An Overview of A Theory of Fun (Raph Koster)

October 30th, 2009

I’m not sure when exactly, but sometime in the next 6 months I will don the felt hat and graduate from university. Actually, I probably won’t be in Australia for the ceremony, in fact I’m planning on having a faux graduation ceremony involving a lot of sea food and karaoke, but anyways, you get the point. It’s great news by all means, except that this year I’ve rediscovered the usefulness of the student library and losing my privileges there will be a bit of a bummer.

You see, I live some way from my campus and as I commute via public transport, I’m left with a plentiful amount of time in transit. I’m not the kind of person to take the DS or PSP out with me in public though, since the noise, glaring sun and commotion de-immersifies the experience, so long as I don’t bump into a friend along the way I prefer to read.

This year I’m not flooded by course material to read over, so I’ve turned my attention to the library and have been enjoying the works of Erving Goffman, Xiaolu Guo, Henry Jenkins and a series of readings on Chinese communication theory and culture. I’ve actually found myself on a bit of a roll and have moved on to a handful of books on game design, before I then start on material written by former left-wing British politician Tony Benn, shortly followed by a slew of graphic novels. I’m kinda trying to squeeze it all into my final year media binge before I return to China for work.

Anyways, along with the rest of the media I’ve consumed this year, I hope to reinforce what I’ve learnt by sharing my summative thoughts here on my blog. Not all of it will go here, some of it—irrelevant to games—I shall post elsewhere, but for now let’s talk about A Theory of Fun for Game Design by Raph Koster.

Theory of Fun is about more than fun, it’s the layman’s book for understanding video games—and considering where our understanding of this medium currently is at the moment, Theory of Fun is no less essential reading. I can’t recommend this book enough. I want to buy a copy for my brother and then convince my whole family to read it as it simply makes sense of what is often an over complicated topic. Raph asks the fundamental questions and answers them in a personal, insightful and humourous way. Every second page features a hand drawn comic further explicating his logic, usually in a humourous and highly effective manner.

That’s the mini-review, let’s unpack a couple of the ideas I personally found of interest. Keep in mind though that for some of these headings I’m adding my own additional thoughts or forming my own conclusion from what was said, separate from the book.

Games are Perhaps More Real than Reality

Cognitive processes ensure that our brain packages much of the world around us thereby making it easy to interface with. It ensures that many of our actions are routinely done without much use of brain muscles at all. Think of how you got dressed this morning, what steps did you take? Did you put on a shirt first and then your underwear? Don’t remember? Thought not.

This process, according to Raph is called “chunking” and with it it’s easy to argue that much like the film The Matrix, the reality we perceive may in fact not be reality at all, but instead a reality in which our brain has trimmed down to only what is serviceable. Video games then, represent a different kind of reality. Of course, when we play games our brain still chunks whatever is happening on screen, but more to the point: The reality represented in games are realities which are delivered pre-chunked by the game designer. That is, all games are designed to be interfaced with, and the way interfacing is conveyed to the player is a design choice made by the game designer. Some obvious examples of chunking might be: the distribution of platforms and climbable objects in Prince of Persia, the greying of the screen nearing death in Killzone 2, the distribution of light in Thief or the way terrain guides the player in Half-life. These elements are representative of their respective functions.

Games are Education, Game Designers are Teachers

In order to survive and grow healthily, the brain needs to crunch patterns. Patterns are infinitely available and can be accessed through almost any means, such as communication with people, photography, music, observing nature, writing, falling in love. In essence, the brain craves education, we actually enjoy learning and all of the above examples involve some form of education.

Video games have become such a successful medium because they are good educators. Video games are all about acquainting a player with a set of continually elaborate rules and testing the player on their application of these rules in a situated context. As I’ll discuss to greater length later on when I talk about James Gee’s Good Video Games and Good Learning, games are fundamentally education driven by nature and therefore very powerful. In this regard, game designers are teachers crafting the education process.

Players are Destined to Make Games Boring

Because players play games to learn, we consequently play games to reach the point in which we’ve learnt everything that the game can offer us. That is, we play games in order to make them boring.

Grok

A term in which someone understands something to the point that they become one with it and therefore fall in love with it. When we play a good game we grok the system of rules and mechanics of the game.

How Boredom Settles In

The player may grok the game too quickly, therefore finding the game “too easy”.

The player may not see value in understanding the rule system and complexity (see how Super Paper Mario avoid this drama)

The player might fail to see any patterns, they just see noise “It’s too hard”

Pacing may be too slow, the game may seem too easy too quickly

The game may do the opposite as above: become too fast too quick

The player beats the game

Players are Always Interested in the Win

Raph argues that people are naturally lazy (and don’t wish to learn) therefore they exploit the game’s weaknesses and blind spots and cheat if possible. He says that players ought to avoid doing this as it demeans the point of playing which is to teach and then test the player. In this regard, lazy players are bad students.

This is also why Super Metroid is such a fantastic title, it guides the player into the mentality of exploiting as much as they possibly can out of the environment, yet always stays one step in front of them. Super Metroid effectively straddles the player for all they’re worth. This is what makes Super Metroid akin to a good fitness instructor: motivating yet always pushing.

Game Design and Dressing

There are two core parts to a game: the design and the dressing. The game design is obviously the fundamental components of a game, including the core and peripheral mechanics and the way everything is designed and put together. The dressing is the context that the game places itself in as represented by the game’s presentation. Differentiating the two, when a player plays the game they primarily see the game design, but when an onlooker watches the game they often just see the context, particularly if the onlooker is unfamiliar with games in general.

Raph later explores this dynamic with the GTA franchise. He says that in GTA, players see picking up a hooker, participating in a drive-by shooting or beating up civilians as a way to make progress (the game design), yet people who don’t play the game (ie. parents) see the player committing acts of virtual terrorism.

When minority groups and the media protest against video games, they protest against the wrapping and not the game design. Game design and mechanics are really just an abstract system of rules, context is what frames a video game as being socially responsible or destructive.

Even though many people say that graphics and presentation don’t matter, they actually do because after all we’re visual creatures which receive pleasure by the visual and aural landscapes that video games so fruitfully provide. In saying this, the game design is always the crux of the experience.

Lack of Evolution from the Roots of Design

Nearing the end of the book Raph discusses how game design has become increasingly more narrow, expanding primarily from the branches and not from the roots. He cites shoot ’em ups as an example, saying that they’ve become completely irrelevant in today’s gaming society because the genre never evolved much beyond their original design.

Geometry Wars is a minor exception to his assertion, as I’ve discussed here before, through its use of technological capabilities the game managed to reignite interest in the genre by shifting the general design of arena based shoot ’em ups. It’s not a fundamental divergence though, so in perspective the shift is only slight.

The Difference Between Games and Stories

I’m just going to quote directly from the book here.

Games are not stories. It is interesting to make the comparison, though:

Games tend to be experimental teaching. Stories teach vicariously.

Games are good at objectification. Stories are good at empathy.

Games tend to quantize, reduce, and classify. Stories tend to blur, deepen, and make subtle distinctions.

Games are external—they are about people’s actions. Stories (good ones, anyways) are internal—they are people’s emotions and thoughts. [Pg 88]

Rethinking Play Habits

In the same regard to his belief that players always want to cheat, Raph believes that players should not replay games as there is often little educational benefit in playing a game twice. I’m sure many would argue against his point here, myself included.

Self-serving Medium

I think most of us would agree with this one: video games have become too complicated and too arcane in their obedience to the core market. Players who enjoy games enter game development with the pursuit of making the games in which they enjoy, therefore the games industry is largely compiled of developers serving the interest of a small group of core players. This system doesn’t invite new players into the fold nor does it allow the medium to further expand.

The Next Step

According to Raph, for games to become designers need to design games which represent something of social importance. He says that games should begin to explore the human condition by representing and/or metaphoring game design as something of actual importance. Well said.

Additional Readings

A Modder’s Perspective: ‘A Theory of Fun for Game Design’ by Raph Koster

Metroid Prime 3: Quarterly Diaries #9

October 28th, 2009

Areas Covered: Landing Site Bravo

Discussion Points: Visual design of the Pirate Homeworld, space pirate lore scans, looping environments in the Metroid series, the use of acid rain, x-ray visor

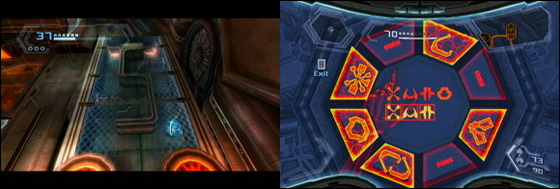

Landing Site Bravo (Pirate Homeworld)

Considering the Space Pirates’ feverish hate for federation bounty hunters named Samus Aran, it’s bewildering that they’d simply allow her to steer her ship right on through to their command and research centres without any kind of safeguard or inspection. In any case, we’re here now, let’s make the most of it!

Visually, the Pirate Homeworld shares the same dark, ominous tone of GFS Valhalla, the key exception being that the landscape is draped in a confronting, bloodshot red fog. Perhaps it’s over saturated, but, as with the Dark World in Metroid Prime 2, it seems uncharacteristically dark by intentionally drawing together design elements which clash and overpower one another. It’s ugly enough to instill repulsion without the game appearing artistically flawed. The red is very overpowering, working with the enclosed architecture to almost suffocate the player.

The pirate lore scans in this area, as has been the case with the other pirate entries from the previous two games, are absolutely fascinating to read as they throw light on the fringe operations of the rogue group in a way characterized by the pirates themselves. The lore scans here also serve to fill in the blanks on the pirate’s exploits since Metroid Prime 2, including their recent allegiance with Dark Samus. The scans, written from the perspective of the pirates, depict Dark Samus as something of a messiah, who through uniting the race with phazon, has finally given the pirates strength in the ongoing battle against the Galactic Federation. I know the space pirates are an over-zealous bunch—the previous games have said this much—but they seem of either complete desperation or completely warped by the involvement of Dark Samus. Maybe it’s got something to do with her influence over the processing of phazon. I’m curious to see how this whole saga ends.

The Metroid games always operate in a hub environment with an overworld connecting to a series of smaller areas. Each of these individual areas are designed so that the player ends up looping around, returning to their point of entry (or similar) in the overworld. This looping dynamic is either designed in a linear fashion, wherein the environment itself loops around or by relying on backtracking which—on the reverse path—rejigs the route so that the latest weapon upgrades can be utilized, thereby making the retread enjoyable. That’s not to say that the former doesn’t also tutor the newly-acquired weapon upgrades, it does, but it’s just progressional with the linear path, rather than relying on a rejigged environment etc. We’ve discussed both design techniques and their application numerous times before in this series, I just hadn’t really put it forward so discreetly yet. So in saying this, the Landing Site Bravo area relies on a linear route which loops through at the gate of the first floor elevator. It also ties in nicely with the map station which is concealed from players when they first make entry into the environment.

When you arrive to the Command Courtyard there’s a cutscene which shows a pirate entering the main section of the facility, the cutscene also highlights two upgrades which you’ll acquire in this area, being the hazard shield (the glow around his body) and the Grapple Voltage (the gate’s force field).

As a choice of environmental design, I’d probably criticize the acid rain plaguing the homeworld as being a little too cliché of dystopic environments, but functionally it’s quite clever. The acid rain throughout the Pirate Homeworld works as a tool to segregate the environment based on whether or not you have the hazard suit upgrade. The acid rain also has a multitude of other functions, here’s a list of what I came up with:

1 ) Heavy rain is a trope of dystopic environments, so it feels well suited to characterize the epicentre of the pirate’s operations

2 ) The rain doesn’t feel as though it restricts access to other areas of the homeworld, even though that’s its ultimate function. When the player walks out into the rain their suit receives damage, but they are still, seemingly, free to explore these areas despite the fact that the rations of energy tanks given at this point don’t allow you to make any real leeway

3 ) It divides the environment into (safe) interior and (hazardous) exterior components where Samus initially can only explore in sheltered areas…

4 ) …by which case Retro use the initial sequence as an infiltration sequence where the pirates are out in the open and Samus is snooping around behind glass

5 )They also use the divide as a tool for seamless narrative, so while Samus is infiltrating from behind the scenes, she can witness the stage in which the pirates are scheming whatever it is they’re scheming

6 ) By using the rain to facilitate the infiltration sequence, it legitimizes the little combat at the beginning of this area and then afterwards, as Samus obtains upgrades and further mines the complex, it legitimizes the increase in action and thereby difficulty. The presentation is one of common sense.

7 ) The rain quite obviously necessitates the usefulness of the hazard shield upgrade

8 ) If you look up at the drain it splashes black droplets, that’s neat!

After some snooping about Samus, for the second time in the series, discovers the X-ray visor. I must say, the perspective certainly looks a lot prettier than in the original Metroid Prime. I will admit that seeing the bones in her arms is a little creepy. It’s initial application on the codified key pad didn’t really leave me impressed. However, after some time with the visor, I’ve come to realize that overall the key pad mechanic is just a small addition to the application set which the visor can be used for, so it just seems a little underwhelming from the onset for returning players. Furthermore, they mix up the application a little later in the game.

At the end of the stage the player receives a distress call from a marine stationed in the next area, the pirate’s research facility. Time to investigate!

Additional Readings

Design Differences: Metroid Prime 1 and Prime 3

Metroid Prime 3: Quarterly Diaries #8

October 26th, 2009

Areas Covered: Sky Town Spire, Elysia Seed

Discussion Points: Bombing of the Elysia Seed, Helios boss battle

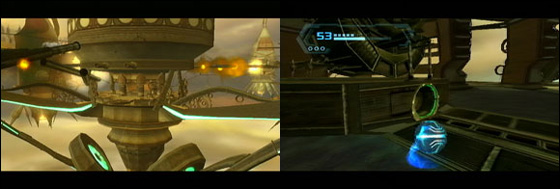

Sky Town Spire

With all of the pieces in place the formal precedings can begin. I never actually clicked previously to what was about to happen here, so when the Aurora Unit explained it to me in plain English, I must confess, I thought it was little convoluted. Let me explain what happens and you can decide for yourself: basically, with all the components assembled the bomb is now primed for launch. Using her ship as a hoist Samus drops the assembled bomb onto the centre-most point of Sky Town. The Aurora Unit then moves Sky Town (yes, the entire network of islands) closer towards the seed and disconnects the centre from the rest of the structure allowing it to free-fall towards the seed. The goal is for the structure to hit shield so that the bomb can explode and power down the force field thereby granting Samus access to the seed. Samus must stay on the structure as it’s falling to prevent any incoming space pirates from diverting the course. Once the bomb is in close proximity Samus can evacuate in an escape pod. The structure hits the shield and the bomb explodes.

This highly scripted premise—which in terms of playable bits consists of defending this free-falling structure armed with explosives only to narrowly escape—seems like something decidedly ripped from an action movie—therefore to a certain extent feels un-Metroid-like. Furthermore it’s questionable whether this set piece was worth the hassle of setting up. Both of these are fair points of criticism and, as with the initial encounter with Ridley, the action feels contrived and forced. That isn’t to take away from the experience, it works quite well and it’s nice to see new ideas applied to the Metroid formula, but it also feels like the creative spark is starting to wear thin.

The crux of this sequence is a tough shootout followed by a tense escape. The shootout is probably the trickiest so far as several ships surround the circular playing field at the one time and pirates are dispatched from them at every side. The danger comes in thick and fast which’ll have you reliant on hyper mode. Once you’ve dispatched enough pirates, you’re clear to activate your escape pod but—OH NO!—the pod is faulty. A small morphball hatch opens for you to frantically head downstairs to mend the device with a series of plasma welding mini games as a timer begins countdown. The setback is predictable but works well, you can see what I mean what I say it’s contrived though.

One final point I wish to make is that this sequence actually made me wishing that the Wii was a little more technically able, simply because the illusion of falling would have been much more effective with something more attractive an ugly brown haze. In fact, the actual illusion wasn’t too convincing and could have benefited from the structure bumping around a little. Also, what’s with the gravity? How is Samus not ripped to the top of the ceiling as soon as the structure begins to free-fall?

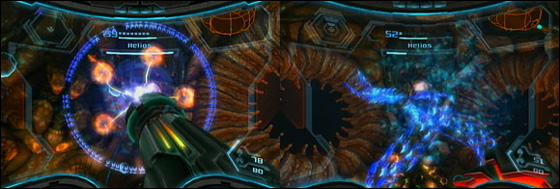

Elysia Seed

In the Elysia seed you take on Helios, a creature made of flying bats which can shift into two shapes: A ball which haphazardly rolls around the arena or a Gunstar-Heroes-esque humanoid who chases you in circles.After blasting off the outer layer of bats, the creature will float in air with 5 red dots revealing themselves around its outer centre at which point you can attack Helios with your seeker missiles to reduce him to his next form. Once you’ve done this you can start dishing our proper damage and eventually whittle him down to nothing.

The battle comprises of a tonn of blasting, stopgapped by a brief moment for the mandatory use of the latest weapon upgrade and then some more blasting. It’s in this regard that the battle feels rather unfulfilling, the meat of it isn’t entirely engaging. Well, that’s partly a lie. Helios has some clever movement patterns mixing up the confrontation so that it doesn’t feel like spam from the blaster. Afterwards you’re rewarded with the hyper missiles and hence we see a trend emerging.

Additional Reading

An Explanation For Metroid Prime 3’s Pointless “Hyper Mode” – Siliconera

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99