Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros. – Where Skilful Play Ends

May 4th, 2018

Within games criticism exists a niche subset of “challenge-run” criticism where a player will attempt to beat a game while adhering to a set of self-imposed rules. These rules—such as, not firing a bullet or trying to beat the game on one life—act as a prism through which the player can then critique the game. Personally, I’m not a fan of this form of criticism, but I have started using some of the techniques to help me become a better player and hence a more insightful writer. For example, last year I beat The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword with only three hearts in order to better understand the motion-based combat.

Given my dislike of levelling and equipment systems in the Mario and Luigi games, I played Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros. underleveled and paid little attention to the equipment system. As with Bowser’s Inside Story, I used the badge system as a means to top up my SP so that I had more opportunities to master the Bros. and Luiginary Attacks. These decisions, I believe, allowed me to play a more skilful game and better understand the core actions of the combat system.

“Challenge runs” usually bring a particular aspect of a game into focus, and for Dream Team Bros. my more skill-based approach left me unprepared to tackle the game’s surprising number of difficulty spikes. Friend and regular commenter on the Daniel Primed blog, CM30 covered the worst offenders in his piece Opinion; Mario & Luigi Dream Team’s Toughest Bosses, so I’ll let his words do the legwork here. Given AlphaDream’s attempt to make the series more approachable to a wider audience, this issue stands out as a major oversight. Fortunately, I could overcome most of the difficulty spikes thanks to gold ol’ fashion attacking and dodging—and a long view towards winning the war of attrition. However, my earnest attempts were no match for Dream Team Bros.‘s final boss Dreamy Bowser.

The confrontation is simply rigged. Initially at least, the gaudy-coloured tyrant plays out like most other boss battles. However, after the first few turns Bowser then withdraws into the background to chow down on a magically spawned pile of meat, curing around 500 HP across him body and arms. Each turn another pile of meat drops out of thin air and Bowser’s mid-battle snack continues while the player is left strong-arm their way through an army of technicoloured goons. Even if the player uses a taunt ball on their next turn to lure Bowser back into the foreground (an already somewhat nuanced move), Bowser will have already recovered a significant amount of damage. And so the war of attrition rages.

The biggest problem with this battle is the difficulty of Bowser’s attacks and the protracted learning process it takes to learn the tells. Each individual attack is actually a sequence of smaller attacks which run over a continuous period of time, and Bowser will usually attack more than once per turn. Furthermore, since one mistake can throw off the timing needed to stay in sync with the sequence, individual hits can quickly snowball. When this happens, the player needs to heal, in turn conceding an opportunity for Bowser to heal as well. If one of the Bros. is knocked out, then the player must forfeit the entire turn in order to reconsolidate. So the player must avoid most attacks or struggle against the slippery slope.

From my experience, the war of attrition rages for about 10 minutes before Bowser’s HP drops to where he’ll start using his strongest attacks. However, should the player fail to adequately respond to Bowser’s new moves (which they likely will as they need time to learn and encode the new attacks into memory), then they’ll have to spend another 10 minutes in the trenches. Hence, the process of mastering Bowser’s later attacks is highly protracted.

My “challenge run” had taught me that playing Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros. as a purely skill-based game with little investment in the levelling and equipment systems has its limits. In this case, Dreamy Bowser is the point where player skill no longer translates into success in the combat system.

Postscript

After struggling against Dreamy Bowser for several hours and ready to put Dream Team Bros. on the shelf, I was airing my grievances with CM30 when he gave me a tip. He suggested that I equip the Miracle and Gold badges, grind up some badge meter, and use their power to freeze Bowser for a few turns. This way I could squeeze in one more attack per turn and finish him off before he entered into his meat-eating recovery state. And it worked! Within 5 minutes I had Bowser beat (CM30 did it in three!). So maybe skill wins after all!

Additional Readings

Six Challenge Runs Everyone Should Try – USGamer

Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros. – The Limitations of RPG Overworlds

May 1st, 2018

“Compared to previous games in the series, this one has a lot of volume. A lot of people said they wanted more to play in the third game, so I definitely wanted to increase the volume a lot for the next one.”

Akira Otani, game producer of Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros.

Akira Otani and AlphaDream’s aspiration to increase the game volume of Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros. is perhaps best summarised by the data below taken from How Long to Beat, a play time aggregate website based on user submissions.

Superstar Saga – Main Story: 18.5 hours Completionist: 27.5 hours

Partners in Time – Main Story: 18 hours Completionist: 37 hours

Bowser’s Inside Story – Main Story: 22.5 hours Completionist: 35.5 hours

Dream Team Bros – Main Story: 40.5 hours Completionist: 60 hours

NB: The play times on the site are constantly changing due to new submissions, so these times were captured at the time of writing.

As you can see, Dream Team Bros. is as large as the previous two games combined. The question is, where does the extra 20 hours of gameplay come from? Unfortunately, answering that question would require a massive amount of data on how long players spend in particular sections of the game, which isn’t so feasible. Based on my own experience with the Mario and Luigi series, I would argue that the following factors contributed significantly to Dream Team Bros.‘s extended play time:

- the new Luiginary Works mechanics and their respective level challenges which bulk up the sidescrolling gameplay

- the larger map sizes which increase the time spent in the overworld

- the expanded swarms of peon enemies which extend the duration of battles

The influx of peon enemies create more spatial and strategic gameplay (which is covered further in Adventures in Games Analysis). However, they can protract the length of battles if the player doesn’t pay attention to the specific group AI patterns and exploits these weaknesses. Then again, the same can be said of the core action-reaction interactions as well.

For the purpose of this article, I’m more concerned with the increased amount of time spent outside of combat as these sections—like in most RPGS—are the less interesting parts of the game. Whilst games should include gameplay of varying levels of intensity (with combat, in this case, being the most intensive), Dream Team Bros.‘s forty-hour play length only makes the minimal gameplay outside of combat more apparent. This is particularly the case for the dream world challenges, which constitute a significantly larger portion of the gameplay mix than in Bowser’s Inside Story. But why exactly are these areas of the game so lacking in the first place?

Overworld

The isometric overworld gameplay benefits from the basic dynamics of space and the limitations of the camera perspective. The camera only captures the area directly around the Bros. and so the player needs to move around each environment to trace the outline of each room and mark points of interest in their short-term memory. Once the player has enough knowledge of their surroundings, they can make an informed decision about how to engage with the particular challenges of the room. This simple form of cartography provides the most basic form of engagement on the overworld.

As the player moves around and checks items into their short-term memory, they’ll probably put enemies at the top of their mental checklist. Similar to the Zelda games, enemies populate the Dream Team Bros.‘s overworld and persuade the player to move in particular ways. However, the overworld is not tightly tuned around these interactions. When contact with an enemy instantly warps the player into a battle which can last several minutes at a time, the developers don’t have many options for increasing the richness of these interactions without skewing the game disproportionally towards combat. So in balancing the consequences of touching an enemy on the overworld, the developers give the player enough space to slip past their foes without too much trouble.

Further to the points above, the camera and jump mechanics simply cannot facilitate the act of subtly avoiding enemies in space. Even with the stereoscopic 3D screen, the isometric camera perspective inherently has difficulty communicating the distance between bodies in space. Luigi, as a trailing partner, also collapses the space around the player.

Tying simple cartography and avoiding enemies together, puzzles pave the player’s path to progression. AlphaDream designed the majority of puzzles around the Bros. out-of-battle techniques, such as jump, hammer, and ball hop. Unfortunately, even though the player can usually use these abilities on a wide range of game elements, the mechanics lack the dynamic qualities and nuances necessary to facilitate a variety of engaging puzzles. With so little complexity to work with, the Bros.’s abilities usually function as little more than keys to locks and most puzzles revolve around the player using their various keys to activate switches in a particular order so as to access a new area.

Being a Mario and Luigi tradition, AlphaDream baked in various collectables into Dream Team Bros.‘s overworld, namely beans. In Bowser’s Inside Story the player, as Bowser, explores the overworld map and comes across bean holes which they cannot uproot. Since these bean holes are hidden in plain sight, players have to store their locations in their short-term memory for several hours until the Bros can make it out to the overworld and uproot them. When the Bros. do escape, the player can explore the overworld from whichever direction they wish, and so the order by which the player recalls the locations of the beans is very organic and player-driven.

In DTB, beans add an observation element to exploration. However, the game lacks the dynamic memory suspension twist of BIS as the player can collect the majority of beans on their first pass through an area.

Although the overworld contains a small set of diverse activities (which already make DTB’s overworld far more engaging than the majority of RPG overworlds), each task is fundamentally simple and doesn’t become more complex or layer with other elements to create more sophisticated gameplay challenges. So naturally such simple gameplay can only sustain a certain amount of interest over an extended period of time.

Dream World

The dream world frames the action from a sidescrolling perspective and most of the challenges incorporate the new Luiginary mechanics. Yet despite these significant changes, these sections still lack meaty gameplay.

AlphaDream designed the dream world sections in accordance with its side-scrolling camera which allows the player to easily judge the height of jumps. So the levels consist of a series of connected rooms with various platforming challenges. Gravity plays an important role in these challenges, but the force is perhaps too strong as the Bros. don’t hang for very long at the apex of the jump. Having the two Bros. jump at the same time further hampers the jumping trajectory. And so overall, these limitations restrict the potential range of actions possible with the jump mechanic. Factor in a lack of acceleration or momentum and navigating the dream world is almost as static as navigating the overworld. The main difference is that the camera enables players to jump over enemies instead of walking around them.

Unlike the mostly static out-of-battle abilities in the overworld (and the rather static jumping in the dream world!), each of the dream world’s Luiginary Works have a dynamic quality or hook. Some examples include:

Luiginary Stache Tree – The elasticity, ability to angle of shots, and having to predict trajectories leading off-screen according to visual memory

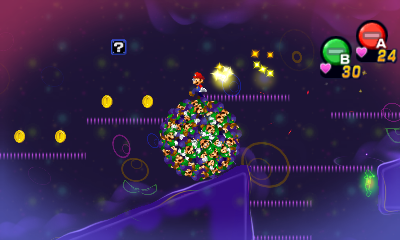

Luiginary Ball – The momentum built up by the ball

Luiginary Cylinder – The physical manipulation of the drill via Luigi’s nose on the touch screen and the player-controlled timing challenges which emerge from it.

Luiginary Gravity – This mechanic changes the way the player understands and interacts with the level design, opening up spatial challenges which require lateral thinking.

Luiginary Propeller – Wind acts as a dynamic force which affects movement, jumping, and potential interactions.

To accommodate the broader movement ranges of some of these abilities, AlphaDream housed the Luiginary Works challenges in large rooms. However, the developers failed to strike an appropriate balance between rooms sized for specific Luiginary Works and those sized for the relatively pint-size Mario Bros. Far too many rooms are sized beyond their purpose, leading to an abundance of negative space within the levels.

Aside from the room sizes, the Luiginary Works challenges have a number of their own issues. Although the more dynamic actions make the challenges more engaging than the overworld puzzles, the mechanics are simply overused and become repetitive, especially in the early and middle portions of the game. The challenges also aren’t particularly difficult. It’s easy to just switch off your brain at many points throughout the game. I was hoping that Dreamy Neo Bowser Castle would combine the abilities together to create a super end-game challenge, but only one type of Luiginary Works ability can be used per room. Although this decision keeps the interface clean, it also limits the potential design space.

Despite its sidescroller presentation, the dream world doesn’t differ much from the overworld. The player can jump over enemies as well as navigate around them; however, with strong gravity and few dynamic properties, jumping provides a limited range of movement. The Luiginary Works mechanics are far more dynamic and interesting than the overworld mechanics, but their respective challenges are easy, repetitive, and drawn out due to the oversized environments. For every step of progress, the game takes another step backwards.

Conclusion

In developing Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros., AlphaDream doubled the size of the game content in response to fan feedback from Bowser’s Inside Story. A sizable portion of the increase in content came from the larger overworld and expanded dream world gameplay. Unfortunately, these sequences are rather simplistic and static in comparison to the main combat gameplay. The lengthier adventure only highlights the shortfalls of these low intensity moments of gameplay. As a result, Dream Team Bros. often drags its feet across the extended forty-hour story.

Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros. – Table Design Meets Overworld Design

April 28th, 2018

Mario and Luigi: Dream Team Bros.‘s hub-based overworld design and Bowser’s Inside Story‘s organic overworld design function much like the circular dining tables of Chinese culture and the rectangular dining tables of Western culture.

Round tables symbolise collectivist ideology where all participants are equal. Each member sits equal distance apart and is therefore able to see everyone else at the table and easily participate in group discussion. With Dream Team Bros.‘s hub-based map design, each area is equal distance apart and requires roughly the same amount of play time to complete. Players can easily navigate between areas through the centre point (engage in the main conversation) or move between adjacent areas (converse with the person next to them). Since everything is orientated around a centre, the design minimises the amount of backtracking (private conversation).

Rectangular tables contain a head and a foot for those individuals of distinction. Similarly, Bowser’s Inside Story‘s worlds of varying shapes and sizes fit within the confines of a rectangular box. The access to different areas of the map is therefore uneven much in the same way that someone on one side of a rectangular table might struggle to speak to someone on the other side. The design favours those who sit in the middle of the table and are able to navigate between conversations on either sides. Meanwhile the corners remain isolated. Usually, if someone wishes to talk to a person outside of clear speaking distance, they’ll move or switch chairs at some point later in the meal. Similarly, as the player progresses through BIS, they’ll discover the underground train network known as Project K which allow them to fast travel across the map.

What I like about games like BIS is how this unevenness in the overworld design characterises the play experience. Dimble Woods and Blubble Lake are frequent junctions, sharing the centre area of the map. You pass through these areas multiple times and they have multiple entry and exit points. Toad Town joins Blubble Lake and Peach’s Castle, while Plack Beach archs around between Dimble Woods and Cavi Cape. Both areas act as a sub-juncture. Bumpsy Plains is a small join between areas. The remaining locales dwell on the outskirts and naturally take longer to reach. To further complicate the relationship between these areas, the Project K railroad links the fringes in a circle. The uneven jigsaw of worlds gives each area a personality pertinent its relative positioning and functional role within the geography. The dynamics of space and mobility play out much like the social dynamics governing where we choose to sit and who we choose to sit next to at a rectangular table.

In terms of its impact on the experience, the design of a table doesn’t differ much from the design of an overworld in a video game. These analogies work because the dynamics of space and mobility are universal.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99