Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros. – The Limitations of RPG Overworlds

May 1st, 2018

“Compared to previous games in the series, this one has a lot of volume. A lot of people said they wanted more to play in the third game, so I definitely wanted to increase the volume a lot for the next one.”

Akira Otani, game producer of Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros.

Akira Otani and AlphaDream’s aspiration to increase the game volume of Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros. is perhaps best summarised by the data below taken from How Long to Beat, a play time aggregate website based on user submissions.

Superstar Saga – Main Story: 18.5 hours Completionist: 27.5 hours

Partners in Time – Main Story: 18 hours Completionist: 37 hours

Bowser’s Inside Story – Main Story: 22.5 hours Completionist: 35.5 hours

Dream Team Bros – Main Story: 40.5 hours Completionist: 60 hours

NB: The play times on the site are constantly changing due to new submissions, so these times were captured at the time of writing.

As you can see, Dream Team Bros. is as large as the previous two games combined. The question is, where does the extra 20 hours of gameplay come from? Unfortunately, answering that question would require a massive amount of data on how long players spend in particular sections of the game, which isn’t so feasible. Based on my own experience with the Mario and Luigi series, I would argue that the following factors contributed significantly to Dream Team Bros.‘s extended play time:

- the new Luiginary Works mechanics and their respective level challenges which bulk up the sidescrolling gameplay

- the larger map sizes which increase the time spent in the overworld

- the expanded swarms of peon enemies which extend the duration of battles

The influx of peon enemies create more spatial and strategic gameplay (which is covered further in Adventures in Games Analysis). However, they can protract the length of battles if the player doesn’t pay attention to the specific group AI patterns and exploits these weaknesses. Then again, the same can be said of the core action-reaction interactions as well.

For the purpose of this article, I’m more concerned with the increased amount of time spent outside of combat as these sections—like in most RPGS—are the less interesting parts of the game. Whilst games should include gameplay of varying levels of intensity (with combat, in this case, being the most intensive), Dream Team Bros.‘s forty-hour play length only makes the minimal gameplay outside of combat more apparent. This is particularly the case for the dream world challenges, which constitute a significantly larger portion of the gameplay mix than in Bowser’s Inside Story. But why exactly are these areas of the game so lacking in the first place?

Overworld

The isometric overworld gameplay benefits from the basic dynamics of space and the limitations of the camera perspective. The camera only captures the area directly around the Bros. and so the player needs to move around each environment to trace the outline of each room and mark points of interest in their short-term memory. Once the player has enough knowledge of their surroundings, they can make an informed decision about how to engage with the particular challenges of the room. This simple form of cartography provides the most basic form of engagement on the overworld.

As the player moves around and checks items into their short-term memory, they’ll probably put enemies at the top of their mental checklist. Similar to the Zelda games, enemies populate the Dream Team Bros.‘s overworld and persuade the player to move in particular ways. However, the overworld is not tightly tuned around these interactions. When contact with an enemy instantly warps the player into a battle which can last several minutes at a time, the developers don’t have many options for increasing the richness of these interactions without skewing the game disproportionally towards combat. So in balancing the consequences of touching an enemy on the overworld, the developers give the player enough space to slip past their foes without too much trouble.

Further to the points above, the camera and jump mechanics simply cannot facilitate the act of subtly avoiding enemies in space. Even with the stereoscopic 3D screen, the isometric camera perspective inherently has difficulty communicating the distance between bodies in space. Luigi, as a trailing partner, also collapses the space around the player.

Tying simple cartography and avoiding enemies together, puzzles pave the player’s path to progression. AlphaDream designed the majority of puzzles around the Bros. out-of-battle techniques, such as jump, hammer, and ball hop. Unfortunately, even though the player can usually use these abilities on a wide range of game elements, the mechanics lack the dynamic qualities and nuances necessary to facilitate a variety of engaging puzzles. With so little complexity to work with, the Bros.’s abilities usually function as little more than keys to locks and most puzzles revolve around the player using their various keys to activate switches in a particular order so as to access a new area.

Being a Mario and Luigi tradition, AlphaDream baked in various collectables into Dream Team Bros.‘s overworld, namely beans. In Bowser’s Inside Story the player, as Bowser, explores the overworld map and comes across bean holes which they cannot uproot. Since these bean holes are hidden in plain sight, players have to store their locations in their short-term memory for several hours until the Bros can make it out to the overworld and uproot them. When the Bros. do escape, the player can explore the overworld from whichever direction they wish, and so the order by which the player recalls the locations of the beans is very organic and player-driven.

In DTB, beans add an observation element to exploration. However, the game lacks the dynamic memory suspension twist of BIS as the player can collect the majority of beans on their first pass through an area.

Although the overworld contains a small set of diverse activities (which already make DTB’s overworld far more engaging than the majority of RPG overworlds), each task is fundamentally simple and doesn’t become more complex or layer with other elements to create more sophisticated gameplay challenges. So naturally such simple gameplay can only sustain a certain amount of interest over an extended period of time.

Dream World

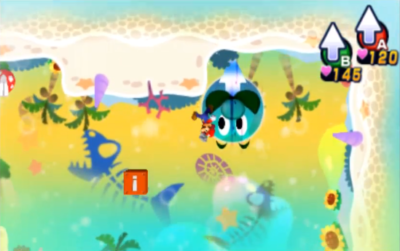

The dream world frames the action from a sidescrolling perspective and most of the challenges incorporate the new Luiginary mechanics. Yet despite these significant changes, these sections still lack meaty gameplay.

AlphaDream designed the dream world sections in accordance with its side-scrolling camera which allows the player to easily judge the height of jumps. So the levels consist of a series of connected rooms with various platforming challenges. Gravity plays an important role in these challenges, but the force is perhaps too strong as the Bros. don’t hang for very long at the apex of the jump. Having the two Bros. jump at the same time further hampers the jumping trajectory. And so overall, these limitations restrict the potential range of actions possible with the jump mechanic. Factor in a lack of acceleration or momentum and navigating the dream world is almost as static as navigating the overworld. The main difference is that the camera enables players to jump over enemies instead of walking around them.

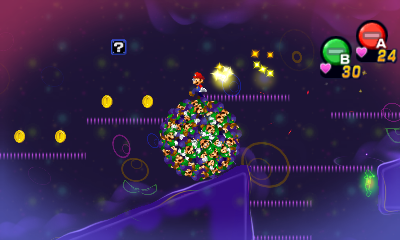

Unlike the mostly static out-of-battle abilities in the overworld (and the rather static jumping in the dream world!), each of the dream world’s Luiginary Works have a dynamic quality or hook. Some examples include:

Luiginary Stache Tree – The elasticity, ability to angle of shots, and having to predict trajectories leading off-screen according to visual memory

Luiginary Ball – The momentum built up by the ball

Luiginary Cylinder – The physical manipulation of the drill via Luigi’s nose on the touch screen and the player-controlled timing challenges which emerge from it.

Luiginary Gravity – This mechanic changes the way the player understands and interacts with the level design, opening up spatial challenges which require lateral thinking.

Luiginary Propeller – Wind acts as a dynamic force which affects movement, jumping, and potential interactions.

To accommodate the broader movement ranges of some of these abilities, AlphaDream housed the Luiginary Works challenges in large rooms. However, the developers failed to strike an appropriate balance between rooms sized for specific Luiginary Works and those sized for the relatively pint-size Mario Bros. Far too many rooms are sized beyond their purpose, leading to an abundance of negative space within the levels.

Aside from the room sizes, the Luiginary Works challenges have a number of their own issues. Although the more dynamic actions make the challenges more engaging than the overworld puzzles, the mechanics are simply overused and become repetitive, especially in the early and middle portions of the game. The challenges also aren’t particularly difficult. It’s easy to just switch off your brain at many points throughout the game. I was hoping that Dreamy Neo Bowser Castle would combine the abilities together to create a super end-game challenge, but only one type of Luiginary Works ability can be used per room. Although this decision keeps the interface clean, it also limits the potential design space.

Despite its sidescroller presentation, the dream world doesn’t differ much from the overworld. The player can jump over enemies as well as navigate around them; however, with strong gravity and few dynamic properties, jumping provides a limited range of movement. The Luiginary Works mechanics are far more dynamic and interesting than the overworld mechanics, but their respective challenges are easy, repetitive, and drawn out due to the oversized environments. For every step of progress, the game takes another step backwards.

Conclusion

In developing Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros., AlphaDream doubled the size of the game content in response to fan feedback from Bowser’s Inside Story. A sizable portion of the increase in content came from the larger overworld and expanded dream world gameplay. Unfortunately, these sequences are rather simplistic and static in comparison to the main combat gameplay. The lengthier adventure only highlights the shortfalls of these low intensity moments of gameplay. As a result, Dream Team Bros. often drags its feet across the extended forty-hour story.

Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros. – Table Design Meets Overworld Design

April 28th, 2018

Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros.‘s hub-based overworld design and Bowser’s Inside Story‘s organic overworld design function much like the circular dining tables of Chinese culture and the rectangular dining tables of Western culture.

Round tables symbolise collectivist ideology where all participants are equal. Each member sits equal distance apart and is therefore able to see everyone else at the table and easily participate in group discussion. With Dream Team Bros.‘s hub-based map design, each area is equal distance apart and requires roughly the same amount of play time to complete. Players can easily navigate between areas through the centre point (engage in the main conversation) or move between adjacent areas (converse with the person next to them). Since everything is orientated around a centre, the design minimises the amount of backtracking (private conversation).

Rectangular tables contain a head and a foot for those individuals of distinction. Similarly, Bowser’s Inside Story‘s worlds of varying shapes and sizes fit within the confines of a rectangular box. The access to different areas of the map is therefore uneven much in the same way that someone on one side of a rectangular table might struggle to speak to someone on the other side. The design favours those who sit in the middle of the table and are able to navigate between conversations on either sides. Meanwhile the corners remain isolated. Usually, if someone wishes to talk to a person outside of clear speaking distance, they’ll move or switch chairs at some point later in the meal. Similarly, as the player progresses through BIS, they’ll discover the underground train network known as Project K which allow them to fast travel across the map.

What I like about games like BIS is how this unevenness in the overworld design characterises the play experience. Dimble Woods and Blubble Lake are frequent junctions, sharing the centre area of the map. You pass through these areas multiple times and they have multiple entry and exit points. Toad Town joins Blubble Lake and Peach’s Castle, while Plack Beach archs around between Dimble Woods and Cavi Cape. Both areas act as a sub-juncture. Bumpsy Plains is a small join between areas. The remaining locales dwell on the outskirts and naturally take longer to reach. To further complicate the relationship between these areas, the Project K railroad links the fringes in a circle. The uneven jigsaw of worlds gives each area a personality pertinent its relative positioning and functional role within the geography. The dynamics of space and mobility play out much like the social dynamics governing where we choose to sit and who we choose to sit next to at a rectangular table.

In terms of its impact on the experience, the design of a table doesn’t differ much from the design of an overworld in a video game. These analogies work because the dynamics of space and mobility are universal.

Mario & Luigi: Bowser’s Inside Story – Traditional RPG Systems meets Functional Design

December 17th, 2016

Bowser’s Inside Story‘s battle system adheres to Nintendo’s clean and functional approach to game design (see earlier articles on narrative and level design). Attacks operate in real time and test a variety of different skills, while the turn-based structure organises the moments of action into clean, discrete chunks. This strong core is surrounded by levelling, equipment, and badge systems which both enhance and weaken the game’s key asset. In this post we explore what happens when functional design meets traditional RPG systems.

Stats and Levelling

BIS retains the levelling system of the earlier games. As the player defeats enemies they gain experience points through which they level up and increase their attack, defence, and other stats. Levelling up is necessary to counter the increasingly stronger enemies the player encounters on their journey. This connection between levelling and enemy strength sustains most RPG battle progression. And yet I don’t believe that it serves the genre—nor BIS—very well.

BIS’s battles hinge on the player’s ability to successfully attack and dodge enemies. We know this because if a player cannot achieve these actions, then they will lose. Assuming the player is levelling up their eyes, mind, and fingers (which they are by virtue of them defeating a stream of unique enemies), then what purpose does having statistically stronger enemies serve other than to artificially inflate the difficulty? More to the point, how does levelling enhance the attacking and dodging functions which are central to BIS’s battle system? The numbers on screen change, but the animations, hit boxes, tells, and mix-ups powering the core functions remain the same.

(I’m a bit worried that my proposition here is somewhat simplistic, but so far I haven’t been able to come up with a counter argument, so we’re going to roll with it for now).

I would be lying, however, if I were to claim that the numbers game doesn’t serve some useful (albeit limited) purposes. Levelling clearly communicates to the player their progress in the form of a digit, even though they have no barometer at which to measure, compare, and ultimately make sense of the number. The player can also use levelling as a means to increase or decrease the challenge as needed by either avoiding or grinding enemies. Unfortunately the leeway afforded by levelling systems can be exploited so as to decrease the challenge to the extent that the game is unable to “squeeze” the player and express meaning through its gameplay challenges.

By removing the levelling system and visible statistics (aside from HP and SP), more emphasis would naturally fall on variation within the battle system (variation between individual challenges = difficulty curve). Between the large range of enemies, different combinations of enemy types, the enemy mix-ups, differences between the Bros and Bowser attacks and dodges, and external elements such as Bitties, there’s more than enough variation to sustain the gameplay. The player would still have access to a variety of existing means of scaling the difficulty, such as buying healing items or finding more beans. Speaking of which, a lack of levelling would increase the significance of beans and encourage the player to partake in this worthwhile side activity.

Equipment

The clothing (equipment) system is similar to levelling, but not quite. Multiple times throughout the adventure the player can spend coins on new clothing items which increase either the Bros.’s or Bowser’s stats. This routine adds another layer of artificial progression and does not support the core of the battle system. Purchasing goods itself also isn’t terribly interesting. Yet like levelling, equipment provides some wiggle room for less proficient players. Assuming enemy stats did not rise as the player reaches new areas (as mentioned earlier), I think it would be best if the clothes stores in the Mushroom Kingdom all closed shop.

Closing down the clothing shops wouldn’t actually have a significant effect as a great deal of clothing items aren’t available in shops. Rather, they’re strewn across the overworld in various nooks and crannies. In this sense, clothes are similar to beans, a reward for being observant and participating in extra tasks on the overworld. So while buying gear only serves to combat the artificial growth of enemies, finding gear makes the overworld portion of the game more engaging.

I would be remiss in not mentioning that a significant number of clothing items do more than simply prop up the stats of the avatars. Some items regenerate health, increase the chance of critical hits, potentially make the enemy dizzy after you jump on it, etc. Again, I can’t really fault this aspect of the equipment system either because such gear adds player-determined variation to the battles and encourages the player to experiment with different strategies and gameplay styles. Below, I have included some of my favourite examples:

Coin Socks

If the wearer takes no damage during a battle, 1.5x coins awarded

Gall Socks

Foes are 50% more attracted to attack the wearer

Challenge Medal

All enemies have HP, DEF, & SPEED increased by 50% and POW increased by 150%, but coins gained from battle increase by 50%

Heroic Patch

Special attack POW +30%, but SP cost doubles

POW Mush Jam

When wearer eats any type of mushroom (healing item), POW +20%

I just couldn’t go past the Softener Gloves:

Due to a coding error, occasionally raises enemy DEF by 25% rather than lowering it.

The examples above are unfortunately the exception and not the rule. The majority of non-stat-increasing clothing items are buffs and therefore aren’t terribly different to stat boosts at all. Where levelling was completely artificial, the equipment system is perhaps half synthetic (the routine of buying better gear and clothing as buffs) and half functional (clothing as collectables, clothing as adding variation and options to battles).

Badges

Badges are the third and final piece in the pie of systems which surround the core battle system. Mario and Luigi each have their own badge halves which connect together. As each character lands “Good”, “Great”, and “Excellent” (well timed) hits, their badge meter increases. Once both meters are maxed, the player can tap the touch screen to activate an effect. Mario’s badge determines the effect and Luigi’s badge determines the degree of effect. Unlike levelling and equipment, badges support the core functions of the game by rewarding the player for attacking and countering enemies. They also allow the player to customise battles so as to support their own playstyle. For example, I set the badges up so that after landing enough well timed attacks, I could heal half of the Bros’s SP. This meant that I had more opportunities to use the special attacks, something which I felt I needed more practice with.

The levelling system and some parts of the equipment system don’t support the core of what makes BIS’s battle systems so unique and engaging, and so they’re more like clutter than the potent force they are in more traditional RPGs. On the other hand, badges and some parts of the equipment system support the core functions of attacking and dodging and also enhance other areas of the game, such as the player’s engagement with the overworld. So depending on the implementation, traditional RPG systems can both complement and clutter a functionally designed core.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99