‘Giving the Context’

February 5th, 2010

When writing any sort of game evaluation (preview, review, analysis piece, critique, etc.), the writer begins by explaining how the game works or what happens in the game. This is what I’ll call ‘giving the context’. As much as ‘giving the context’ is an essential component for this type of writing, it’s often the least interesting part of the article for both reader and writer. Sadly, the majority of evaluative articles consist almost entirely of context and share little insight with the reader. This is why we often moan so loudly over reviews; the reviewers rarely justify their comments with explanation and the readers therefore become suspicious. (Alternatively, the readers don’t read and become suspicious anyways).

The reason why context is boring to read falls in line with similar comments made by Jim Gee in his book Good Games and Good Learning. Players don’t learn how to play a game by reading the instruction manual—no one ever looks at the manual if they can help it, they just jump straight in. People learn the rules of a game not by reading about it, but by playing. Reading an instruction manual or game review in the pursuit of understanding the operation of a game is counterproductive, because it’s difficult to learn anything through static text alone.

I’m sure that you’ve probably met this frustration before, most likely through school, but more to the point, after reading a review and yet still not understanding the fundamental rules of a game, let alone why it’s good or bad or is worthy of your green paper. (Perhaps this is why video reviews are now so popular; they inherently provide continuous context throughout the review). I’ve certainly felt this way many times, just recently after reading several reviews on Bioware’s two most recent games: Dragon Age Origins and Mass Effect 2, I still have no grasp on the core gameplay, particularly in Dragon Age. I think it’s about time I ought to just play the games for myself.

Personally, I believe that as writers it’s our job to make this mandatory part of the job as quick and effective as possible, so that we can get down to the business of giving meaning to the game through our critique, analysis and observations.

Anyone can—and does—write the synopsis of a plot or explain what happens in a game, provided that you’re a sound writer, giving context is pretty easy, analysis, however, is the most difficult part of the job which is why analysis it’s often the part which is most lacking. Therefore, the great majority of games writing serves very little purpose beyond condensing manuals or expanding PR bullet points into sentences, because that’s what naturally comes easiest.

On an side, I think this also explains why it’s difficult to have an engaging conversation with other people about games. Good games discussion requires one of two things, preferably both: 1) shared knowledge of context and evaluation (hopefully at a rather deep level) 2) the mutual patience required to listen to someone explain a complicated rule system to you through spoken language and then evaluate the rule system. It’s really tricky, as I’m sure you all know which is why most discussion amounts to “wasn’t it cool when…”.

One of my goals this year is to trim down the amount of context in my ‘Game Discussion’ articles. Of course, I want it to remain sufficient, just in fewer words, if possible. So as a footnote to this article, I’ve written a list of measures which I hope to adopt in my future writing, this may also be useful for you too as either a critical reader or a writer. If you have any further suggestions, I’d be happy to hear them, so please leave a comment in the box below:

- Use as few words as possible to convey as much information as possible.

- KISS ? Keep it simple stupid, people have to make sense of what you’re saying, try to stay away from esoteric or abstract language.

- Use language (particularly verbs) which stylise mechanics and other integral parts of the game which can easily be stylised. These improve readability and understanding, and also make the writing more palatable.

- Or if you can’t do the above, make up your own verb to describe an action rather than continuously using 3-4 words to describe a single action or event. This avoids repetition.

- If there is a similar game or gameplay style which is adapted into your game then refer to it. eg. Gears of War style shooters, Geometry Wars clone.

- Be specific and accurate. Saying ‘an arena shooter’ saves on having to explain that it’s a shoot ’em up in a box.

- Use images and video of the gameplay itself. This is the easiest method for setting context. If you’re going to jump straight into analysis, assuming that the audience is already immersed in the game, then maybe a video review from Youtube or Gametrailers would prove useful.

- Dot points or diagrams are also a great idea Critical Gaming is a wonderful example of this technique, and in fact is the ideal example of a context-minimal, analysis-rich blog.

Pixel Hunt Re-examined (+ Some Words on Retroaction)

February 4th, 2010

![]()

Back in April last year I heavily criticised endearing Australian multiplatform games magazine, Hyper, while simultaneously throwing praise to side-line act Pixel Hunt. Pixel Hunt is worthy comparison to Hyper. I mean, it’s free, conservative games writing brought to you by Hyper contributors with enough leeway to go rogue without the uncomfortable snapback of their part-time employers. In particular, I commented on Pixel Hunt’s skew for a more progressive, supposedly analytical approach to games writing.

My comments were made under the observation of the magazine’s steady progression towards a more feature-rich, analysis-heavy format that could, in a few issues, develop it into an authority, you know, something worth repeated reading in this competitive field of non-commercial games writing. Unfortunately, I feel that since then the promise has disappeared as the magazine settles down into a familiar template. Yeah, I’m sure you know the one.

![]()

Don’t get me wrong, I agree with the comments made by Dylan Burns (editor) in his opening editorial to issue #10 “Our team of writers is, I believe, amongst the most passionate in this country”. They’re talented too. Really clean writers which I appreciate, even though it’s not my most preferred style as a reader. Yet despite all the talent and good writers they house, the format is suffocation.

I’m kinda tired of harping on the inherent flaws of the writing format adopted by the enthusiast and professional media alike (you’ve probably heard me talk about it before, anyways), so let’s just bang out a list, it’ll be easier:

- Pixel Hunt is bloated by an unhealthy number of reviews

- 85-95% of the content in each review tells the reader what happens in the game rather than explaining how the game is good/bad or how the game achieves a desired effect, what effect the game had on the player or just any general insight, some reviewers are better than others in this regard

- Considering the late release of the magazine in respects to rival formats, marketing, demos and the release of the games themselves, most readers are likely to already know what happens in the game, and considering this part constitutes the majority of the magazine’s content, there is little reason to bother reading it at all

- The amount of space given to the editorials is criminal, which is why they all cover very simplistic arguments

- The features are the magazine’s primary selling point* and more attention needs to be paid here

- Most of the writers sound the same (this is obviously subjective, Hyper has always suffered the same problem, I feel)

None of this is designed to offend, but rather explain my own discontent with the magazine, because I believe that it’s capable of much more. Hmm, let’s take another online magazine, Retroaction, as a counter example to Pixel Hunt:

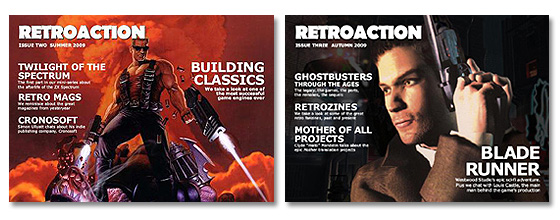

Retroaction is a new, retro/indie games e-magazine run by a handful of retro game enthusiasts, most of which have little writing experience. Although the quality of writing has improved in leaps and bounds since the first issue (they’re up to their 3rd, so far), it’s still downright atrocious at times. Furthermore, Retroaction’s reviews are almost entirely full of information with very little evaluation to speak of, and most of the appraisal is glowing or at least generous. Did I mention that the layout and visual design leaves a little to be desired too? Yet despite the lacking amenities, I often come back to re-read articles in Retroaction because they’re original and therefore insightful, even within the retro/indie games niche. A two part feature on the ZX Spectrum’s Russian knock-offs and resulting indie development scene over the past 20 years is not only interesting, it’s material that can’t easily be found anywhere else. A lack of analysis in the reviews isn’t imperative to Retroaction, unlike with Pixel Hunt, because the information, the “here’s what happens in the game part”, is sufficient on its own, because the games themselves are largely unheard of in the mainstream**.

Conformity does not equate to incentive and it’s for this reason, for Pixel Hunt’s pursuit of the status quo of enthusiast writing, that my interest (and prior recommendation) has diminished.

On the other hand, I hope that my criticisms haven’t dissuaded you too much, because as it turns out I actually contributed an article to the latest issue (issue #10, download here, 38mbs). With a dash of irony though, I was wrongly credited. (And no, before you ask, the error didn’t spur me on to write this piece). I wrote the article on Dragon Quest IV at the end of the magazine, NOT Daniel Golding. You might know Daniel as the guy who gained rapturous attention after mapping out the self-important “Brainysphere”. You could’ve fooled me though, as I read half way into the article before realising I’d written it myself, and there I was feeling envious and all, shucks. I’m surprised though, honestly, it really blends in with the rest of the content, which is strange given that the nature of the writing isn’t usually part of my shtick. So check it out for that reason, or to spot the unedited spelling error…

*Can it be considered a selling point if it’s free? Probably not. Either way, the features are generally good.

**I’m starting to understand now why the majority of blogs in my RSS feed reader are retro or alternative-based. Conventional games writing is simply that (however, it can be analysis-rich AND progressive, as is the case with much of Eurogamer‘s content, for example), and even within the bloggosphere, good analysis is scattered, whereas the retro and alternative coverage is often always interesting.

“Become Genuinely Interested In Other People”

January 14th, 2010

If I were to run my own bookstore, I’d probably re-title the ‘Self-Help’ section to ‘Common Sense for Foolish People’. Generally speaking, there are three flavours of self-help books: weight loss, depression and success/motivation. The answers to each dilemma is very simple, but often made complicated by the people dealing with the problem:

Need to lose weight? Eat lean, exercise more. Feeling depressed? Make friends, adopt a positive attitude. Want success? Find a goal and work hard.

As you can tell, I’m pigeon-holing the entire genre, and I apologise for doing so, however, the primary ideas behind self-help books can be rendered moot in the face of common sense. Well, that’s my belief. Self-help books primarily serve the purpose of reminding us to be sensible when we’re likely to over-evaluate an issue. In anycase, to remedy my ignorance towards the new age crowd, let me talk about a self-help book that I’ve been reading: How to Win Friends and Influence People.

My brother, who does engineering, suggested that I read this. He originally began reading How to Win Friends and Influence People because good communication is a key requisite of team engineering, of which constitutes most of the field. He didn’t suggest that I read it because I lack people skills…but because it’s such a good book! A classic in fact. Yes, it’s all common sense, but damn, we sure do lose sight of common sense easily.

Allow me to demonstrate with one of the principles which transcends the very subject matter (yes, this does have something to do with video games, bear with me): “Become Genuinely Interested In Other People”.

Human nature states that 90% of the time we’re thinking about ourself, right? Putting ourself first is essential to our survival, pretty much. What Dale Carnegie (author) asserts is that by being genuinely interested in other people, we’re appeasing their interests and therefore can’t help but be liked ourselves. Think about it in practicality, who wouldn’t be friendly to someone who expressed a genuine interest in themselves? In a sense, people who put other’s interest ahead of their own are playing people for what they want, and winning. That’s a very selfish way to talk about a very no selfish act, I suppose.

This notion of serving the customer can not just lead to good interpersonal relations but also to success in other areas. Allow me to elaborate with two examples:

Mac

I’ve had my Macbook for about one month and it’s easy to see why Apple has such a strong fan base. Mac computers are designed for being used by normal human beings (yes, normal human beings), the user is central to the design and not the company. This is why Mac hardware and software is aesthetically very pleasing, why they don’t receive viruses, why the AC lead is magnetic, why the trackpad is almost as good as using a mouse: these are all features that make the experience simpler and more pleasant for the user. It’s because Macs pander their users that Apple fans get so aggro over issues like DRM, where Apple is (was?) clearly violating its users.

Windows, on the other hand, has the stigma of being unfriendly and very corporate/power user-centric. Consider the types of responses you hear from Windows users when discussing operating systems. They all say the same thing, they hate Windows/the computer but have no choice but to stick with it. Furthermore, Windows and Windows software (Office, for example) is also heavily pirated, because it’s perceived as not offering value. (Aside: Why would you buy MS Office when you can get Open Office for free).

Although Macs only hold a small market share (for obvious reasons being that Macs are overpriced and lack compatibility), the market share is strong and dedicated and less likely to convert to Windows or Linux. If Microsoft continues to neglect regular users and Apple continues to treat its users well, it seems likely that the market share for Mac computers will slowly increase.

Nintendo

Nintendo have always been successful at developing video games, particularly over the past few years, as usability is of prime importance to their design philosophies. Take a game such as Wii Fit, Wii Fit is actively interested in the player’s development and reinforces the player’s growth through the trainers which give personal, positive advice and praise which is sincere and unflattering.

Nintendo also design their games so that rather than forcing players through a mandatory, you’re-a-newbie tutorial, the environment embodies the tutorial and teaches players organically as they progress. In effect, it empowers the player and masks inability. Super Mario Bros. for instance, does not sit the player down and tell them in writing how to play, the logic of the entire game world is conveyed in the first few seconds of play as the goomba walks towards the player. If the player jumps over or on top of the goomba, they continue playing, that’s the tutorial: jump to avoid obstacles. Metroid achieved the same effect; walk left instead of right: exploration. Super Metroid iterates on this again by presenting players with an initial roadblock in which the only way players can progress is by bombing an unsuspecting part of the landscape. The message? Check everywhere, without fail. Super Metroid is unwavering in its commitment to this principle and magnificently iterates on the concept while placing itself on step ahead of the player, which is why Super Metroid is one of the most acclaimed video games ever made, it respects that the player and believes that they are capable of overcoming the challenge.

I’m sure that you can think of many counter examples, but here’s one in case you’re unsure. Yesterday I booted up my brother’s PC and started playing Runman: Race Around the World, the acclaimed indie title which is free and worth downloading (do it!). Runman’s an excellent game for fans of speed running platformers, however it’s tutorial components could be streamlined even further. Instead of having a sign telling the player to press ‘X’ to wall jump when standing in front of several adjacent walls, all they need is a picture of an ‘X’, the players can fill in the rest.

Nintendo games treat players with respect and sincerity which makes them approachable and enjoyed by many. It’s the reason why they’re been on top of the business for almost 30 years.

Conclusion

As we can see, Dale Carnegie’s principle of becoming genuinely interested in other people is effective not just in relationships, but in a corporate and design setting also. Companies that are aware of their user base and appease their user base through product and promotion (Capcom’s recent effort with Dark Void is a great example) will always be successful ones. Looks like common sense, and self-help books for that matter, prevail in the end, maybe I’m not such a hater.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99