Zelda: Twilight Princess – Conformity, Innovation and Relevancy

July 5th, 2009

After a prolonged on-off play through of The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess, one thing becomes remarkably clear about the whole experience. Twilight Princess ultimately strives and fails under the weight of its own legacy.

There are many prominent examples which I could use to substantiate my ideas. I’ll go with my favourite; the Stallord – ie. mega stalfos – boss from the Arbiter’s Grounds temple.

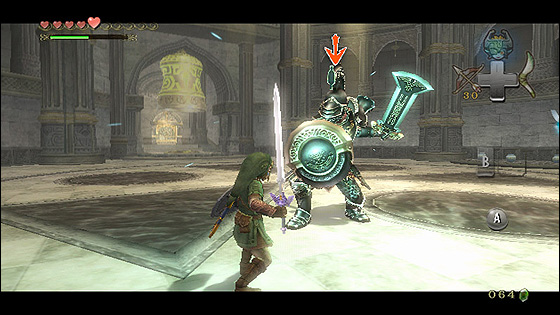

The battle begins with Stallord resurrected by the evil Zant. The creature rises then sits in the centre of a sand-filled bowel, raised only by a spine of individual bones, using his skeletal hands to support his hunch over the arena. The bowel is filled with sand which draws stationary objects away from the rim of the arena. Link uses his spinner to grind around the rim of the bowl, before launching towards the Stallord, with the aim of denting his spinal support in the centre. The boss soon summons legions of the undead to deflect and obscure Link’s spinner. The dynamic begins to play out as a sort of circular pinball machine with obstructions (the undead and Stallord’s hands) acting as bumpers to shield the spine from damage.

As with all Zelda dungeons, this boss battle works as an exercise testing the item-of-choice for each respective dungeon, in this case the spinner. It demands the player to apply their recently acquired knowledge of the device [spinner] to a practical example. As the battle unfolds and the means to victory becomes increasingly more elaborate, with a heightened number of obstacles, Link must appropriate his strategies differently in order to defeat the boss – the game incites the player to reconsider and reapply their former understanding of the game world.

This begins, as it usually does with the later Zelda boss battles, by first increasing the difficulty of the initial confrontation (ie. presence of undead minions, aggravation of the Stallord itself) before entering a second phase. Each phase requires a different problem solving technique.

It’s the design of these levels of elevation where Nintendo’s prowess comes into it’s own. The first scenario of the Stallord confrontation is concentrated in the centre of the arena – although Link twirls along the rim of the arena, the player is more conscious of their access to the spine. The player’s movement is also from vertical top to vertical bottom and from outwards to inwards, as Link glides into the base of the arena. They’re effectively using the spinner as a pinball.

In the second section, the sand sinks revealing a circular platformer in the middle surrounded by a waterless moat. The Stallord knocks Link down into the lower levels where Link must use the spinner to climb his way back to the top, before being interrupted by the creature’s floating head. Once Link leverages enough height he can transfer between rims knocking the head in the process. Somehow reminds me very much of the Cave of Wonders from Aladdin.

Here we see Nintendo applying an opposing design to the previous section, demanding the player to again re-adapt to the changing situation. The player moves from vertical bottom to vertical top and concentrates on the inner and outer rims of the moat, travelling left to right. By turning the arena on it’s head Nintendo have opened up a new design demanding the player operate on different axes of thought which inturn forces the player to think laterally as to how to complete the second phase of the battle. This time the spinner is instead used as a device to hop between surfaces.

These two parts fit together to create a very engaging and original piece of gameplay which engross deeply in the player’s mental approach to problem solving. The resurrection of the boss half-way through was, of course, a fitting surprise, but the way the game challenges the player through clever design logic which expounds the usage of the spinner is what crafts an overall challenging and enjoyable experience.

The memories that I’ll most take away from Zelda: Twilight Princess are the moments such as the above example, which are either cleverly designed elements or examples of pure creativity both implemented in a wonderfully Nintendo manner. Midna and the Twilight world, the original items such as the spinner, ball and chain and Bionic Commando-esque double hookshot, sumo wrestling with Gorons, snowboarding with a crazy Yeti, dueling Gannondorf on horseback, canoeing and the final few dungeons. These examples engaged me deeply and often made me laugh out loud at the pure ingenuity.

The more I continued to play Twilight Princess the more resounding this argument became in my head. Twilight Princess seems to be a battle between inspired and iterative capital. While not all capital borrowed from previous games is by any means bad, it is familiar territory, and for fans, a fair deal of it can be considered tired. This is no doubt exacerbated by the foundation of Twilight Princess‘ core which is -as the fans demanded- a graphically realistic, traditional Zelda experience in the vein of Ocarina of Time. Naturally, the fans aren’t game designers and their request is invariably different from their desires. The idea of a mechanically-considered sequel to Ocarina of Time (ie. not the direct-sequel, Majora’s Mask) is wrought with its own implications which defeat the prospects of a “proper” sequel. Games after all, exist within the times, and really what should be asked for is not another Ocarina of Time, no, the next Ocarina of Time – an Ocarina of Time we haven’t even imagined yet. Whether or not such a title should bear so much likeness to Ocarina is out of the question – “next” frankly doesn’t mean “same”. So maybe Zelda: Wind Waker is closer to a truer sequel than what some people might have originally believed.

A mechanically-considered sequel to Ocarina of Time – such as Zelda: Twilight Princess – is faced with numerous design challenges. Firstly the narrowing of the technological gap means that there isn’t terribly much Twilight Princess can do which couldn’t have been done on the N64, relative to the SNES-N64, and other technological jumps. The Wii motion control is the key exception here. Secondly, with more installments behind it, the foundation mechanics for the series were exhausted to a higher degree with the later Twilight Princess than with the earlier Ocarina of Time and Wind Waker, this demands an increased level of innovation in order to match the elevated abundance of increasingly laboured mechanics. Thus, Twilight Princess can ultimately be judged by fans on the disparity between inspired and tired capital.

A Brief Aside (Majora’s Mask)

Just a quick digression, I want to elaborate on my case using Zelda: Majora’s Mask. Majora’s Mask represents the converse choice to the traditional approach. The title takes the previous frameworks and twists it on its head to create a different play environment. Because the framework of the whole game is reworked, it naturally refaces the familiar content, in turn creating a refreshingly innovative interpretation of the series. For example, the Goron, Zora and Deku tribes are all staples of the series. Putting on a mask and transforming into either race, changes the way you are perceived by either culture. They respond to a Hylian very differently than one of their own and the dialogue reflects this. Further, you are now given access to the backstages of their sorted societies, which open up unique gameplay scenarios.This reinvigorates our already familiar understanding of these tribes and injects it with different angles, interpretations and information.

Back to Main Article

The reason why I care so much about the scales of innovation is because it determines the overall quality of the games, but perhaps more importantly it is proportional (or at least heavily skewed by) the relevancy that franchises such as Mario and Zelda have within the video game industry.

As you’re likely already quite familiar with, the uprising of western developers in recent years is threatening to make Japanese developers – and Nintendo’s big three – continually less and less relevant. Take the following example, back late last decade the boss battles in Ocarina of Time were considered the most intense seen in the industry. Fast forward some years and we can see a marked difference between say a Zelda: Twilight Princess and a God of War. In the years since Ocarina of Time, such studios as SCE Santa Monica have been honing their craft, a craft which – generally speaking – appeals strongly to a western audience. Last year’s E3 presentations, a pissing match between Sony and Microsoft as to who can offer the greatest sense of scale is largely indicative of that.

If we then revisit the Skullord boss battle and contrast it against, say, the Hyrda battle opening the original God of War (2005), the disparity in theatrical quality is vastly different. Whilst, Twilight Princess is no slouch theatrically, it pales in comparison to the finely executed God of War. Clearly in the span of a few years, these folks have literally gobbled up prime real estate which the Big N use to occupy. On the flipside, the Skullord is much more elegantly designed and in that sense can be considered superior, it all depends on tastes.

When it comes to Ninty domination, not only are we talking theatrics and dramatization, this is happening on many fronts; Nintendo’s key franchises are fighting to stay relevant and in my mind, Twilight Princess represents Nintendo grappling with that, slouching a little – it’s the embodiment of all this drama. Zelda, Mario and Metroid are the oldest classics in the book and they need constant reinvention to stay fresh. While Twilight Princess is the strongest embodiment of series ideals, it’s also the largest, most endearing Zelda title which are the reasons cited as to why it’s the best in the series. The clash between old and new, exhausted and fresh material represent a stumbling block in the series, as it waits for the next round of revolutionisation, but as with every title in the series, it represent something. It highlights that Nintendo should not become complacent with reusing familiar material as many have inferred the company doing so with Twilight Princess. In a sense, one might argue that fan’s wants ultimately dwarfed the series as despite it’s weaker content, The Wind Waker was a thoroughly more adventerous and innovative title than the conformative Twilight Princess.

This isn’t a cause for alarm though. If we can take anything out of this year’s E3, it’s that these western developers are now in pursuit of Nintendo’s innovation, they want to taste the success that trickles from the river of great ideas. Nintendo have forged their own trail, remarkably so, Twilight Princess (much like the Gamecube) is therefore the stepping stone required to reach that path. It’s representative of the state of Ocarina of Time in 2006. Evokes many ideas of where the series will go next, eh?

Additional Readings

Inside Zelda [Twilight Princess] – Zelda Universe

Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time Guest Review

June 29th, 2009

Wrote a review on Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time (PS2) for Video Games Blogger, you can find it here. Ferry, the editor over there, spliced a few game quotes between my copy.

I haven’t written a review for a long time. I usually feel rather apprehensive about writing them, since mainstream reviewing usually doesn’t gel with the flavour of discussion I have here. Readers seem to be conditioned by the lazy graphics, sound, gameplay checklist which usually only serves to affirm or negate their prior assumptions with little supportive evidence. This is fine – if you’re looking for it, but such a style fails to serve the wider market of potential consumers who aren’t already on the cusp of buying, looking for that affirmation.

I enjoy reading reviews where the writer justifies their assertions through supportive evidence and analysis, this allows readers to gain clearer insight into the game. The task of assigning adjectives and percentile grades to presentation, gameplay and sound does very little for the reader. Anyone can grade the visuals and sound from a trailer and/or screenshots, or read about the features of a game on the back of the box or in a press release. Without insight, the writer is almost useless – which most of them are.

It surprises me how this broken system doesn’t seem to be so harshly to older games, which is why I enjoy writing about them. I think I covered most of what I wanted to say on Sand of Time in my review. The platforming is delectable and the narrative a breath of fresh air, of course, I explain my point in the review, so please take a read. I’m playing through the trilogy, so I’ll likely have additional reviews once I finish the other games.

Additional Readings

Opinion: Do Video Games Over-Egg The Epic? – GameSetWatch

Retro reviewing – Retronauts Blog

Play Impressions: Kirby’s Dream Land 2 and Half-Life 2: Episode One

June 25th, 2009

Kirby’s Dream Land 2

There’s honestly very little to say about Kirby’s Dream Land 2. All you need to know is that it’s a black and white skinned Kirby title using the same template as Kirby’s Adventure. Because of this Kirby’s Dream Land 2 feels more like a sequel to the polished NES classic than the Game Boy original, and manages to individualize itself well by introducing three peripheral characters. Those characters – Rick the Hamster, Kine the Ocean Sunfish and Coo the Owl – cut in and out of the adventure and work as appropriate substitutes for a number of consumable abilities absent from Kirby’s Adventure. Since your animal friends layer on top of whatever ability Kirby has on hand they do add another tier of complexity to the title. Team this with a series of hidden rainbow pieces in each level (which open up an alternative ending) and despite it’s loftier hardware, Kirby’s Dream Land 2 is expanded enough to form a more than competent sequel to Kirby’s Adventure which, considering the polish of Kirby’s Adventure, says a lot. Other familiar tropes of the series are kept in tact such as the wonderfully characterized introductions preluding each world and mix of familiar characters.

The one thing that Dream Land 2 lacks (colour) can be compensated for on the Super Gameboy. Like Pokemon and Donkey Kong, whacking Kirby’s Dream Land 2 into your Super Game Boy will give the game a unique colour scheme different from the default swatches. Supposedly there’s some added spiff elsewhere too, not a bad deal if you prefer playing it on a TV. I played it on both.

Lastly, it’s nice to see Nintendo fix the disparity between the boxart graphic and in-game designs with this title. Kirby’s Dream Land 2 in this regard matches the game wonderfully, instead of appearing like an attempt at realistic abstract.

Half-Life 2: Episode One

If Half-life 2 were put to VHS, then Episode One would be the extended long-play. In a nutshell it’s more of the same gameplay from Half-life 2‘s later half, delivered in a remixed fashion with greater emphasis on set pieces and Alyx who now accompanies you throughout the 5-6 hour experience.

One might think that her part as a co-operative buddy might work in as another gimmick to colour the vanilla base of the series – in the same way that vehicles, ant lion bait and the gravity gun operated in Half-life 2 – unfortunately her presence surprisingly affects the core gameplay very little. You don’t need to babysit her much at all. She rarely dies, always follows you and can hold her own in a gun fight.

So what exactly is it that makes Episode One all that great? As discussed previously, the framework requires some sort of gimmick to make itself interesting, so what is it this time? Well…there isn’t really any prominent tricks, per see. What Valve deliver is a greater emphasis on improved moment-to-moment confrontations, teamed with a remix of some old mechanics from Half-life 2. Fundamentally the game offers very little new material, yet it’s approach to general gameplay is greatly overhauled. In Half-life 2, the game gave you an instrument (antlion bait, vehicle, gravity gun) and then pushes you out into a landscape largely composed of filler – it’s like you have to make your own fun. In Episode One, the wide lose-yourself-in-them landscapes are replaced with tighter quarters which is mostly dominated with more interesting segments of gameplay. Filler is now the glue between the action sequences rather than the other way around. Examples of these sequences may include a scenario where the lights go out while you need to survive an onslaught on zombies, where Alyx covers you as a sniper while you barge on ahead, where you see the gravity gun to grab falling debris there’s even a similar set piece to the cascade resonance from the original Half-life. Compare this to walking/driving around for extended periods of time to stumble upon an enemy camp, shoot a handful of Combines, zombies or Combine zombies and then continue walking around in the middle of nowhere. It’s easy to see in which game the fun lies?

This new found emphasis on moment-to-moment gameplay also serves to break down the chapterized feel of the game. In Half-life 2, each chapter sported a gimmick and stuck in the player’s mind as a series of compartments which the game organized as such. In Episode One, that structure shifts to a more scattered approach, relating to individual moments more so than instruments. This makes the title, although short, feel more endearing and continuous. Unlike Half-life 2 I have a difficult time ordering the events of the game. Valve have in this sense changed to way we consume the game.

Overall though, it can be seen that Episode One should be evaluated on the moment-to-moment action. While it does provide an assortment of interesting sequences which maintain a high enough pace, Episode One flounders in the end with a lame squad shifting exercise and a shortsighted boss battle. Furthermore there’s nothing much in Episode One that wasn’t in Half-life 2, which is disappointing. The best part is ultimately the re-evaluated approach, by spreading emphasis between gimmicks and confrontations, this gives Valve greater design leverage. Episode One does a good job at capitalizing on this, but not enough so to overcome what I believe to be Valve’s persistence to make these games realistic to the point of uninteresting. It’s a more accomplished and organised title, no doubt, but it’s a game in transition.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99