A Video Game Model For Teaching Debating

November 15th, 2010

The language centre I work at in China fields us teachers out to local schools as part of what I largely consider to be a marketing exercise in bringing more students to the school. For previous years the actual teaching side has been primarily stock language games there to fill the quota of time. The external classes were never really taken seriously and there wasn’t much effort by upper management or teachers to extend these classes beyond their transparent role as business pitches. Fortunately, in recent months, some of the senior teachers put together a new program and now we cover the skill of argumentation through weekly classroom debates. It’s certainly a big improvement and one of my favourite classes of the week.

The initial lesson is a teacher-orientated push through the basic debate structure with lots of scaffolding and puppetry of students as the teacher does their best to cover the basic structure through demonstration in a tight 40-minute time frame (as well as basic introductions). From then on, the kids have a one week reprieve, debating for every lesson thereafter. Students themselves are free to choose the topic while the local English teacher chooses the speakers and assists them in their speeches during regular lessons. After each debate (20 minutes or so), the foreign teacher provides a critique, gives advice and focuses on the topic for the week (presentation skills, rebuttals, etc). This model is followed for every lesson.

The idea behind the debates is that they act as a means to introduce the students to western ideology of reason as well as to improve their oral language and presentation skills. The latter 2 are important in bolstering the school’s reputation as a foreign language school for when some students will later participate in public speaking competitions. The former is a skill that they can’t get from their standard Chinese education and an important one to have as students in these schools are known to transfer to overseas high schools.

The fatal flaw in this design is the integration between the local and international teachers. Each speaker in the debate needs to speak for between 2-3 minutes, however students have been hitting on average 40 seconds and at the shortest maybe 8. Obviously, such short length compromises the teacher’s lesson and in fact their very presence. The bond tying these 2 sides together is that student’s performances in the debates will make up part of their English grade. Yet even with this measure in place, the local teachers have not been pulling their weight, as a result leaving students to write their speeches in their own free time (not even for homework!). As you can imagine, with Chinese students overworked as it is, this leads to a few sketchy sentences on a scrappy piece of paper come the beginning of class. This output by the students, while often great considering, is indicative of the lack of teacher support on their side of the fence.

Personally, I’ve tried to remedy this issue by providing students with supplementary materials which reinforce the structure of debates and the nature of rebuttals. Rebuttals are the trickiest part of the course as it demands that either the students think on their feet or pre-plan answers to possible points made by the opposition. Thinking on your feet is hard enough for a native speaker to do mid-debate let alone a speaker of a second language. And having the students consider the points of the opposing team in their own time before the debate is unfair given the lack of time allocated to debate preparation by local teachers.

As the classes carry on, the focal point for each class has moved away from basic presentation skills and into more finer points such as rebuttals, acknowledging weakness in an argument and using the floor time (audience participation) to your advantage. The tuition is now firmly on critical thinking and for this the students need more support. In order to push the students towards critical thinking, I’ve constructed a model designed to do 3 things: elaborate on ideas and reasoning, present the benefits of rebuttals to an argument and reveal how I calculate the winners of the debates. You’d be very much correct if you preempt me by assuming that the model is that of a video game. Below is my lesson plan/outline for teaching students about debates using video game systems as a model.

Debating Game – Lesson Plan

Preparation

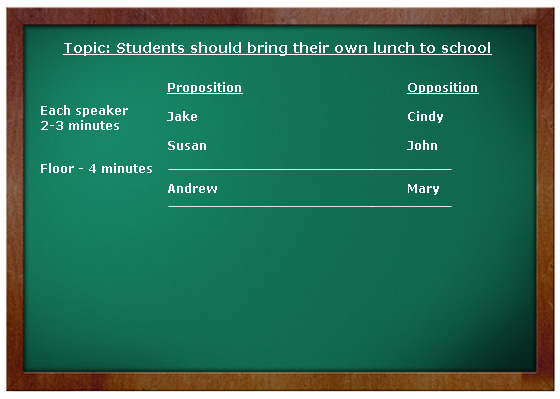

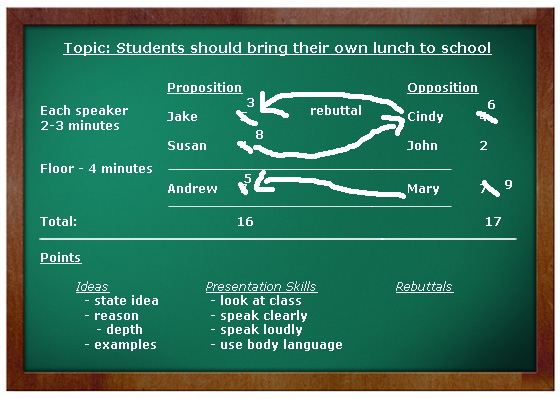

At the start of the class I elicit all the information in the picture below and write it on the board as such. This visual image gives the chairperson something to work from as well as informing the other students about the debate’s proceedings.

Setting the Context

(Teacher’s dialogue is in quotes)

“Who likes video games, raise your hand?”

“Cool, now in a video game what do you want?” (Answer: points)

“Well, a debate is just like a video game. So in a debate, how do you get points?”

The Finer Points of Ideas

(Students will likely make a few suggestions, try to steer them towards proposing ideas).

“You get points in 2 ways, the first is to say ideas. So….”

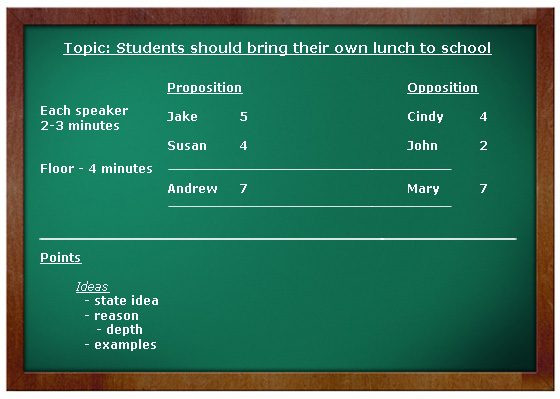

At this point I reference the team list I write up on the board before the debate and model examples based on the student’s performance. For the sake of the article, the topic of the debate is “Students should bring their own lunch to school”.

Elicit a point made by the first speaker of the proposition (Jake).

Elicit whether the proposed idea was a good one and how many points the students would give it. Ask the students how they get more points from a single argument/idea. Fill in this breakdown of an idea based on the students answers (may need to just explain this outright):

Idea

- state the idea

- reasons (why?)

- depth (reason linking)

- examples

Establish that each idea needs the above parts. The more of this supporting the idea, the more points the students get for the idea. “State the idea” is fairly straight forward, so too are reasons and examples. Do spend time to reaffirm this with the students by modelling with a proposed point (if the speaker’s point didn’t have reasons, examples etc, then elicit from students). By depth, I am referring to the way ideas link to reasons which link to more reasons which in turn link back to the main argument. For example:

“Students should bring their own lunch to school as each student’s food and dietary requirements are different – if students eat the food most suitable to them then they will be more healthy overall – a healthy school is a good school and will lead to better grades and a stronger outside reputation for the school – this will improve the lives of everyone at the school and is ultimately a good thing”.

Model another student’s proposed ideas (one with more reason, depth and examples) and highlight how this student would be rewarded more points. Write the number of points for next to each student. So far the board should look like this:

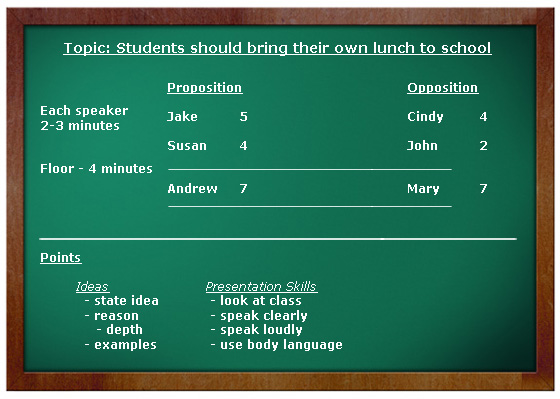

Reviewing Presentation Skills

“Now, there is another way to get more points, what is that?”

Students will probably mention presentation skills at which point write this on the board also under the heading “Points”. Quickly elicit a list of things that need to do when speaking and write this as a list on the board.

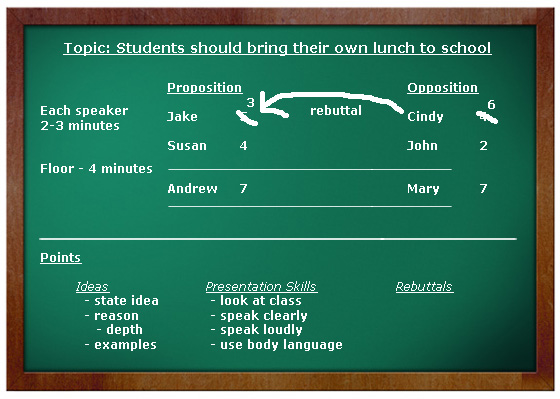

Rebuttals

(Students probably won’t catch on to the next point-scoring method, rebuttals, so just go ahead and take the lead).

“The other way to win the debate is through destroying the other team”.

Model the word “destroy”. You can do this by drawing an explosion on the board or pretending to break something in the classroom. I prefer the latter.

“So, how can you destroy the other team?”

(Students probably still won’t know, but let them try).

“You reply to what they say. Reply, what is a reply?”

Walk up to a student and ask “how are you?”. Let them answer and then say that their answer is a reply. That is, one person asks a question, the other replies. Drill the word “reply” orally.

Draw a line from the first speaker from the opposition (Cindy) to the first speaker on the proposition who you’d previously modelled (Jake). Tell the students that the opposition makes a reply and tell them the reply. For the sake of our example:

“Although students have their own dietary requirements, allowing them to bring their own food to school does not necessarily mean that what they bring will be ideal for their health situation. On the other hand, what the school provides covers the basic and most important nutrition for students.”

After this, ask the students whether they feel that the proposition’s idea that was replied to is now stronger or weaker. They should say weaker. Then remove a few points from the first speaker of the proposition and add a point or 2 to the first speaker of the opposition. Take another student’s point which had no rebuttal and get the class to think of a response to it. Once the explanation is over, write the word rebuttal under the arrow and drill orally. Add the word “rebuttals” to the list of point-scoring methods.

How the Teacher Chooses a Winner

Quickly draw in the rest of the points, briefly mentioning the ideas and rebuttals on either side, crossing out and adding points as you go (you can take what the students said in their debate and add if you need; if they’ve made good arguments then draw on them). Add all the points up and show a tally for either side. This demonstrates how the teacher chooses the winners of the debate.

Finally, the teacher can review, asking the students to recall the way to score points and score effectively.

Conclusion

If you read this blog then you know that video games are fantastic educators; they’d simply fail to be enjoyable and thereby sell if they weren’t. So all I’ve really done hear is presented debates as a game, incorporating the same devices that video games use to educate players and create goals (a running scoreboard, specifying player objectives and clearly highlighting the rules and means to win). Within this model, the trickier parts of the debate such as rebuttals, depth and reason are presented with much greater clarity.

Good Video Games and Good Learning Overview

March 2nd, 2010

After reading a Theory of Fun, many of the principles in James Paul Gee’s Good Video Games and Good Learning are likely already apparent: video games are inherently teachers of their rules and mechanics. In which case, Gee’s book, which further analyses how video games are a powerful education tool, is a fantastic continuing point if you’re a newbie to academic games studies (like me!). Gee explores how video games—or rather the situated learning in which video games offer—can be adapted to a classroom environment and provides thorough analysis of all facets of implementation. If you’re remotely interested in education alongside games then I can’t recommend this book enough.

It’s actually been maybe 6 months since I first read Good Video Games and Good Learning, so some of the core ideas have have meshed in with the words of other authors, but in any case, here are the more interesting ideas covered with my own ideas leveled in for good measure.

Games are Inherently All About Learning

Gee argues that games are deeply rooted in education. After all, games are simply a system of rules (like the laws of the universe) that create a simulation (reality) in which mastery (education) is the intention. Without learning the basic rules, continual practice and eventual mastery one cannot complete a game, unless that game is too easy and therefore unengaging. Therefore, at the heart of every game is education.

Situated Texts

Games are texts (think textbook) in which the player (student) is situated within and the rules (formula) are externalised. In science, sociology, maths and other subjects you learn about the invisible rules which govern your world, in video games, these rules are no longer invisible, but made explicit (think of how rules are embedded into the design of the game world visually, aurally and through agency).

Schools are Giving Kids a Manual and Asking them to Learn

For this point, Gee often discusses his experiences with the first-person RPG Deus Ex, in which he initially read the game’s manual and thought it was too hard. It was dense with information, just like a text book. A glossary of specific terms which are interlinked, a complicated keyboard layout, multifaceted functions which changed depending on certain situations, variables obeying a set criterion. Gee says that he did what any kid would have done and just started playing. Hours later Gee returned to the manual and understood most of its content because he’d learnt by experience. In which case he only needed to use it for reference; the same way a text book ought to be used.

Schools, Gee argues, are giving kids the manuals (text book) and asking them to learn for themselves, in an environment that doesn’t effectively cater to their personal needs and issues (see next heading) where the rules are unclear. In video game, the rules are easy to learn because they’re a part of your experience and if the rules aren’t taught properly, the game isn’t very successful.

Games Provide a Variety of Information in Different Forms Right When the Player Needs it

Gee makes many claims about video games being effective educators and fortunately he provides a wonderful evaluation of the RTS game Rise of Nations to evidence his argument (as a player though, you’ll likely start think of examples yourself as you read). In Rise of Nations, like any well designed game, information is delivered to the player in different forms. Information is delivered visually, aurally and/or through on-screen text cues as the player approaches the exercise. Information is also given based on agency, if the game notices the player is playing incorrectly, they will advise the player on how to play correctly. Furthermore, the player can also consult the physical manual, look online for a guide or engage with external fan sites. This is all unlike a classroom where help is limited and teacher support enqueued up with other students. Video games provide the player with information right when they need it. Instant feedback results in faster, more effective education.

Games are clearly doing something right

Contrast for a moment your experience of learning in school and your experiences of learning within a video game. Games are fun and engaging for players, school is often disliked and unengaging for students. Education is central to both. With this notion in mind, Gee argues that video games are clearly doing something right in which most schools are not, therefore it’s worthwhile to investigate how video games are successful educators.

Passion Communities are superseding traditional education

You’d think that what Gee is advocating is to replace the pen with a controller and the textbook with a video game, however this isn’t it. Video games create an environment which works well for education, Gee is interested in recreating this environment within the classroom. As also explored by Henry Jenkins of MIT, popular culture and the internet actually provide an already existing framework for this new form of education, it’s call passion communities and its education is already exceeding the institutions.

Passion communities are groups of people who have a shared interest and together participate in activities which nurture their interest. Think of any fan site community which produce fan-related material such as graphics, music, translations, writing, podcasts and you get the idea. Many of these communities reside on the internet and maintain very high standards of production (see Convergence Culture for many examples). This blog is part of a passion community, and unlike in school:

- I’m aware of what the standard is (I read other blogs too, you know) since it’s set by the community – in school work is kept to oneself and the standard is unknown until you’ve handed up several assignments, the students grope around in the dark in the meantime, producing misguided work

- And as part of this I can access and learn from the work of other bloggers (students), including referencing their good work for information – in school, only academics, the teacher or the textbook ever have the correct information

- There’s great freedom in the content I produce and the way I produce it (and ultimately the direction I wish to learn), I can focus on a broad range of issues or mine deeply into a single topic – in school you are forced to learn pre-designated material at a pace set by the curriculum

- I feel a sense of authorship because of community recognition – in school it is difficult to find recognition because work is not shared

- I receive immediate, useful feedback from a group of different people, with different backgrounds through the site or different mediums such as Twitter, MSN, Skype and other networking services – in school there is just a teacher with a grade and maybe half-hearted marking

- I can co-operate with other people or work together on a project within a community, I also get to choose who I want to work with – in school this is decided upon by the teacher

- Resources are shared and readily available – resources come from the library and only one person can borrow a book at a time

- I can reference material anytime I want – at school, referencing only begins in the later years

About adopting a role, learning a doctrine

The question of what we learn in a video game is crucially important and Gee answers this surprisingly well. I mean, how can the rules of God of War stack up to the thoughts of Plato? Gee believes that because we co-author video games, that is, we inherit the avatar while maintaining our own identity, we therefore inherit the respective doctrine that comes from the avatar’s occupation/role.

If I remember correctly, Gee references Supreme Commander, where he discusses the way the game’s mechanics force the player to adopt the principles of a soldier by working as a team and obeying a strict set of playing requisites. This doctrine, Gee says, pertains to all parts of the game, from the way your instruction are given and objectives presented, the realistic graphics and even in the wording of the instruction manual. You are constantly forced to act with the responsibilities of a respectful soldier.

Other titles also teach the doctrine of their avatars. By playing Splinter Cell; you see the world in a series of darkness and light, Resident Evil; in conserving ammo and avoiding danger, Guitar Hero; playing a song accurately and titling the guitar head to be a rock star, Tetris; spatial awareness.

Pleasantly Frustrating

I quickly discussed this concept in DP’s Games Crunch 2009 Part #2. Although, if you’ve played games for any amount of time, you’re probably already familiar with the idea: games that are frustrating because they engage our interest and test our abilities in ways just outside of our reach.

The Education Crisis – India and China

This is quite interesting. As China and India out rote-learn western kids in our current industrial revolution-based education system, we’re presented with a crisis. Innovation in education is the antidote which can keep western countries competitive and this is why a new education system is so important and why video games are worth a look.

Parents and Critical Thinking, the teacher takes role as a mentor

With the internet and all this new software which can provide accurate, precise information instantly, the conventional role of teachers as the possessor of all knowledge just doesn’t work. Teachers can’t beat Wikipedia or Google, education wants to become communal but the system doesn’t allow it. In which case, teachers (and parents too) should act as mentors, facilitating the means for kids to critically engage in their learning.

Conclusion

I think that’s most of it covered, albeit pretty quickly. All the points I’ve made here are explored in great depth and with solid justification in Jim Gee’s book, so I strongly urge you to hunt down a copy of Good Video Games and Good Learning and read it yourself. I have quite strong feelings towards education and this book really hits on some important topics which are worth considering.

Additional Readings

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99