bar, and some energy is restored when a 4×4 or greater area of blocks is detonated. If energy runs out, or Tetriminoes are stacked so far that the central block is longer than the entire screen, the game is over. Catch mode features a Metroid backdrop.

Puzzle mode

In Puzzle mode, the top screen displays the playing field that is already several lines high, with several gaps; the bottom screen displays a limited selection of Tetriminoes to choose from. A player must select the shape and orientation of a Tetrimino to fill the gaps and clear the screen. There is no time limit.

As we can see, Tetris remains the same, but conditions are added or changed to rework and diversify the core puzzle system.

In fairness, Puzzle Quest does include a degree of this type of variation in the form of capture battles. Capture battles are self contained puzzles with only a handful of gems stacked upon each other. The player must re-align the gems so that all gem match up and are removed from the board. These battles pop up as an optional alternative to regular battles where the enemy can be captured and researched for spells at the citadel. Similarly, crafting spells tasks the player with battles that require the player to match several scrolls and a fixed number of mana gems.

Spells, are also something of an outlier, and interject additional elements of strategy into common battles. The spells which change the core elements (gem types, HP, mana, layout of gems) are the ones that are truly effective. Furthermore, spells require specific amounts of mana to be cast and that fuels the player to strategise which colours to align. The strategy here is dual layered as the player wants to align the mana they need to cast spells and at the same time obscure their opponent from gaining the mana they need to cast their most powerful spells. Most spells themselves also change conditions on the board that have ramifications for both players and again, there is a element of strategy further involved in deciding when and where to activate spells. As the player gains more levels, they also learn new spells which diversifies play somewhat.

When it comes to the crunch though, the quests in Puzzle Quest fall under the one mode of play (which I will call “battle mode”) and nothing else. What Puzzle Quest needs is an array of new match types or scenarios which alter the way the player interacts with the “competitive Bejewelled” component. These variations should then be sprinkled in amongst the “battle mode” quests as to deviate from the regular battle to the death gameplay.

Stay tuned for the next instalment where I offer some suggestions for new modes of play for Puzzle Quest.

Conclusion

Puzzle Quest is a straight combination of the puzzle and RPG genre where the primary puzzle mechanics (a competitive modification of Bejewelled) take the form of battles and the RPG elements constitute underlying abstraction and an interface for progression (a map and the increase of statistics as the player levels). Puzzle Quest advances on the player’s stats (RPG side of the fence) which have little influence on the core gameplay (puzzling) and therefore there is little variation in the core gameplay as the player makes their way through Puzzle Quest. The quests are all exactly the same: battles. For these reasons I tired of the game very quickly, even though the battles (Bejewelled) are interesting.

Puzzle Quest needs more variation to the “competitive Bejewelled” puzzle elements and it ought to look to other puzzle games to for clear examples. Puzzle Quest‘s core elements ought to remain fixed, however, the conditions that govern the game ought to change. That is, by modifying the win state, gems, HP and other elements, and the injecting these new modes of play in amongst regular battles, Puzzle Quest will be a more diverse title and likely to hold the player’s interest for longer.

Aria of Sorrow Review – Centralised Layout and The Tactical Soul System

November 5th, 2010

Aria of Sorrow is a fine improvement over Harmony of Dissonance. I razzed on Harmony of Dissonance for its incompetence at stringing the player from one major interval of gameplay to another. In regards to Aria of Sorrow, you never once stop to think about the layout and you don’t really use the map screen all that much either. You’re too busy whisking off to the next place on the map. Each subsection exit is the closest offshoot route to the entrance of the next which means that there’s minimal backtracking. Furthermore I didn’t feel the need to use a teleport once, whereas I used them more frequently in Harmony of Dissonance.

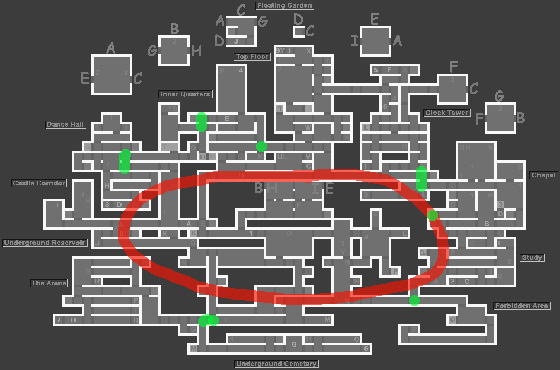

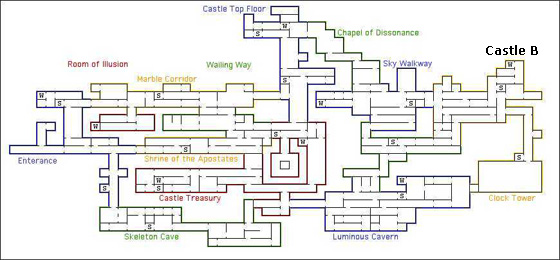

How is Aria of Sorrow such a dramatic improvement? Well let’s take a look at the castle layout.

You can see how each subsection (marked with their squished text titles) connects to a central part (red circle) which the player arrives back, rounding off the chunks of gameplay nicely. You’ll also notice that the subsections themselves are threaded together at various junctions (green dots), allowing for a smooth transition between nearby subsections without negating the overworld hub. This layout means that the player can be strung off to tackle more than one subsection at a time and then return, with minimal fuss, to the central hub and move to the next fresh chunk of gameplay.

What you can’t see on the map, however, is the complete overhaul to the ability system. In Aria of Sorrow there are more significant upgrades this time, including the ability to walk on water, walk underwater, become a bat alongside the regular double jump, high jump and slide mechanics. The former three are all a part of the new Tactical Soul System. These abilities act as devices to draw the player to the entrances of each subsection by interaction points as I described in my Harmony of Dissonance piece. Let’s be a little clearer by using an example though:

When the player begins the game, they explore the central hub area and come across areas that they cannot quite reach or parts of the game they can’t interact with. For the sake of this example, the water level near the entrance to the cemetery makes it impossible to overcome the high wall blocking the player’s path. The player takes a note of this and moves on. Later they will acquire the Undine ability which allows them to walk on water. Receiving this item and playing around with it will likely create a click in the player’s brain, telling them where to go next.

The more abilities, the more opportunities the game has to exploit this technique of letting the player realise their own path. Let’s talk about this Tactical Soul System, shall we? I described it on Twitter like this:

“Soulset [Tactical Soul System] is like the fusion system from Metroid Fusion, however, you can gain abilities from regular enemies instead of just bosses”

So, basically, when the player downs an enemy, there is a chance that they will absorb their soul thereby inheriting the enemy’s ability. There are 3 groups of souls (Bullet, Guardian, and Enchant) and only one soul from each group can be equipped at a time. Bullet souls are sub-weapons, guardian souls are similar to spells and use up magic for the duration of their use and enchant souls boost stats, while some offer temporary abilities (walking on water, for instance). The Tactical Soul System gives the player incentive to actively engage in combat and rewards them with new techniques which feed back into diversifying the combat. I’ve discussed this self-sustaining approach of rewarding players with more tools before in regards to Space Invaders Infinite Gene. In Aria of Sorrow it goes a long way into alleviating the grind that can occur through the mostly spammy combat. It’s a much more fleshed out than the sub-weapon drops plus elemental spell combinations of Harmony of Dissonance. The wide spread of equipable weapons, ranging from your traditional whips to axes, spears and even a pair of guns, is the other element of Aria of Sorrow which livens up the combat.

Conclusion

Aria of Sorrow addresses the castle layout issues of its predecessor Harmony of Dissonance by using a central hub to connect subsections together and avoid messy overlap in design. The core ability set has increased and works more effectively as a device to lead players from one area to another based on interaction points left at subsection entrances on the main hub. The Tactical Soul System, like in Space Invaders Infinity Gene, diversifies play on the players own participation and works effectively at reducing the grind that may come from combat. Overall, Aria of Sorrow is the better of the two games with cleaner castle design and a the Tactical Soul System which encourages the players to participate more with the combat, rewarding them with more tools that inturn make play more varied.

Necessary Aside for stuff that needs to get off my chest:What really irks me about Aria of Sorrow though is that 3 specific souls are required to see the real ending. Argh!

Additional Readings

Castlevania: Aria of Sorrow – Castlevania Dungeon

Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance – Castle Layout and Ability “Stringing”

November 2nd, 2010

My experience with Harmony of Dissonance can be summarised like this: it took me about a month of on-and-off play to complete Harmony of Dissonance, whereas I beat Aria of Sorrow in 3 days of solid play. My playtime was drawn-out in Harmony of Dissonance because of numerous road blocks which brought my playtime to a standstill.

Harmony of Dissonance‘s castle, as you can see from the map, is a muddle of interconnected subsections (marked by their text labels) without a central hub to string players neatly from the end of one area to the start of another. Subsections effectively act as routes to other subsections bottlenecking progress and creating large amounts of needless backtracking. That is, if you need to get from the Sky Walkway to the Entrance, you must backtrack through 3-5 subsections depending on which route you take. It’s also very difficult for the player to mentally compress this amalgamation of play zones into a coherent order.

The player travels from the entrance to the (uppish) left of the screen to the point labelled “castle b” (they teleport between the 2 masses of areas), then back underneath to the entrance and finally to the central box. At any point in the game there is more than one path to take. This number doubles at the “Castle B” point on the map where the entire castle is duplicated and the player can switch to the slightly modified palette-swap version through special portals. Because of the large number of avenues and potential dead-ends for players, Harmony of Dissonance ought to utilise a combination of techniques to gesture players towards the right path.

The best measure for guiding the player in a Metroidvania game is to create a baiting system around the player’s not-yet-acquired abilities. You do this by starting the player off with only basic functionality, dropping interaction markers for not-yet-acquired abilities throughout the environment and then finally coughing up the abilities necessary to interact with said interaction points. The interaction markers (a grapple point, a platform that’s just too high to reach) plant seeds in the player’s mind which they mentally flag down, then once they obtain a new ability (grapple beam, double jump) and draw the connection between the new ability and the interaction point, a “click” goes off in their brain. They’ve done it! The player thinks that they are so smart for figuring it all out and rushes to where the interaction marker is (conveniently, the next part of the game) with haste. This is a tried and true design element of Metroidvania games.

Harmony of Dissonance only has 3 obtainable abilities to limit the player’s progression: Lizzard’s tale (slide), Sylph Feather (double jump) and Griffith’s Wing (high jump). Considering the game’s size, 3 abilities is far too few to string the player from one part of the game to another. Furthermore, there’s a very lax reliance on these already too few abilities. They’re only ever properly needed a few times throughout the whole game. Once at the junction point to the next area and then maybe a few times after that. Because there are so few interaction points in Harmony of Dissonance (and the nature of the upgrades mean that they can’t be made explicitly clear, ie higher platforms as opposed to a clearly defined grapple point), this stringing dynamic is hardly at all in play. An exception to this is the suggestion of a raised room on the exterior pathway to the castle, a seed that plants itself deep in the initial instances of the game.

Because the number of abilities is so few, Harmony of Dissonance uses some peripheral, inventory items to replace abilities as limiting factors. As these items are really just nothing more than added text in your menu, it’s not always easy to draw the connections between an piece of inventory and something in the environment which requires it. A key to a door is simple enough, but when a key is Maxim’s braclet and it opens a magic door, it gets tricky. And anyways, it’s easy to forget that you even have a key when you can only use it in the one instance. Other issues arise when you use a key to open a floodgate that you can’t find on the map, effectively asking the player to put the key in a random hole while the supposed flood gate opens.

Conclusion

Harmony of Dissonance demanded entirely too much of my time and patience due to a confusing left-to-right castle design and a lack of effective stringing through ability baiting. The castle connects subsections together like Lego and not to a hub-like core which reduces backtracking and unclear, overlapping design. The stringing proved weak because only a handful of abilities were used and they were stretched over the whole game. Furthermore, inventory items were occasionally used as weak replacements.

Additional Readings

Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance (2002) – Castlevania Dungeon

Castlevania Harmony Of Dissonance : Playing As Simon Belmont, Megaman And Mario

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99