An Overview of Trans-media Storytelling and Video Games

November 21st, 2010

Sonic The Hedgehog: Triple Trouble is a once-off collectors edition comic, part of Archie Comic’s long-running line of Sonic comics which my news agency imported from the states during the mid-nineties. It was also, thanks to some convincing from a friend, my very first comic. After Triple Trouble, I bought another 6 issues before my quiet country town newsagent stopped stocking the line altogether, effectively killing off my interest in comics with one fellow swoop.

Skip forward to the end of last year and my brother is placing an order through Amazon on my behalf for 3 of Alan Moore’s esteemed graphic novels; my interest has re-emerged. Having thoroughly enjoyed the selection of imported comics, I walk into Adelaide comic book store Pulp Fiction Comics in search for the next series to invest in. Yet despite still being a self-confessed comics newbie, the trans-media pollination ensures that the environment isn’t an unfamiliar one. World of Warcraft, The Legend of Zelda, Dead Space and Prototype are just a sampling of the familiar brands I see on the store shelves. As I walk through the store, trying to gain ideas, my mind drifts back to Sonic and I’m reminded of the trans-media connection which has always existed between games and comics.

Trans-media Storytelling: A Definition

Trans-media storytelling is a concept first put forward by academic Henry Jenkins in his book Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide to define storytelling told over multiple forms of media. The crux of the idea is that each form of media supports the others and provides the reader with different, medium-specific viewpoints in which to interpret the text as a whole. Naturally, these types of texts are rich in content and artistic styles, commanding a dedicated user base who are required to spend more money to invest in the entire narrative web. In this regard, building a trans-media franchise is like building a universe.

With consumers accessing their news and entertainment through a range of different avenues (physical purchasing, iTunes, Netflix, Gamefly, RSS feed) on a range of different platforms (mobile phone, TV, MP3 player, game console, PC) it’s become more difficult for news and entertainment companies to commodify their target audience. Their markets are fragmenting due to the enormous amount of choice that new technology has given consumers. Establishing, or extending out to become, a trans-media franchise is therefore a successful way to connect audiences spread over various avenues and mediums, therefore reclaiming corporate control over the market. As can be seen by the likes of The Matrix, Twilight or Pokemon, the financial payback and consumer loyalty in these investments are worthwhile. In this regard, building a trans-media franchise is like building the next phenomena.

Two Points of Contention

And here we hit an enormous point of contention: how do we distinguish a trans-media franchise from a series of adaptions? Well, adaptions, say that of a comic to a video game or a book to a film, do not necessitate reading and interpreting texts over multiple media—and thereby through the lens of each respective medium—as there is no fragmentation. It’s all the same story, just in different forms. Franchises which use this approach to storytelling are what we’d call a media franchise and they constitutes the majority of cross-medium production. Scott Pilgrim which has had its narrative adapted from a comic book to a movie and video game is an example of a media franchise.

The Matrix, however, is a trans-media franchise as Enter The Matrix, The Animatrix and the anthology of comics all support the viewing of the films by providing context on characters and backstory. Consumers who only watch the movie are given a rather abrupt introduction to characters like Niobe and Ghost in The Matrix: Reloaded who first make their appearance as protagonists in the game Enter the Matrix. In fact, this aspect was a point of criticism for movie critics, yet fans who’d played the game didn’t find the introduction to be jarring at all. The Animatrix, particularly The Second Renaissance Part 1 and Part 2 shorts explain how the world as we currently understand it was overtaken by machines. These parts of The Animatrix, as an example, give credibility to the origins of the series as layed down in The Matrix and support the ideologies in the characters in Zion prevalent in Matrix: Revolutions. Just by these few examples, we can form an understanding of the narrative complexity at work. In this sense, trans-media franchising is the process of creating a universe or a phenomena, whereas media franchising is about transferring one narrative to other mediums.

A Case Study (Past-Present): Resident Evil

There are a number of key video game franchises which have evolved into trans-media franchises (Final Fantasy, Super Mario Bros.), but, hindering the definition, also include straight out adaptions as part of their cannon, making it difficult to classify these franchises into one school or the other.

Let’s use Resident Evil as a model to better understand this dilemma. There are Resident Evil games, books and films, with the games forming the central narrative. All of the books bar two (Resident Evil: Caliban Cove and Resident Evil: Underworld) are based on the video games. Resident Evil: Caliban Cove and Resident Evil: Underworld support the events from the video games since they are side stories which flesh out the role of Rebecca Chambers and the Umbrella corporation respectively. However, several of the books (both adaptions and side stories) contradict details made within the video games (the location of Racoon City is often confused, for instance).

The relation to the films are equally complicated. Capcom claims that the live-action movies aren’t canonical, however story elements from the movies have found their way into the video games (thanks Cavia!). For example, Red Queen from Resident Evil (movie) was adapted into Resident Evil: Umbrella Chronicles. Furthermore, the recent CG film Resident Evil: Degeneration officially ties together the narrative threads between Resident Evil 4 and 5.

Even within the video game medium, the fundamental plot is still a bit of a blur. Side stories (Umbrella/Darkside Chronicles, Outbreak etc.) reference the plot of the main games, but rarely do the main games reciprocate the citations. This loosens the strings between each production, effectively illegitimising the credibility of the side narratives.

Since Resident Evil was never originally intended to be a franchise spanning multiple media, and such expansion has seemingly been driven by the profit motive, Resident Evil’s narrative has become severely mangled over the years. Alas, despite the messy story, I think it’s fair to claim that Capcom have created a universe with this property, which makes it one of gaming’s early and more significant trans-media franchises.

Awkward Growth

Resident Evil is unfortunately a pretty typical example of expanded narrative, or rather, the milking of a franchising for extra capital. For trans-media narratives to work properly keen commitment is required on behalf of publishers. It is a much better idea to begin with the intent of creating trans-media property and then acting on this principle. On the other hand though, creating an expansive narrative over several mediums is a risky proposition. Usually it’s only at the point when mass success is realised that introducing other media becomes a priority—even though the threads for added narrative haven’t been layed. The next game is an example of a production where the decision to become trans-media was made too late in the creative process but before the release of the initial product. That is, a step between a Resident Evil and a trans-media franchise built from the ground up.

A Case Study (Present): Dead Space

Although it has dissolved into a confused narrative mess, Dead Space is an example of a more genuine attempt at crafting a trans-media franchise, having decided to become trans-media from the outset. The problem with Dead Space though is that the original game was scripted before the 4 prequels which have subsequently preceded it and therefore the core narrative doesn’t acknowledge the later prequels. As a result, it’s hard to care much for the continuity without the narrative references to keep it in place. Furthermore, each of the prequels tell fairly similar tales of survivors trying to escape from the effects of the Red Marker, only the recently released novel, Martyr deviates from this clichéd perspective.

With Dead Space 2 set it arrive later this year it seems that EA are willing to keep this trans-media thing going with a new graphic novel Dead Space: Retribution and Dead Space: Ignition, a text-adventure for PSN and XBLA. Considering that these properties have been developed before the game, it should be interesting to see how the narrative between the games hold up.

Conclusion

Trans-media storytelling is inherently messy. Ideal fan fodder, but perhaps too much commitment for those of us out of the loop. Part of the issue with trans-media originating in the video games medium is the lack of foresight and planning in creating a universe from the start. Furthermore, the profit motive has often overrode narrative interests as the imperative for bridged storytelling. The results, some of which we’ve highlighted, are evidence of multiple industries still finding their feet in dealing which such a large task. Yet, as we’re seeing from the improvements from Resident Evil to Dead Space and now franchises like Red Faction where the developers are overtly declaring their intents to form a trans-media narrative (with approval of Jenkins, no less), trans-media storytelling is being taken more seriously. Certainly much more seriously than 15 years ago when video game mascots were being licensed out into comic books and other products without much added thought.

Metroidvania: A Comparison of Context and Design Implication

November 18th, 2010

“Metroidvania” is a stupid word for a wonderful thing. It’s basically a really terrible neologism that describes a videogame genre which combines 2D side-scrolling action with free-roaming exploration and progressive skill and item collection to enable further, uh, progress. As in Metroid and Koji Igarashi-developed Castlevania games. Thus the name.

Jeremy Parish on Metroidvania.

Metroid and Castlevania share a collection of remarkably similar mechanics and design elements which have lead to the term that I reference above, Metroidvania. The pair are similar games mechanically, but are covered in very different contextual wrappers. One franchise is a series of isolated space adventures, the other chronicles a family’s fight against the dark lord Dracula. There are many ramifications in the design that are born out of contextual necessity, leading into the core of these two games and driving a fork between them. Before we get to that though, let’s make a list of the basic properties at the heart of this pseudo genre.

- 2D platforming

- free-roaming nature (few restrictions on where to travel)

- emphasis on exploration

- a progressively expanding ability system tied to the exploration and combat

Castlevania tends to fluctuate iteration to iteration in regards to the ability and combat systems (Tactical Souls system, Glyph system etc.), but otherwise these elements remain fixed.

Differences

I’ve split the contextual differences into a range of key categories noting each game’s contextual obligation and then a summary of the differences in design that have arisen from it. As a clarification on what exactly I’m trying to get at, here is an excerpt of conversation that I recently had with blogging buddy Richard Terrell on the matter:

I don’t think that all of my examples have strong influences on the design (and you can tell as I didn’t back them up with examples). Rather I highlighted contextual constraints and then theorised a bit over what this means for the designing of the game. So, there’s not always a clear thread between what I say and what’s in the game, but instead there’s a connection between what I say and something the designers probably had to consider

Subsections

(Subsections are the areas branching off the main map, ie castle gardens, Tourian, Norfair)

Castlevania

- subsections correspond with the rooms of a castle (entrance, gardens, kitchen)

Metroid

- subsections correspond with alien worlds and the areas of inhabitants (elemental-themed areas, bases)

Outcome: Metroid games have a great deal of flexibility in the theme governing each subsection as the alien world context is quite broad. Nintendo do stick to a familiar elemental theme though as it’s a clean way to classify worlds and forms for interaction (lava crust platforms, destroying overgrowth).

In Castlevania there is relatively less freedom as the design of all subsections are limited to whatever constitutes a room in a castle. Players can therefore expect familiar room types to be present in every game, like the gardens, library and clock tower. Extending creativity beyond these constraints would only damage the credibility of the context. In order to avoid this inherent limitation, Portrait of Ruin introduced paintings that transport the player to different areas and Order of Ecclesia expanded the game out from Dracula’s castle to a fully realised world map system.

Abilities

Castlevania

- the protagonist gains abilities through specialised items and transformations

Metroid

- Samus gains abilities through her suit

Outcome: Samus has more abilities than her counterparts in the Castlevania series as there is only a finite number of upgrades that can be added to a human character before they essentially become less and less human. On the other hand, a powersuit exists inside the realm of science fiction which grants Samus a wide range of abilities from beams to morphballs and grapples.

If considered realistically, it’s quite strange that the protagonists in the Castlevania games can walk on water, float in mid-air and use their heads to bash through walls. There’s certainly an element of the supernatural appropriate to the horror context. The transformation mechanics, where the player takes the role of a various creatures, also draws on this part of the context.

Stringing

(Stringing is how the games draw the player from one area to another).

Castlevania

- strings the player with keys to doors, physically unreachable areas and some environmental hazards

Metroid

- strings the player with suit upgrades that assist in overcoming environmental hazards or unreachable areas

Outcome: Castlevania is varied in how it uses inventory and abilities to lead players to the next part of gameplay, however inventory items aren’t nearly as effective as new play mechanics when it comes to creating the “click” for players to follow. In Metroid, the player is only ever strung along by the interactions made possible through the powersuit. These interactions are embedded into the environment in the form of hazards and unreachable areas which make perfect sense given the volatile alien landscape. So, where Castlevania games often have a more limited primary ability set and thereby rely on more peripheral elements like inventory or character transformations to string players throughout the game world, all stringing in Metroid is accomplished through the interactivity granted by the powersuit. For the player it’s much easier to understand something through their own actions as opposed to static objects in a menu (keys and whatnot). This comparison is like comparing learning through reading a book as opposed to learning by doing.

Preventative Measures

Castlevania

- areas are locked from the player because they have been locked with a key, magical barrier or environmental conditions

Metroid

- areas are locked from the player because of environmental conditions

Outcome: We can see again that Castlevania uses a series of devices (magical barriers and environmental conditions) which work against the interactivity of the primary mechanics. In Metroid, almost all measures holding the player back (environmental obstacles such as heat pressure, underwater mobility, damaged landscape, large chasms) can be cleared by using the primary mechanics. Because Castlevania games have so few of these (player abilities), other, less interactive, means stand in as substitutes.

Land Formation

Castlevania

- land formation in castle interiors is generally box-like, outside is variable

Metroid

- all land formation is variable

Outcome: The majority of rooms in Castlevania games are fixed box shapes comprising the architecture of the castle. There are also common architectural elements in all Castlevania games, such as the staircase to the top of the castle and the clock towers. In Metroid, there are no geographic limitations to abide by besides a single room that has an open roof for Samus to lower her ship down into and save stations.

Enemies

Castlevania

- all enemies are regarded as Dracula’s minions

Metroid

- local flora and fauna compose part of the environment and enemy set

Outcome: Generally speaking, Metroid‘s enemies are more naturally suited to the landscapes because the creatures are contextually bound to the landscape. So, bats will live in caverns, creatures that live in firey areas can spit lava, obscure-looking enemies live in the dark world etc. The contextual connection in Castlevania isn’t as rigid. Enemies only need to abide by Dracula, mythology and horror contexts as well as the context of the respective room they’re situated in (evil dolls in a doll house, for example). This implication makes the enemies in Castlevania feel more like foreground elements, guests that have made their way into the castle and not regular members of it.

Protagonists

Castlevania

- the majority of Castlevania games feature different protagonists

Metroid

- Samus is the one and only protagonist

Outcome: The Metroid games must figure out new and inexplicably less believable reasons to rob Samus of all her gear at the beginning of the game. While Castlevania games can start anew with each entry and significantly change elements of the context (time period, character’s gender, backstory etc). Castlevania‘s narrative is something of a family legacy, where the story of Samus is a legend.

Conclusion

The comparison above highlights the way context dictates game design. Also clearly build a case against some of Castlevania‘s design decisions. This I wanted to intentionally explicate on as these properties were a sticking point throughout my recent playthroughs of Harmony of Dissonance and Aria of Sorrow. As a critical player of these two franchises, it’s the differences which stand out to me more than anything else. That is, what Castlevania does to Super Metroid is more apparent than the fact that Koji Igarashi-developed Castlevania games are Super Metroid variants. While I do criticise the series here, I do thoroughly enjoy these games. It’s just that they’re markedly inferior to the Metroid games.

I can’t go without recommending Gametrailers’ excellent Castlevania retrospective. The folks at GT to a killer job with these features, with lots of background research and good production values. Also stay tuned as I have a stack of Castlevania games which I haven’t yet played in my collection, so expect more analysis on this series in the future.

A Video Game Model For Teaching Debating

November 15th, 2010

The language centre I work at in China fields us teachers out to local schools as part of what I largely consider to be a marketing exercise in bringing more students to the school. For previous years the actual teaching side has been primarily stock language games there to fill the quota of time. The external classes were never really taken seriously and there wasn’t much effort by upper management or teachers to extend these classes beyond their transparent role as business pitches. Fortunately, in recent months, some of the senior teachers put together a new program and now we cover the skill of argumentation through weekly classroom debates. It’s certainly a big improvement and one of my favourite classes of the week.

The initial lesson is a teacher-orientated push through the basic debate structure with lots of scaffolding and puppetry of students as the teacher does their best to cover the basic structure through demonstration in a tight 40-minute time frame (as well as basic introductions). From then on, the kids have a one week reprieve, debating for every lesson thereafter. Students themselves are free to choose the topic while the local English teacher chooses the speakers and assists them in their speeches during regular lessons. After each debate (20 minutes or so), the foreign teacher provides a critique, gives advice and focuses on the topic for the week (presentation skills, rebuttals, etc). This model is followed for every lesson.

The idea behind the debates is that they act as a means to introduce the students to western ideology of reason as well as to improve their oral language and presentation skills. The latter 2 are important in bolstering the school’s reputation as a foreign language school for when some students will later participate in public speaking competitions. The former is a skill that they can’t get from their standard Chinese education and an important one to have as students in these schools are known to transfer to overseas high schools.

The fatal flaw in this design is the integration between the local and international teachers. Each speaker in the debate needs to speak for between 2-3 minutes, however students have been hitting on average 40 seconds and at the shortest maybe 8. Obviously, such short length compromises the teacher’s lesson and in fact their very presence. The bond tying these 2 sides together is that student’s performances in the debates will make up part of their English grade. Yet even with this measure in place, the local teachers have not been pulling their weight, as a result leaving students to write their speeches in their own free time (not even for homework!). As you can imagine, with Chinese students overworked as it is, this leads to a few sketchy sentences on a scrappy piece of paper come the beginning of class. This output by the students, while often great considering, is indicative of the lack of teacher support on their side of the fence.

Personally, I’ve tried to remedy this issue by providing students with supplementary materials which reinforce the structure of debates and the nature of rebuttals. Rebuttals are the trickiest part of the course as it demands that either the students think on their feet or pre-plan answers to possible points made by the opposition. Thinking on your feet is hard enough for a native speaker to do mid-debate let alone a speaker of a second language. And having the students consider the points of the opposing team in their own time before the debate is unfair given the lack of time allocated to debate preparation by local teachers.

As the classes carry on, the focal point for each class has moved away from basic presentation skills and into more finer points such as rebuttals, acknowledging weakness in an argument and using the floor time (audience participation) to your advantage. The tuition is now firmly on critical thinking and for this the students need more support. In order to push the students towards critical thinking, I’ve constructed a model designed to do 3 things: elaborate on ideas and reasoning, present the benefits of rebuttals to an argument and reveal how I calculate the winners of the debates. You’d be very much correct if you preempt me by assuming that the model is that of a video game. Below is my lesson plan/outline for teaching students about debates using video game systems as a model.

Debating Game – Lesson Plan

Preparation

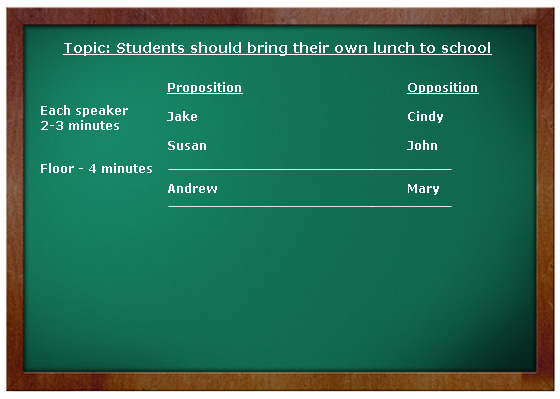

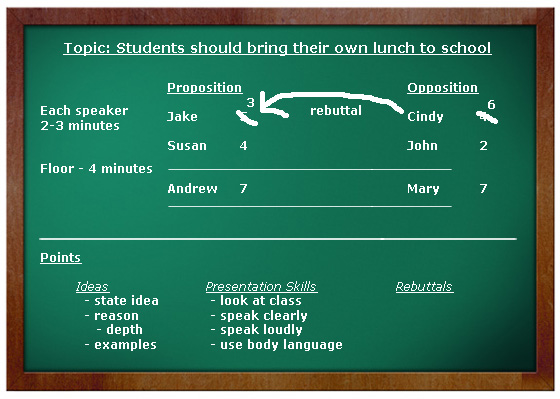

At the start of the class I elicit all the information in the picture below and write it on the board as such. This visual image gives the chairperson something to work from as well as informing the other students about the debate’s proceedings.

Setting the Context

(Teacher’s dialogue is in quotes)

“Who likes video games, raise your hand?”

“Cool, now in a video game what do you want?” (Answer: points)

“Well, a debate is just like a video game. So in a debate, how do you get points?”

The Finer Points of Ideas

(Students will likely make a few suggestions, try to steer them towards proposing ideas).

“You get points in 2 ways, the first is to say ideas. So….”

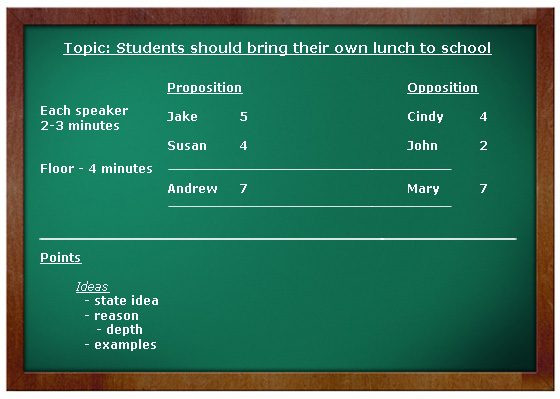

At this point I reference the team list I write up on the board before the debate and model examples based on the student’s performance. For the sake of the article, the topic of the debate is “Students should bring their own lunch to school”.

Elicit a point made by the first speaker of the proposition (Jake).

Elicit whether the proposed idea was a good one and how many points the students would give it. Ask the students how they get more points from a single argument/idea. Fill in this breakdown of an idea based on the students answers (may need to just explain this outright):

Idea

- state the idea

- reasons (why?)

- depth (reason linking)

- examples

Establish that each idea needs the above parts. The more of this supporting the idea, the more points the students get for the idea. “State the idea” is fairly straight forward, so too are reasons and examples. Do spend time to reaffirm this with the students by modelling with a proposed point (if the speaker’s point didn’t have reasons, examples etc, then elicit from students). By depth, I am referring to the way ideas link to reasons which link to more reasons which in turn link back to the main argument. For example:

“Students should bring their own lunch to school as each student’s food and dietary requirements are different – if students eat the food most suitable to them then they will be more healthy overall – a healthy school is a good school and will lead to better grades and a stronger outside reputation for the school – this will improve the lives of everyone at the school and is ultimately a good thing”.

Model another student’s proposed ideas (one with more reason, depth and examples) and highlight how this student would be rewarded more points. Write the number of points for next to each student. So far the board should look like this:

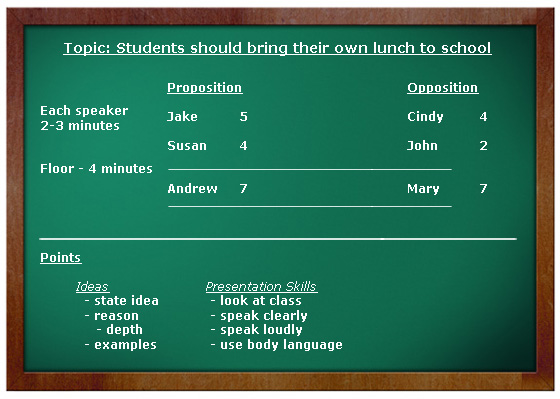

Reviewing Presentation Skills

“Now, there is another way to get more points, what is that?”

Students will probably mention presentation skills at which point write this on the board also under the heading “Points”. Quickly elicit a list of things that need to do when speaking and write this as a list on the board.

Rebuttals

(Students probably won’t catch on to the next point-scoring method, rebuttals, so just go ahead and take the lead).

“The other way to win the debate is through destroying the other team”.

Model the word “destroy”. You can do this by drawing an explosion on the board or pretending to break something in the classroom. I prefer the latter.

“So, how can you destroy the other team?”

(Students probably still won’t know, but let them try).

“You reply to what they say. Reply, what is a reply?”

Walk up to a student and ask “how are you?”. Let them answer and then say that their answer is a reply. That is, one person asks a question, the other replies. Drill the word “reply” orally.

Draw a line from the first speaker from the opposition (Cindy) to the first speaker on the proposition who you’d previously modelled (Jake). Tell the students that the opposition makes a reply and tell them the reply. For the sake of our example:

“Although students have their own dietary requirements, allowing them to bring their own food to school does not necessarily mean that what they bring will be ideal for their health situation. On the other hand, what the school provides covers the basic and most important nutrition for students.”

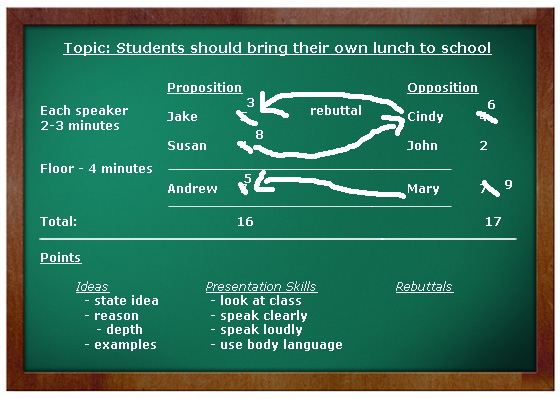

After this, ask the students whether they feel that the proposition’s idea that was replied to is now stronger or weaker. They should say weaker. Then remove a few points from the first speaker of the proposition and add a point or 2 to the first speaker of the opposition. Take another student’s point which had no rebuttal and get the class to think of a response to it. Once the explanation is over, write the word rebuttal under the arrow and drill orally. Add the word “rebuttals” to the list of point-scoring methods.

How the Teacher Chooses a Winner

Quickly draw in the rest of the points, briefly mentioning the ideas and rebuttals on either side, crossing out and adding points as you go (you can take what the students said in their debate and add if you need; if they’ve made good arguments then draw on them). Add all the points up and show a tally for either side. This demonstrates how the teacher chooses the winners of the debate.

Finally, the teacher can review, asking the students to recall the way to score points and score effectively.

Conclusion

If you read this blog then you know that video games are fantastic educators; they’d simply fail to be enjoyable and thereby sell if they weren’t. So all I’ve really done hear is presented debates as a game, incorporating the same devices that video games use to educate players and create goals (a running scoreboard, specifying player objectives and clearly highlighting the rules and means to win). Within this model, the trickier parts of the debate such as rebuttals, depth and reason are presented with much greater clarity.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99