Technology, Mobility and Level Design in Quake II

September 14th, 2010

Quake II, as we’ve established of most genre-defining FPS games, is marked by its relationship to technology. So in order to understand id’s paradigm of technology creating and limiting FPS gameplay, let’s examine influence of technology over gameplay in Quake II.

Unlike FPS games a few years after its release, Quake II could not rapidly track small body parts in fast motion, namely the head, meaning that, without insta-kill head shots, shoot outs were longer and with only a limited number of AI at the one timze. id supported this technical dictation by ramping up the amount of damage which the player and their Strogg foes could sustain, thereby extending the duration of gunplay and making Quake II a game of manoeuvrability within arena designed levels.

(This design also works in well within the technical constraints, in that quicker deaths would require greater supplementation of enemies and therefore an increased likelihood of more enemies on screen at once, that of which the game couldn’t handle in a 3D environment. Furthermore, more hit points gives narrative credence to the Strogg’s being made of metal and other industrial fibre. By limiting the complexity of confrontations, the intelligent AI had a platform to be noticed).

But what do longer shoot outs mean exactly? Well, it means that standing still and firing off rounds of ammo won’t do much good. You’re rival will be acting likewise—and they’re designed so that once they lock-on they shoot liberally, never mind that they won’t run out of ammunition either—and you’ll both be running out of health which you can’t afford to do, so dodging, ducking and hiding become essential devices in overcoming enemies and defeating the game. The systems of shooting and movement support this type of environment and movement-centric play. Movement, for one, is quick, fluid and an advantage that you have over the slow, predictable enemy movement patterns in the game. There is also no reloading required whatsoever in Quake II and ammunition is plentiful which itself practically asserts the unimportance of arms in lieu of tactical use of the level design. Furthermore, there is no real tactical advantage in shooting certain body parts, so there’s little advantage in standing still and being too precise.

Initially, in the early levels of Quake II, which are less like a labyrinth and more open-ended, the player only needs to focus on their proximity to the foes around them. In later levels, where players are drawn into a series of arena-esque levels, the player must keep their distance while also leveraging the environment to exploit the weaknesses in the sophisticated (but decidedly predictable) enemy attack patterns. So, the levels are built to suit this type of play also.

(Backtracking from how technicality affects play behaviour and into how it affects other parts of the game. Similarly to Resident Evil 4, Quake II limits it colour palette to increase technical efficiency elsewhere, namely the fluid movement and steady performance. Also, it is the technical ability (and inability) of Quake II which structures it as a series of connected channels, bound by a level structure).

Conclusion

id established the first person shooter genre under the paradigm that technology creates game design. Quake II is an id first person shooter whose design is dictated by its technical ability and inability. As such, Quake II scales the shooting to only a few combatants at the one time and therefore emphasises the principles of mobility and tactical skills within the well designed levels.

Extended Readings

Coelacanth: Lessons from Doom

Super Metroid – Open-ended Linearity

August 31st, 2010

The original Metroid has a defining flaw that would later be rectified with its successor, Super Metroid. The open-ended environments are a composition of arbitrarily posted tile sets with little sense of direction. To put it frankly, the desolate planet Zebes is a maze. As a result, there’s a certain sense of dread you often feel when playing Metroid, as it’s very easy to lead yourself astray in the oxygen-less solitude and find yourself boxed in against an insurmountable tangle of similarly-looking tiles. Super Metroid avoids the confusion by providing sufficient scaffolding to lead players along without arousing their suspicion that the experience Super Metroid offers is a well managed, staged affair. In this way, it fools the player into discovering things for themselves, when in fact our exploration is preordained, and we love it all the more for it.

Let’s take a squiz at how exactly Super Metroid appears more open-ended than it actually is. Super Metroid utilizes the SR388 overworld as a hub which connects the player to the various planetary sub-sections. Overworlds are often interpreted as de-linearating a game and offering player choice, even though oftentimes they afford no such freedoms.Super Metroid‘s overworld is a guise. Players are free to search for and enter SR388’s separate domains before the game requires them to, but on stumbling upon Brinstar, Norfair or Maridia the player quickly realizes that their progress is limited by their current selection of power-ups. In this sense, the player’s sphere of progression is not tied to the seemingly open world, but to the power suit. Therefore, the limitations enforced upon the player are not presented in a way which can be translated into tangible areas of the map, by which, the player cannot properly understand what is or isn’t within their reach. The only way that they can find out is by looking for themselves. Not only does this unknown (but never hidden) factor liberate the player’s sense of exploration, but it also persuades them to gain their own bearings of the world through actual exploration. The map is therefore a clever aid in the exploration process, since it does provide that tangible reinforcement to the player.

The individual chunks of terrain that break away to your power-ups are doorways masked as environmental puzzles, where the power-ups themselves are switches that activate the opening of doors. When a player acquires a new power-up in Super Metroid, several gates are open. Of course, Super Metroid is still linear since the gates that lead to to the next major power-up (and so on until the end of the game) are pre-determined; all players will walk the same rough path. However, Super Metroid hides this very fact in three ways. Firstly, the player may take their own route to the next mandatory gateway. Secondly, when a power-up is gained, it opens the potential for the player to access peripheral weapon upgrades (which increases the number of items held), think of them as secondary doors. And lastly, on occasion, there is more than one mandatory gateway that leads the player to the next power-up; since there is some choice, this is thereby not linear. As you can see, it’s all effectively linear, but it’s mapped around a system of diversion. No first time player will stumble upon the perfect combination of clues to lead them linearly to the end of the game. Players will inevitably be de-routed, and on their way, stumble into weapon upgrades, dead ends, previously explored areas, and walk in circles; all are tricks to create a false sense of freedom.

So, the real meat of Super Metroid are the power-ups and respective gateways which forward the progression to the end game. These are directive tools which manipulate the player’s progression. And as can be seen, Metroid is highly managed, yet we love Metroid so much because the game tricks us into thinking that we are exploring by ourselves; however, we are exploring within the confines of a mold which is ultimately linear and intentional.

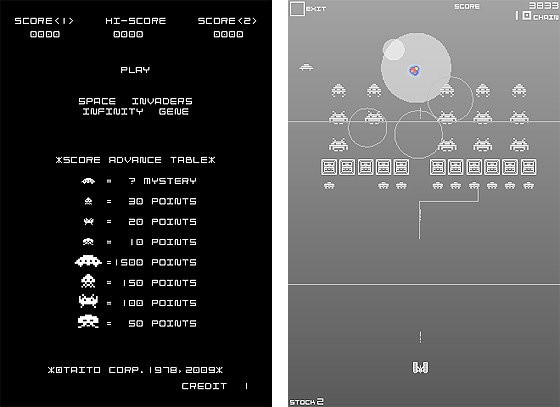

Space Invaders: Infinity Gene – Construction of the Shoot ’em Up

August 28th, 2010

Since popularising the shoot ’em up in 1978, the Space Invaders series practically went dormant for thirty years. Sure, Taito rolled out sequels and anniversary editions, but rarely did these games evolve the series in any meaningfully sufficient way. Such thinly-veiled cash-ins on the Space Invaders namesake could barely meet the legacy they were supposedly representing. The series’ presence in modern gaming was an embarrassment, to be sure. In recent years though, with the release of Space Invaders Extreme and its sequel, Taito have done good on one of gaming’s longest surviving brands by doing what they failed to get right before: tampering with the source.

In this light, Space Invaders Infinity Gene isn’t so much an expansion of an already great game like Extreme, but instead a tribute; an interactive construction of Space Invaders‘ legacy: the modern shoot ’em up. And it all begins from stage one, the original Space Invaders, before moving into progressively more contemporary territory.

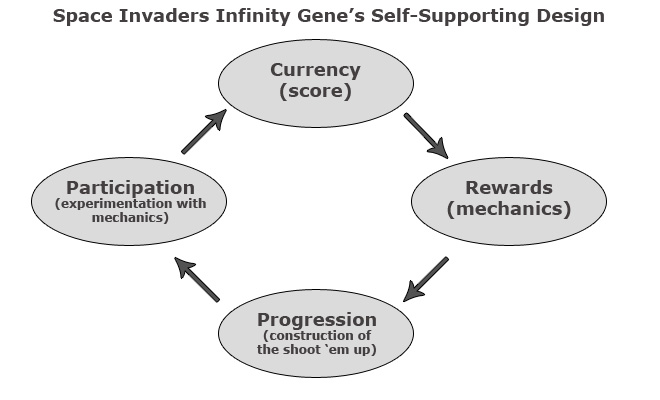

Like most age-old shoot ’em ups, in Infinity Gene, the player increases their score through a combo system. However, after completing a stage or losing a life, you’re not presented with a high score table, but instead the points earned act as a currency which fill out an evolution meter. Once you’ve maxed out the meter the game “EVOLVES”. Evolving adds one of three things to Infinity Gene: new mechanics, bonus stages or graphic and sound unlocks.

Replaying a level, which you are free to do at any time, will give you another shot at adding more blue juice to the bar. As you progress it becomes harder to score the points necessary to evolve, meaning that repeated plays slowly become a requirement of pushing the mechanical game forward. Yet ideally—and particularly in the later stages—you don’t want to be spending your time replaying the same level repeatedly just to gain an extra inch of blue fill. You do, however, still want to max out the evolution bar since the pay-off for doing so will make life easier by adding new gameplay mechanics. The result is well-crafted baiting, but calling Infinity Gene a game of baiting would be to do the game a great disservice. Points are gained on the grounds of skilfully employing combos and hitting targets (although you can grind if you need to) and the rewards are new tools which feed back into the loop of gaining points. The more points you earn, the more “arms” (shooting techniques) are made available via a selection screen preceding each level, giving the player more applicable options in meeting the challenges of the changing level design. So, experimentations and commitment leads to rewards which foster more experimentation and commitment. By commodifying the traditional points system, Infinity Gene’s gameplay becomes more relevant to regular players (as opposed to high scoreboard chasers) in that it facilitates a system of progression tied to the context of the game (evolution). Of course, high scoreboards are still present for those who wish to pursue them.

Once players make it through the initial comfort stages, Infinity Gene switches up its enemy patterns to suit the different “arms”, persuading the player to first explore with their new tools. Later, experimentation become mandatory as the design moves into a tertiary phase where only certain arms are applicable in defeating the enemy patterns present in each stage. This sort of involving level design which motivates the player to be creative with the tools they are provided with leads back into the currency of points. The more the player understands the various arms, the better off they are for gaining high combos and claiming a better score which they are in-turn rewarded with more tools.

Speaking in the ethos of the game itself, Infinity Gene is a construction, where the player constructs a modern day shmp, piece by piece, through their committal to the scoring system (the very foundation of the arcades, also part of the ethos). In Infinity Gene the means support the ends as can be seen in this diagram:

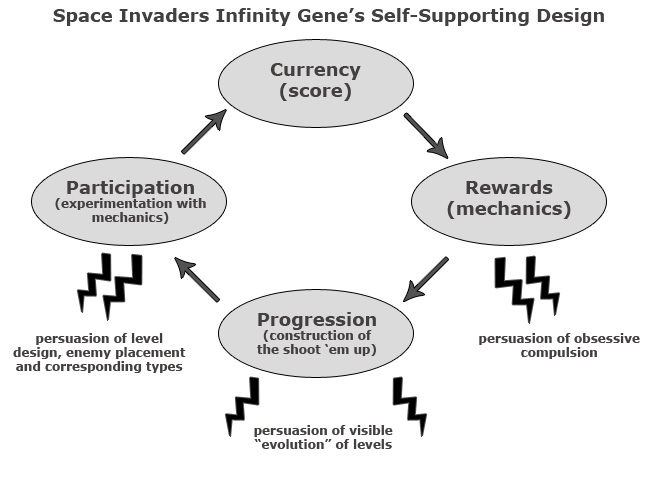

Now let’s add some squiggly lines:

It’s worth explaining the squiggly lines in the diagram. They are the underlying methods of persuasion used ensure the player remains active within this framework. Firstly, to the far right, persuasion of completism is the human tendency for no stone to be left unturned. This is the reason why Tetris is so addictive, our cerebral matter craves order in a world of clutter. Tetris creates clutter, the player creates order and the two forces create an addictive dynamism. Infinity Gene feeds our obsessive compulsive nature via the user interface of the level select screen. The main levels are mapped out along the spine of an evolution tree with 2 branches possible at either side. Since the player can only evolve once per stage, the interface keenly marks all the evolutions which have yet been reached, enticing the player to correct the apparent mistake.

Secondly, the centre point, the player is made to believe that the game is evolving (even if they themselves are not personally evolving the game very much) through the minor visual details added to each progressive level. Level-to-level, nuance forms around the crusts of the visual design, until a set of stages are completed and the presentation reboots with new colours and effects.

Lastly, as the player progresses, the layout of the levels (which transition from blank emptiness to more structural as you go along) and enemy placements begin to favour a wider variety of “arms”, nudging, and at times forcing, the player to actively use the tools in which they’re unlocking.

A Conclusion on Conclusions

Concluding the analysis here, I can’t help but comment on the most effective part of Infinity Gene: the ending. After building up Space Invaders through the lens of Gradius, R-Type and the bullet hell sub-genre, among others, the game ends, the credits roll and then suspiciously, after the dust settles, a variant of the original Space Invaders loads up with a lone invader rapidly making its descent to the bottom of the screen. Immediately, the tactile feeling reverts back to 1978, you’re power-ups and arms are removed and the game changes completely, leaving you with a sudden point of comparison. This game about evolution devolves to the base value in order for its magnitude to be understood. Personally speaking, the impact felt at this point validates all of the play up to that stage.

Conclusion

Space Invaders: Infinity Gene isn’t trying to make up for 30 years of cruddy ports, but rather it’s a documentation of the shoot ’em up genre during the period of time the self-proclaimed “KING OF GAMES” went intro retirement. Infinity Gene is a successful title, because it takes us on a journey where we meaningfully construct the results of a legacy left abandoned. The guts it takes to do this is commendable, but the execution is even more so.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99