How Super Mario is a Great Crash Course for Games

October 24th, 2009

Now to conclude my three part series on Super Paper Mario. There’s actually been a nice progression between articles, so do allow me to once again regurgitate:

How Super Paper Mario Doesn’t Feel Like Work

Super Paper Mario is about utilizing a palette of game modes to reach a certain means. Each of these “modes” is minimalist and presented in a structured way which doesn’t make the game as a whole feel like arduous on the player.

How Super Paper Mario Feels Gamey

Each of these “modes” are influenced by styles and genres from other games, this makes Super Paper Mario feel very game-y. That is, you’re managing a series of gameplay styles derived from other games to win the game of Super Paper Mario, giving Super Paper Mario an inherently game-y vibe to it.

And this time: How Super Mario is a Great Crash Course for Games

This argument will be very short and simple this time as much of my previous discussion has already borderlined on this argument. Super Paper Mario is a fabulous hybrid of different styles taken from different genres of plays. To complete the game, the player must form a mastery of these different styles and co-ordinate them together to solve the fundamental challenges that the game presents. This entails that the player have a thorough understanding of the workings of each play style and what separates them apart, so that they can match them together in a way that smooths the bumps between them. In terms of the theory it teaches, Super Paper Mario acquaints the player with the basics of popular game genre, particularly from traditional games such as Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda and games of the Metroidvania genre. In which case, Super Paper Mario is an ideal crash course on the basics of video games.

In doesn’t just end there though. The lore of the game itself is also very important, and Mario’s universe is one of the industry’s richest and longest-standing. The villagers of Flipside and Flopside (the game’s central hubs) aren’t your typical Nintendo characters though, which, in some respects pokes holes in this argument. Much the same to the antagonists which are all new to the series in this iteration of the sub-franchise.

One last point: The game’s fantastic writing draws a great deal of influence from not just the world of Mario but also from other Nintendo properties and the wider nerd and gamer culture as well. Their integration is often very subtle, but very clever as well. You can find a list of such references here under Similarities and References to Other Games. Furthermore the video below provides a classic example of the cultural integration of video games into the writing and dialogue. It’s a spoof off of Japanese dating sims, by the way:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wApWFddgvoY

I guess what I’m trying to say through all this is to get your kids onto Super Paper Mario as it’d be a good way to jump start their interest in the medium.

How Super Paper Mario Feels Gamey

October 22nd, 2009

Super Paper Mario is about utilizing a palette of game modes to reach a certain means. Each of these “modes” is minimalist and presented in a structured way which doesn’t make the game as a whole feel like work.

This time my argument is simply that:

Each of these “modes” pull from a melting pot of different styles and genres of other games. If we pool this and the above idea together, I mean to say: you’re managing a series of gameplay styles derived from other games to win the game of Super Paper Mario, giving Super Paper Mario an inherently game-y vibe to it.

Super Paper Mario is a rich tapestry of different rule sets plucked from a broad range of games. So let’s talk directly about said influences and how their qualities are pertained in Super Paper Mario.

Super Mario Bros (2D Platforming)

You can derive this much from the game’s title alone. Super Paper Mario is an obvious throwback to the original Super Mario Bros. in its primary design as a 2D platformer. Even some of the initial stages mimic the original’s level design with a nod and a wink.

Super Paper Mario runs at a slower pace though, and fits neatly into the exploration style of Mario platformers such as Yoshi’s Island. Characters don’t really sprint or gain much momentum, jumps are always short and usually offer little platforming challenge. The divergences from the original are a result of equalizing the game with the RPG and puzzle elements. Much of the puzzling and exploration comes from the dimension flipping, yet flipping dimensions in a fast paced Mario platformer would only act to slow the game down and interrupt the flow.

The 3D platforming sections are generally quite barren and slow to walk around in, so the majority of the player’s time is spent playing the game as a traditional platformer. Mushroom power-ups, the Wii-mote’s layout similarities with the NES pad, world-stage (ie.8-1) level division and a player score also makes for good comparison.

Paper Mario: The Thousand Year Door (Context)

Paper Mario: The Thousand Year Door is, as much as the original Super Mario Bros., imperative to Super Paper Mario‘s design. It’s a significantly contextual influence and to a lesser extent mechanical. Many of the assets are directly taken or heavily derived from Thousand Year Door, as well as the quirky humour of the narrative and general vibe of the game.

Crash Bandicoot (Forward running 3D Platforming)

On it’s side Super Paper Mario bears a crazy resemblance to the Crash Bandicoot series. It’s kind of ironic when you consider that once Super Mario 64 was released, Crash received major criticism for not being a “proper” 3D platformer. Mario kinda waltzed in and crashed the Playstation party—at least until people finished Super Mario 64 and wondered what else they could play—and now Mario is totally ripping on Crash’s style. Don’t Nintendo have any dignity?

The forward running in Super Paper Mario is a stifle bit weird simply because Mario must be seen flat on the screen, therefore when he runs forward (as by the perspective) he kind of runs to his left (as by his flat character model). Whereas in Crash Bandicoot, Crash always faced forwards and ran away from the screen, which made a lot more sense. Both of them suffer from the same problem of not being able to clearly judge the distance of gaps.

Echochrome (Puzzling)

By referencing Echochrome what I mean to say is that some of the puzzles require you to manipulate perspective to open and close pathways which you can travel across. For example: switching into 3D to cross a bridge which isn’t foregrounded in 2D or switching into 3D to enter an area infront of the character. Both games require the player to think beyond the visual illusion or to create their own.

Wonder Boy (RPG)

Structurally Super Paper Mario is similar to the Wonder Boy series in that they are both My First Metroidvania kinds of games, with lite RPG elements sprinkled over a platforming base. Characters have a health system and must make their way through a rather simplistic world.

Zelda (RPG)

The pixl ability system is akin to the Zelda inventory system where new items are gained and then integrated into the game’s progression design. The earlier stages play to this structure well, but eventually Super Paper Mario doesn’t do as much to tutorialize the new abilities within the environment. Carrie and Fleep in particular are underutilized and aren’t very well integrated into the game.

Others?

As you can see Super Paper Mario internalise many design ideas from other games to create it’s own. Some of them are crucial to the game’s identity such as Super Mario Bros., others are more coincidental similarities such as Wonder Boy or Echochrome. Super Paper Mario requires the player to master the skills of these different games and then co-ordinate the different styles together to ultimately complete the game. For example, the player must switch between Super Mario Bros. and Crash Bandicoot style of play to solve a perspective problem which is very Echochrome-like in nature. It’s this overaching design which link the various styles together that gives Super Paper Mario an unmistakably game-y vibe to it. The previous games were very much a celebration of the Super Mario phenomena, in which case Super Paper Mario casts its net wider as a celebration of many different game styles and genres.

I’m sure there are other titles which I’ve missed out on here, do any come to mind? Please let me know in the comments.

Next Up: How Super Mario is a Great Crash Course for Video Games

Additional Readings

Mario & Luigi Interview: Bihldorff’s Inside Story – Retronauts

(Good insight into Treehouse’s localisation process)

How Super Paper Mario Doesn’t Feel Like Work

October 20th, 2009

(Just a quick divergence from the Metroid discussion for those of you wanting something different.)

If you zip around the gaming side of the blogosphere for a while, you’ll notice that a lot of man-child bloggers (I’m 21, still haven’t quite graduated into that role yet) complain about the increasingly high barrier to entry of many current generation games. The entry price of familiarizing yourself with a complex, fatigue-inducing system of rules is often too steep to be considered leisure—it feels like work.

It’s an understandable qualm. I notice it myself when choosing the next game to play from my shelf. Suddenly length and accessibility have become determining factors of my consideration set, rather than personal preference (ie. the thought: “I feel like this kinda game”). Games require commitment and it’s difficult to dedicate yourself to finishing something that feels like work.

It’s not really about scope or difficulty, but rather baggage. Players don’t like to be burdened with unnecessary weight. For instance, an RPG which requires the player to buy, equip, unequip and sell their gear in a rotisserie-like fashion every time they arrive at a new township. Such sub-systems for many games are often mandatory components of the main quest and must be managed in co-ordination with the rest of the game. From the perspective of players such tasks can become menial, the rewards are measly and the effort in participating therefore seen as unjust. When these layers of weight amount, the game in its entirety can seem not worth the effort.

There’s an easy workaround for this problem and you’ve probably already figured it out: remove the dead weight. By doing this a developer can take a “high commitment” game and streamline it into a lighter product without skimping on the scale or sophisticated. I call it designing through deception. Reward the players with the perks from what is generally perceived to be a “high committal” game, offer them the depth and sense of scale, but remove the hard labour. We’ve become fussy over the years and our hobbyist nature requires cushioning.

Many portable games are pretty damn good at nailing this philosophy, which is to be expected given the properties of the medium. Console games are slowly starting to bend this way of thinking too. Nintendo really get it. Take Mario Galaxy as an example. Mario Galaxy can be played in short bursts or for marathon durations. Mario’s techniques are simple, there are no permanent upgrades, instead progression is embedded in the level design. There is only a single stream of skills and they require no maintenance, just mastery and technique. This player-centred approach lowers the barrier to entry without losing the sense of scale of a larger game and still rewarding the player quite frequently.

Super Paper Mario

A few weeks back I completely breezed through Super Paper Mario. I’d spent a week of my holidays cruising right on through to the end. It’s a game that I felt strangely comfortable with and as a result could dip in and out of play without that foreboding feeling of “I’ve started this game, so now I have an obligation to finish it”. It’s a game that embodies much of this design philosophy.

Super Paper Mario is actually a pretty sophisticated game though, as in it has many parts. I mean, it’s got platforming in two different dimensions, party management, inventory, abilities and side quests—that’s pretty wholesome right? It probably seems like quite the burden then, but isn’t. The trick is that Super Paper Mario manages to allude the player with the way its system is organised and presented. It does this in three ways: streamlining each “mode” of play to its fundamentals, clearly sectioning off different modes of play and only allowing the player to operate in a single mode at the one time. Let’s take a quick look at these different modes of play individually to see how they achieve this desired effect.

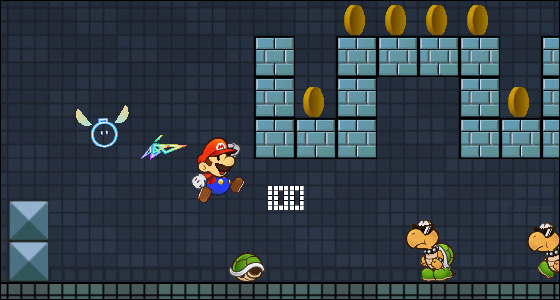

Platforming

The most obvious example would be the platforming. Both the 2D and 3D platforming are relatively simple. Although the platforming is practically lifted straight from the original Super Mario Bros., the difficult never reaches anything beyond, say, level 3-1 in the original game. Enemies only take little damage from your health bar, bottomless pits are few and never wide enough to stop you in your tracks. Mario and company can’t even build up much momentum. Only the brothers can gain enough to leap one block higher which isn’t saying terribly much. The platforming is simple and doesn’t require too much attention, it basically works as the medium for everything else (the exploration, mild combat and puzzling) to operate in.

There are two modes of play here, the 2D and the 3D platforming, and the only difference between them both is the change in perspective which in turn covers and hides different parts of the stage. Flipping, as the game calls it, is done frequently but only requires a simple press of the ‘A’ button and occurs almost instantaneously. The player doesn’t need to learn any additional techniques to operate in either dimension. Players only play in one dimension at a time and Mario is the only character who can switch dimensions.

Party Management, Abilities and Inventory

Another example would be the inventory, abilities and party management systems. Collectively these systems are quite complicated, but individually they’re rather simple.

Party

The player takes on 4 different party members each with a handful of specific properties. For instance: Bowser takes less damage, can deal more damage, is a slower walker, is larger and more difficult to more around in tight areas and can breath fire. This might seem complex but actually each character fits a gameplay archetype. Mario for platforming, Bowser for offensive attacks, Peach for long distance travel and Luigi for vertical jumps. It’s often very clear which character is suitable for which situation. Considering Mario has the ‘flip’ ability, players will use him for the majority of the game.

Abilities (Pixls)

Over the journey the player acquires 8 different pixls each with their own ability such as turning into a bomb, platform or hammer. Again, very simple, each one has just a single function.

Inventory

A series of items which can heal, take damage, add properties to party members and be traded and used in sub-games. The player has a tight limit on the number of items they can carry at the one time.

As with the dimension swapping, these systems are cleanly packed away from other parts of the game. For general use the player will access these three systems through the quick-use menu, a horizontal drop down menu which allows selections to be made on the fly. Whereas ‘A’ was used to switched between the binary 2D or 3D selections, the quick-use menu actually houses three different “modes”. To enter the quick launch the player must pause the game, cleanly separating these modes from the others.

Side Quest Options

Lastly there are side quest items such as cards, recipes and maps which are presented vertically on the menu screen. These cannot be reached via the quick-use menu, separating themselves from the rest.

Conclusion

As we can see, Super Paper Mario is collectively a rather sophisticated game which features two flavours of platforming, party management, a series of abilities and plenty of side quests. Yet at the same time each part is streamlined to it’s minimalist, and separated from the other modes of play by menus and buttons configuration. The player is only concerned about a small number of variables at a single time, often being the lite platforming, respective pixl equipped and the character they have chosen (more often than not Mario). Considering that the game is never designed to have the player frequently swapping out their characters, using items or switching pixls, the core part of play revolves around the platforming with moderate use of other aids for exploration. It’s very straightforward, and compacts it’s complexity, unpacking itself where needed. This makes playing Super Paper Mario very light weight and burden-less as the gameplay is presented in a way that never feels any more complicated than a simple platform game. In actuality though the player often resorts to peripheral mechanics, co-ordinating the different systems together to reach a desired outcome.

Next up: How Super Paper Mario Feels Gamey

Additional Readings

Super Paper Mario Interview – Gametrailers

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99