Aria of Sorrow Review – Centralised Layout and The Tactical Soul System

November 5th, 2010

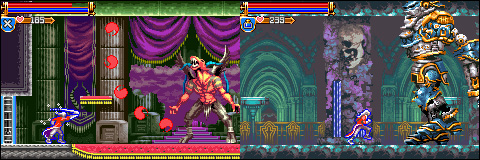

Aria of Sorrow is a fine improvement over Harmony of Dissonance. I razzed on Harmony of Dissonance for its incompetence at stringing the player from one major interval of gameplay to another. In regards to Aria of Sorrow, you never once stop to think about the layout and you don’t really use the map screen all that much either. You’re too busy whisking off to the next place on the map. Each subsection exit is the closest offshoot route to the entrance of the next which means that there’s minimal backtracking. Furthermore I didn’t feel the need to use a teleport once, whereas I used them more frequently in Harmony of Dissonance.

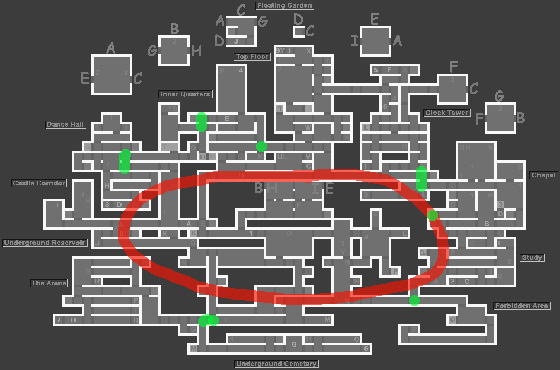

How is Aria of Sorrow such a dramatic improvement? Well let’s take a look at the castle layout.

You can see how each subsection (marked with their squished text titles) connects to a central part (red circle) which the player arrives back, rounding off the chunks of gameplay nicely. You’ll also notice that the subsections themselves are threaded together at various junctions (green dots), allowing for a smooth transition between nearby subsections without negating the overworld hub. This layout means that the player can be strung off to tackle more than one subsection at a time and then return, with minimal fuss, to the central hub and move to the next fresh chunk of gameplay.

What you can’t see on the map, however, is the complete overhaul to the ability system. In Aria of Sorrow there are more significant upgrades this time, including the ability to walk on water, walk underwater, become a bat alongside the regular double jump, high jump and slide mechanics. The former three are all a part of the new Tactical Soul System. These abilities act as devices to draw the player to the entrances of each subsection by interaction points as I described in my Harmony of Dissonance piece. Let’s be a little clearer by using an example though:

When the player begins the game, they explore the central hub area and come across areas that they cannot quite reach or parts of the game they can’t interact with. For the sake of this example, the water level near the entrance to the cemetery makes it impossible to overcome the high wall blocking the player’s path. The player takes a note of this and moves on. Later they will acquire the Undine ability which allows them to walk on water. Receiving this item and playing around with it will likely create a click in the player’s brain, telling them where to go next.

The more abilities, the more opportunities the game has to exploit this technique of letting the player realise their own path. Let’s talk about this Tactical Soul System, shall we? I described it on Twitter like this:

“Soulset [Tactical Soul System] is like the fusion system from Metroid Fusion, however, you can gain abilities from regular enemies instead of just bosses”

So, basically, when the player downs an enemy, there is a chance that they will absorb their soul thereby inheriting the enemy’s ability. There are 3 groups of souls (Bullet, Guardian, and Enchant) and only one soul from each group can be equipped at a time. Bullet souls are sub-weapons, guardian souls are similar to spells and use up magic for the duration of their use and enchant souls boost stats, while some offer temporary abilities (walking on water, for instance). The Tactical Soul System gives the player incentive to actively engage in combat and rewards them with new techniques which feed back into diversifying the combat. I’ve discussed this self-sustaining approach of rewarding players with more tools before in regards to Space Invaders Infinite Gene. In Aria of Sorrow it goes a long way into alleviating the grind that can occur through the mostly spammy combat. It’s a much more fleshed out than the sub-weapon drops plus elemental spell combinations of Harmony of Dissonance. The wide spread of equipable weapons, ranging from your traditional whips to axes, spears and even a pair of guns, is the other element of Aria of Sorrow which livens up the combat.

Conclusion

Aria of Sorrow addresses the castle layout issues of its predecessor Harmony of Dissonance by using a central hub to connect subsections together and avoid messy overlap in design. The core ability set has increased and works more effectively as a device to lead players from one area to another based on interaction points left at subsection entrances on the main hub. The Tactical Soul System, like in Space Invaders Infinity Gene, diversifies play on the players own participation and works effectively at reducing the grind that may come from combat. Overall, Aria of Sorrow is the better of the two games with cleaner castle design and a the Tactical Soul System which encourages the players to participate more with the combat, rewarding them with more tools that inturn make play more varied.

Necessary Aside for stuff that needs to get off my chest:What really irks me about Aria of Sorrow though is that 3 specific souls are required to see the real ending. Argh!

Additional Readings

Castlevania: Aria of Sorrow – Castlevania Dungeon

Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance – Castle Layout and Ability “Stringing”

November 2nd, 2010

My experience with Harmony of Dissonance can be summarised like this: it took me about a month of on-and-off play to complete Harmony of Dissonance, whereas I beat Aria of Sorrow in 3 days of solid play. My playtime was drawn-out in Harmony of Dissonance because of numerous road blocks which brought my playtime to a standstill.

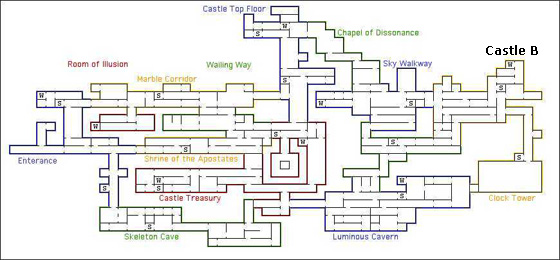

Harmony of Dissonance‘s castle, as you can see from the map, is a muddle of interconnected subsections (marked by their text labels) without a central hub to string players neatly from the end of one area to the start of another. Subsections effectively act as routes to other subsections bottlenecking progress and creating large amounts of needless backtracking. That is, if you need to get from the Sky Walkway to the Entrance, you must backtrack through 3-5 subsections depending on which route you take. It’s also very difficult for the player to mentally compress this amalgamation of play zones into a coherent order.

The player travels from the entrance to the (uppish) left of the screen to the point labelled “castle b” (they teleport between the 2 masses of areas), then back underneath to the entrance and finally to the central box. At any point in the game there is more than one path to take. This number doubles at the “Castle B” point on the map where the entire castle is duplicated and the player can switch to the slightly modified palette-swap version through special portals. Because of the large number of avenues and potential dead-ends for players, Harmony of Dissonance ought to utilise a combination of techniques to gesture players towards the right path.

The best measure for guiding the player in a Metroidvania game is to create a baiting system around the player’s not-yet-acquired abilities. You do this by starting the player off with only basic functionality, dropping interaction markers for not-yet-acquired abilities throughout the environment and then finally coughing up the abilities necessary to interact with said interaction points. The interaction markers (a grapple point, a platform that’s just too high to reach) plant seeds in the player’s mind which they mentally flag down, then once they obtain a new ability (grapple beam, double jump) and draw the connection between the new ability and the interaction point, a “click” goes off in their brain. They’ve done it! The player thinks that they are so smart for figuring it all out and rushes to where the interaction marker is (conveniently, the next part of the game) with haste. This is a tried and true design element of Metroidvania games.

Harmony of Dissonance only has 3 obtainable abilities to limit the player’s progression: Lizzard’s tale (slide), Sylph Feather (double jump) and Griffith’s Wing (high jump). Considering the game’s size, 3 abilities is far too few to string the player from one part of the game to another. Furthermore, there’s a very lax reliance on these already too few abilities. They’re only ever properly needed a few times throughout the whole game. Once at the junction point to the next area and then maybe a few times after that. Because there are so few interaction points in Harmony of Dissonance (and the nature of the upgrades mean that they can’t be made explicitly clear, ie higher platforms as opposed to a clearly defined grapple point), this stringing dynamic is hardly at all in play. An exception to this is the suggestion of a raised room on the exterior pathway to the castle, a seed that plants itself deep in the initial instances of the game.

Because the number of abilities is so few, Harmony of Dissonance uses some peripheral, inventory items to replace abilities as limiting factors. As these items are really just nothing more than added text in your menu, it’s not always easy to draw the connections between an piece of inventory and something in the environment which requires it. A key to a door is simple enough, but when a key is Maxim’s braclet and it opens a magic door, it gets tricky. And anyways, it’s easy to forget that you even have a key when you can only use it in the one instance. Other issues arise when you use a key to open a floodgate that you can’t find on the map, effectively asking the player to put the key in a random hole while the supposed flood gate opens.

Conclusion

Harmony of Dissonance demanded entirely too much of my time and patience due to a confusing left-to-right castle design and a lack of effective stringing through ability baiting. The castle connects subsections together like Lego and not to a hub-like core which reduces backtracking and unclear, overlapping design. The stringing proved weak because only a handful of abilities were used and they were stretched over the whole game. Furthermore, inventory items were occasionally used as weak replacements.

Additional Readings

Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance (2002) – Castlevania Dungeon

Castlevania Harmony Of Dissonance : Playing As Simon Belmont, Megaman And Mario

Or find someone else who can be critical…

October 29th, 2010

My twin brother is the vice president of the Game Developers Club at Adelaide University. Just recently he gave a presentation titled Meaningful Play to his peers and further posted the presentation up on Youtube. After watching his presentation, I buzzed him an email reviewing his theory on game design (which nicely falls into the first part of the presentation, below). You can watch the presentation here, here and here in its 23 minute entirety. For now though I have included the first part of the video and my response to it.

Firstly, I think it is dangerous to use a subjective adjective like “meaningful” in discussing games. Anyone can find anything to be meaningful. It would be better to discuss the game in regards to design and not include one’s ideas which are external to the game. This is something I have mentioned in my tweets recently.

By meaningful, I think you mean interplay. Your quotes from Rules of Play all allude to interplay but are put in a complicated way and fail to sharply address what the relationship is between reactions and gameplay. When you say things in your own words or use examples it’s clear that there is some confusion in your understanding. Here is a clearer quote for you of how games are meaningful:

“interplay is where actions and elements in a game aren’t means to an end, but fluid opportunities that invite the player to play around with the changing situation”

You can read a full description here with examples.

You’ll note your quote on the descriptive definition (slide) is similar to the quote I use in my post, but it goes a little further to add the “fluid opportunities that invite the player to play around with the changing situation”. Meaningful play is not simply that games react to the player (as your quote in the initial slide suggests), it is instead that the reactions lead to more interactions (interplay). And the more interplay there is between mechanics the greater depth and “meaningfulness” there is.

Your quotes exclude or aren’t clear on this point and so too is your understanding. For example, in the slide on the descriptive definition your own words say that the push and pull reaction between mechanics (interplay) allow us to understand the mechanics which are inside the game. This doesn’t say anything about the way reactions work to open opportunities for more interaction.

The evaluative definition is also very nebulous and doesn’t answer it’s own point . I would question your quote by then asking “and what is that then?” or “so what actually occurs?”. This quote is like saying, “chocolate ice cream is what happens when chocolate and ice cream come together” instead of “chocolate icecream is chocalate flavoured ice-cream”.

Your words here are again not so relevant to the quote.

The discernable part and what you then say about it irks me. How well the games makes the unfolding of interplay apparent is not a measure of how much interplay there is in a game. Putting it another way, lucidity!=a part measure of “meaningfullness”. And you certainly can’t use it as a quotient to compare with other games. Furthermore, how can we even compare the levels of interaction in an interactive medium with mediums that have no interaction as you say?

Intergrated is all fine though.

In the bullet point slide it’s clear that you are tripping up on this needlessly complex language.

The noughts and crosses board is actually a mirror and the pieces are halves. Not sure if you noticed that. In this example, you fail to discuss interplay and “discernability”. What you want to say is that when placing a piece on the board, wherever placed, this changes the game for the other player as they must alter their strategy every turn. This interplay is discernable through the representation of the pieces on the board in regards to matching three.

In your Tetris example you again don’t discuss “discernabilty” in regards to the outcome of the interaction/interplay/the terms and conditions of “meaningful play” (ok, no more “meaningful play” from here!) . That is, when you destroy blocks through making a tetris you see new block formations open up which creates new and different opportunities to interact (via your block placement). This is readily discernable as the player can see the visual structure of the collection of blocks and what happens when they remove them and the blocks rearrange.

Personally, I wouldn’t have used chess as the 3rd example as the interplay is similar to noughts and crosses (players pipping players with the position of their pieces). But more so as it actually subverts this whole notion of discernability through the “unknown implications” which you back-peddle on. You need to be clear and say that the fact that I move a chess piece and then physically release it says that I have completed the action. The releasing of the piece represents the end of the “move mechanic” and allows the players to therefore intepret moving as a mechanical feature of the system of rules that is chess.

What you say about the environment (level design?) isn’t so much about the environment itself as much as it is the things in them and how they effect the existing rule system. What you mean here is counterpoint. Again, another quote and another link:

“Counterpoint, in gaming, is a word for the way gameplay develops past optimization by layering interactive elements into a single gameplay experience. When each layer influcences, interacts, and enhances the functions/gameplay of each other layer the gameplay emerges into a medium of expression that reflects the individuality of a player and the dynamics that reflect the complexity of the world we live in.”

Basically, the way elements of games (enemies, time limits, exploding barrels) create ripples in the interplay. And here is an example.

The Killzone 2 example is a killer, but it should have been under the other heading as it has nothing to do with the environment/counterpoint and is actually about discernability (clarity is a better word, I think) and how it cushions the reload mechanic. Using the word “consequence” is a bad choice.

The Uncharted example is again a good example but it is more about camera angles as validation for chunks of gameplay than counterpoint which you asserted as “environment” at the start of this slide.

The last part on this slide about breaking rules makes no sense to me as your 2 examples weren’t about rules, but rather mechanics and camera.

The Mario slide is utterly confusing and full of holes. You ought to talk about the way the fire flower allows Mario to gun down enemies, Super Mario can break blocks and small Mario walk through tight places. These are all good examples of the integration (level design and mechanics work together).

However, I don’t like this term as tracking the relationship between mechanics, interplay and loads of counterpoint and level design is impossible to do without generalisation. Also certain parts have strong and weak integration respective of their strong/weak roles in the system of rules and mechanics.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99