Wario Land 4 – Design Discourses

August 12th, 2010

Games with good game design are those where all components of the game are grounded to a core philosophy or set of philosophies. The world of Mario is tied to jumping, the world of Metroid is tied to exploration, and in the case of the Wario Land series, Wario Land is tied to Wario’s wacky persona. Underpinning the philosophy of form meets function, Wario’s outwardly fat, greedy and cartoonishly sinister appearance are a reflection of his abilities and the interactions made possible within the game world. Let’s use Wario Land 4 as an example to briefly observe the way Wario’s character reflected by his interaction and abilities.

Weight

Wario’s array of moves are all tied to utilising his best asset, his visibly bulging weight and super strength. Just like the stylised visual appearance of the character, Wario’s strength and weight are exaggerated through his interaction. No ordinary obese man could crush through rock, create minor earthquakes, flatten small minibeasts or turn into a menacing snowball by building momentum off diagonal slopes, however, Wario can.

Aggression and Greed

Wario’s is presented as an aggressive character. In the game the player is persuaded to be aggressive, meeting the Wario persona, through the rewards of coinage which liberally flows from downed foes. The more aggression you show, such as by throwing one enemy at another, the more the player is rewarded. Unlike in prior Wario games, Wario has a health bar this time, so coins are no longer a currency for life. That is, they are no longer handicapped but instead free-flowing. As we can see, on element of Wario’s behaviour (aggression) acts as a means to highlight another (greed).

Self-deprecation

The folded levels of Wario Land 4 that require the player to reach an endpoint and then, pressed by a time limit, run back to the start of the level make fun of the stout fella’s inability to make haste under pressure. This, I’d argue, works to justify the cartoonish nature of the game through self-deprecation. Perhaps a more obvious example is the way Wario shape-shifts into various different forms. Each one seemingly poking fun of Wario as he is stung by a bee, turned into a zombie, set on fire or flattened into a pancake. Every transformation is met with an “oh no!” cry as though Wario wishes to avoid the humiliation.

Conclusion

As we can see, the way Wario can interact, and the way the player is taught to behave are all representations of Wario’s anti-hero persona. These interactive elements don’t just support the visual image of Wario, but are in fact pivotal in defining his character. It’s no wonder then that players of Wario Land 4 and the other Wario games, have such a vivid understanding of the character himself.

God of War II – A Review

August 12th, 2010

Three months ago, and with grand foresight, I vowed to consume as much media (games, movies, comics, books) as I possibly could before I’d leave almost all of it behind as I go to live abroad in China. Some of this media I managed to write about before I left, some of it I’ve subsequently caught up on over the past three months, and then there’s all that note-taking sitting in OpenOffice documents in my writing folder. God of War II belongs to the latter.

God of War II is a direct narrative and gameplay continuation of God of War, which means that, similarly to the Half-life episodes, God of War II streamlines the culmination of mechanics built up by the conclusion of God of War and re-uses them as a base for the beginning of God of War II. By virtue of being welcoming to new players though, Kratos is robbed of these abilities by his father-cum-uber-nemesis Zeus at the game’s onset, acting as a narrative justification to re-teach the ropes and warm players into the experience*.

For continuing players this amounts to a heap redux which God of War II‘s largely peripheral additions to the combat system fail to quell. (Newer players will similarly find the combat stretches beyond its means, but perhaps not as immediately as returning players). A smattering of aggressive new moves mapped to the L1 button when used in conjunction with the face buttons, a spiffied up Rage of the Titans (rage mode) and some new spells do fend off the familiar, but fail to sustain player interest through what is a significantly extended play experience.

That’s not to discount the peripheral additions though, since, as irrelevant as they are to the most established part of the experience (the combat), they do in fact play a part in pushing the game forward. Kratos has a couple of new weapons at his disposal, including a hammer, sword and bow. Aside from the arrow which can be rapidly shot between intermissions of slashing to maintain combos, none of these diversions are given enough spotlight to deliver attention away from the effectiveness of the Blades of Chaos. Smart players will realise that the best way to play God of War II is to ignore these distractions and rely on the tried and trusted attack patterns from God of War while adding a bit of oomph, now and then, with the new L1 attacks or the spells.

It’s a shame that there isn’t enough added variance to the combat as God of War II is an excellent example of good organisation of gameplay elements. God of War II shifts from combat, to puzzling, to platforming, to narrative, to boss battle with an exacting sense of understanding of how much can be bitten off of each of these systems. Furthermore, new mechanics, landscapes and enemy types are interspersed at the most suitable points in the game. You are always presented with something new and interesting just as your enthusiasm for your current occupation begins to wane. Sony Santa Monica clearly nailed this element with a hefty amount player testing, which is why it’s disappointing then that the depleted combat systems works only to subvert the games otherwise great pacing.

It would be remiss of me to forget God of War II‘s stronger emphasis on puzzles, platforming and set pieces, all of which have been well supported by the new time freezing, flying (Icarus’ wings), chain swinging and Medusa’s head mechanics. The set pieces, particularly the flying sequences, are always exciting and well connected to the context of the game (for example, obtaining Icarus’ wings). The boss battles are equally impressive in the way they draw on more elaborate forms of tactics and spatial awareness which isn’t encountered in the moment-to-moment combat.

But ultimately, none of this can save Kratos from that niggling itch that the combat is not fresh and exciting enough to sustain the experience. The end result, which is overbearingly evident by the end of the game, are the large slumps of uninteresting gameplay which undermine the entire production. By failing to directly address the heart of the experience (the combat) in a meaningful way, I don’t think that God of War II is deserving of its title as the “magnum opus” of the PS2. In saying that though, the combat still holds a level of succulence which cannot be denied and despite the lack of revision, God of War II is still a premier action game, particularly in light of the excellent pacing of the experience.

*This last point is surprising given that God of War III simply dumps immediate tutorial on the player.

Super Metroid – The Tenets of a Metroid Game

August 9th, 2010

The Tenets of a Metroid Game

Although Metroid can be categorized as a platforming shooter within a space-themed context, the franchise isn’t so much about the shooting or the jumping at all. Rather, Metroid is all about that misplaced bit of space rock. You know, the one with a little bit of extra fungus. The one that, after met with a morph ball bomb, will string you down a tiny alley to a small chamber containing the next power-up. Progression in Metroid hinges on the abilities granted by various power-ups which are connected to a string of environmental puzzles. It’s in the player’s ability to realize these puzzles through acute observation and then use their ability set to act upon their observations that Metroid reveals its true colors as a game of deep observation and multi-faceted problem solving. Metroid has always relished in being more than what it presents itself as, and series fans appreciate the franchise for valuing the deep implicit over the loud and overt. There’s a maturity in the series which has gone untarnished even as the franchise has evolved from two to three dimensions.

Metroid is also an innovator, but rarely proclaims its achievements on the back of the box. The Metroid games have not just defined but also realized a style of video game narrative that intertwines story with landscape. Oftentimes in a Metroid game, you’ll find yourself entering a world where events have long passed, and as the player you piece together story through the visual, audio and interactive pieces of the landscape (in the Metroid Prime sub-series text is also included). Through it’s environment Metroid builds a civilization and tasks the player as a defacto cultural architect. In this regard, many of the environmental puzzles, particularly those which require the use of machinery or are constituted with cultural relics, act as demonstrations of civil processes. Rarely do video games build lore this rich, or yet, so seamlessly into the fabric of the gameplay. Metroid is a narrative of few words, but with depth that many strive for.

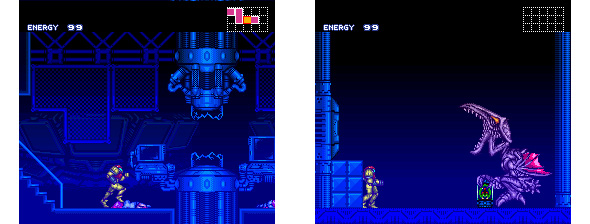

Tense atmosphere and the sense of isolation felt by the player are also tenets of the Metroid franchise. In Super Metroid, the title screen with the baby metroid in the jar establishes an almost complete absence of life. Again, the setting, but, more correctly, the sound is used as a device to control mood. Where many other games opt for busy noise, Metroid instead opts for controlled instances of silence followed up crescendos which build and create tensions. Moments where little happens, but much is felt.

Since the atmosphere, narrative and overall framework for exploration are harmoniously built into the environment and therefore the gameplay, Metroid is a franchise that stands as a testament to good game design. As Metroid‘s design is very medium-centric, relying on the factors that define video games (interactivity, adaptive environments), the franchise excels at conveying atmosphere, narrative and challenge to the player.

More obvious to mainstream video games folk is the fact that Metroid, through protagonist Samus Aran, champions femininity without sexualization or even glorification of the empowerment of women. Metroid, particularly Super Metroid – the title in question – has been a standout title for speed running, the art of completing a game in the shortest time possible. Overall then, Metroid is an eminent video game series, a series which fosters exploration, harmonious narrative and gameplay, atmosphere, works against the grain of video game gender stereotypes, yet facilitates dedicated game communities through speed running. And for all this, in the sense of the games themselves, Metroid is modest about its achievements which makes it all the more a champion.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99