An Overview of Trans-media Storytelling and Video Games

November 21st, 2010

Sonic The Hedgehog: Triple Trouble is a once-off collectors edition comic, part of Archie Comic’s long-running line of Sonic comics which my news agency imported from the states during the mid-nineties. It was also, thanks to some convincing from a friend, my very first comic. After Triple Trouble, I bought another 6 issues before my quiet country town newsagent stopped stocking the line altogether, effectively killing off my interest in comics with one fellow swoop.

Skip forward to the end of last year and my brother is placing an order through Amazon on my behalf for 3 of Alan Moore’s esteemed graphic novels; my interest has re-emerged. Having thoroughly enjoyed the selection of imported comics, I walk into Adelaide comic book store Pulp Fiction Comics in search for the next series to invest in. Yet despite still being a self-confessed comics newbie, the trans-media pollination ensures that the environment isn’t an unfamiliar one. World of Warcraft, The Legend of Zelda, Dead Space and Prototype are just a sampling of the familiar brands I see on the store shelves. As I walk through the store, trying to gain ideas, my mind drifts back to Sonic and I’m reminded of the trans-media connection which has always existed between games and comics.

Trans-media Storytelling: A Definition

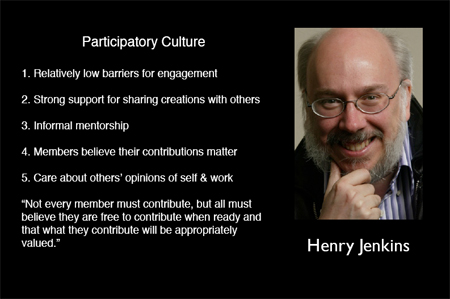

Trans-media storytelling is a concept first put forward by academic Henry Jenkins in his book Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide to define storytelling told over multiple forms of media. The crux of the idea is that each form of media supports the others and provides the reader with different, medium-specific viewpoints in which to interpret the text as a whole. Naturally, these types of texts are rich in content and artistic styles, commanding a dedicated user base who are required to spend more money to invest in the entire narrative web. In this regard, building a trans-media franchise is like building a universe.

With consumers accessing their news and entertainment through a range of different avenues (physical purchasing, iTunes, Netflix, Gamefly, RSS feed) on a range of different platforms (mobile phone, TV, MP3 player, game console, PC) it’s become more difficult for news and entertainment companies to commodify their target audience. Their markets are fragmenting due to the enormous amount of choice that new technology has given consumers. Establishing, or extending out to become, a trans-media franchise is therefore a successful way to connect audiences spread over various avenues and mediums, therefore reclaiming corporate control over the market. As can be seen by the likes of The Matrix, Twilight or Pokemon, the financial payback and consumer loyalty in these investments are worthwhile. In this regard, building a trans-media franchise is like building the next phenomena.

Two Points of Contention

And here we hit an enormous point of contention: how do we distinguish a trans-media franchise from a series of adaptions? Well, adaptions, say that of a comic to a video game or a book to a film, do not necessitate reading and interpreting texts over multiple media—and thereby through the lens of each respective medium—as there is no fragmentation. It’s all the same story, just in different forms. Franchises which use this approach to storytelling are what we’d call a media franchise and they constitutes the majority of cross-medium production. Scott Pilgrim which has had its narrative adapted from a comic book to a movie and video game is an example of a media franchise.

The Matrix, however, is a trans-media franchise as Enter The Matrix, The Animatrix and the anthology of comics all support the viewing of the films by providing context on characters and backstory. Consumers who only watch the movie are given a rather abrupt introduction to characters like Niobe and Ghost in The Matrix: Reloaded who first make their appearance as protagonists in the game Enter the Matrix. In fact, this aspect was a point of criticism for movie critics, yet fans who’d played the game didn’t find the introduction to be jarring at all. The Animatrix, particularly The Second Renaissance Part 1 and Part 2 shorts explain how the world as we currently understand it was overtaken by machines. These parts of The Animatrix, as an example, give credibility to the origins of the series as layed down in The Matrix and support the ideologies in the characters in Zion prevalent in Matrix: Revolutions. Just by these few examples, we can form an understanding of the narrative complexity at work. In this sense, trans-media franchising is the process of creating a universe or a phenomena, whereas media franchising is about transferring one narrative to other mediums.

A Case Study (Past-Present): Resident Evil

There are a number of key video game franchises which have evolved into trans-media franchises (Final Fantasy, Super Mario Bros.), but, hindering the definition, also include straight out adaptions as part of their cannon, making it difficult to classify these franchises into one school or the other.

Let’s use Resident Evil as a model to better understand this dilemma. There are Resident Evil games, books and films, with the games forming the central narrative. All of the books bar two (Resident Evil: Caliban Cove and Resident Evil: Underworld) are based on the video games. Resident Evil: Caliban Cove and Resident Evil: Underworld support the events from the video games since they are side stories which flesh out the role of Rebecca Chambers and the Umbrella corporation respectively. However, several of the books (both adaptions and side stories) contradict details made within the video games (the location of Racoon City is often confused, for instance).

The relation to the films are equally complicated. Capcom claims that the live-action movies aren’t canonical, however story elements from the movies have found their way into the video games (thanks Cavia!). For example, Red Queen from Resident Evil (movie) was adapted into Resident Evil: Umbrella Chronicles. Furthermore, the recent CG film Resident Evil: Degeneration officially ties together the narrative threads between Resident Evil 4 and 5.

Even within the video game medium, the fundamental plot is still a bit of a blur. Side stories (Umbrella/Darkside Chronicles, Outbreak etc.) reference the plot of the main games, but rarely do the main games reciprocate the citations. This loosens the strings between each production, effectively illegitimising the credibility of the side narratives.

Since Resident Evil was never originally intended to be a franchise spanning multiple media, and such expansion has seemingly been driven by the profit motive, Resident Evil’s narrative has become severely mangled over the years. Alas, despite the messy story, I think it’s fair to claim that Capcom have created a universe with this property, which makes it one of gaming’s early and more significant trans-media franchises.

Awkward Growth

Resident Evil is unfortunately a pretty typical example of expanded narrative, or rather, the milking of a franchising for extra capital. For trans-media narratives to work properly keen commitment is required on behalf of publishers. It is a much better idea to begin with the intent of creating trans-media property and then acting on this principle. On the other hand though, creating an expansive narrative over several mediums is a risky proposition. Usually it’s only at the point when mass success is realised that introducing other media becomes a priority—even though the threads for added narrative haven’t been layed. The next game is an example of a production where the decision to become trans-media was made too late in the creative process but before the release of the initial product. That is, a step between a Resident Evil and a trans-media franchise built from the ground up.

A Case Study (Present): Dead Space

Although it has dissolved into a confused narrative mess, Dead Space is an example of a more genuine attempt at crafting a trans-media franchise, having decided to become trans-media from the outset. The problem with Dead Space though is that the original game was scripted before the 4 prequels which have subsequently preceded it and therefore the core narrative doesn’t acknowledge the later prequels. As a result, it’s hard to care much for the continuity without the narrative references to keep it in place. Furthermore, each of the prequels tell fairly similar tales of survivors trying to escape from the effects of the Red Marker, only the recently released novel, Martyr deviates from this clichéd perspective.

With Dead Space 2 set it arrive later this year it seems that EA are willing to keep this trans-media thing going with a new graphic novel Dead Space: Retribution and Dead Space: Ignition, a text-adventure for PSN and XBLA. Considering that these properties have been developed before the game, it should be interesting to see how the narrative between the games hold up.

Conclusion

Trans-media storytelling is inherently messy. Ideal fan fodder, but perhaps too much commitment for those of us out of the loop. Part of the issue with trans-media originating in the video games medium is the lack of foresight and planning in creating a universe from the start. Furthermore, the profit motive has often overrode narrative interests as the imperative for bridged storytelling. The results, some of which we’ve highlighted, are evidence of multiple industries still finding their feet in dealing which such a large task. Yet, as we’re seeing from the improvements from Resident Evil to Dead Space and now franchises like Red Faction where the developers are overtly declaring their intents to form a trans-media narrative (with approval of Jenkins, no less), trans-media storytelling is being taken more seriously. Certainly much more seriously than 15 years ago when video game mascots were being licensed out into comic books and other products without much added thought.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99