Video Games as Cultural Symbols in the Global Cultural Supermarket

March 28th, 2009

I read a paper a few days ago taken from the first chapter of Gordon Mathews’ book Global Culture/Individual Identity – you can read the first chapter on Google Books (albeit with pages torn out). In the paper he dissects the two core definitions of culture; the traditional anthropological definition as “the way of life of a people” and the more progressive model of culture as “the global cultural supermarket”. Surprisingly the latter definition was completely new to me. On digging around the references it made sense as to why. Mathews had pretty much invented this term himself, although in the references he acknowledged previous examples on where the concept was touched upon briefly by other authors.

I don’t usually cross check references in such a way but this time I felt compelled to not only because the metaphor makes it easy to comprehend a particularly complicated issue but also because it’s such a very workable definition. Hardly perfect of course, as Mathews himself points out, but an interesting lens in which to view the subject matter.

The basic definition is that our consumerism defines our culture, the products we buy, things we consume are as Kathryn Woodward would say symbols of our identity. The global cultural supermarket is a vast database, but full access is privileged unfortunately, and this is one half of where the definition falls short. The cultural supermarket works well only within the model of modern affluent society. It doesn’t particularly cater well for lesser developed countries where the complete range of products within the supermarket is limited. Mathews slices this as being a flaw of the definition, I liken it more to an inherent issue that is part of the definition itself. Geographically the same issue exists as well, where geographical distance limits access, something Mathews didn’t actually touch upon.

The other weakness in the definition is that sometimes our consumerism within the market has no bearing on our identity. An example from the text is an American women who feels that she is of the wrong blood, so each week she eats sashimi, learns Japanese art and religion, all in the pursuit of being “the Orient”. While her involvement is governed for her lust to become Japanese, others participate in such activities purely for interest or simply because the food taste good – it plays little to no part on their concept of self identity.

Video games, like any form of consumer goods exert their own impressions of cultural identity, at least within the players mind. There’s something that has to be has to be said about fans of niche Japanese developers such as Altus, Nippon Ichi and SNK. Games consumerism is representative of culture, buying certain games and being an enthusiast of that flavour of gaming makes us appeared cultured to that respective origin.

You might be forgiven to think that I’m referring strictly to country culture (ie. culture as per the “the way of life of a people”). Where as in the case of the previous example, I’d be suggesting that players of these games would be in pursuit of the Japanese cultural identity, or at least the Japanese enthusiast/fan identity. This isn’t the only case, although it could be (again this refers to the second flaw). Players of those games may in fact be enthusiasts of the culture and identity created by the consumers of such games, I’m talking about fan cultures. Think of such purchases as aligning oneself to a particular fan culture/following.

These cultures are all multifaceted too. My previous example is by no means absolute. That is; playing games by those developers are not the fixed requirement of belonging to the culture of “Japanese wannabes”. This system is variable, and differs among tastes and interests. This is the crutch of the super market, of consumerism; you can pick and chose, accessorize if you will, or in less tainted terms create your own cultural identity through mixtures of different cultural symbols.

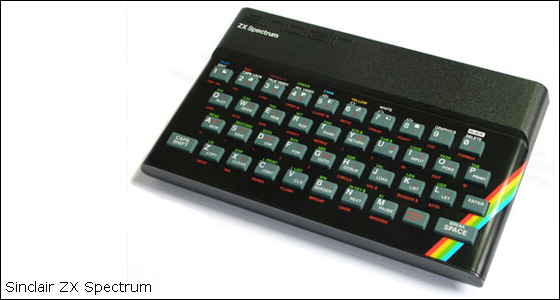

One last example to highlight the flexibility and divergent nature of culture. This time I’ll choose the symbols the Dizzy series, Sinclair ZX Spectrum and Rare Ware. These symbols are obviously synonymous with the 1980s through to early 1990 retro gaming scene in UK. Hence they fit under a variety of cultural spectrums: video games -> personal computer gaming -> the UK -> 1980-1990s era. And if we change one of those symbols to say the Commodore 64, the spheres of cultural influence shift again. Not to say that our original selection can’t be interpreted differently (because it can as well) but that on the whole the cultural effect of each piece is very vague. Every combination and each piece are culturally identifiable in many different interpretations, hence what they offer our identity is equally up for interpretation.

Perhaps I faltered with the last example, I don’t know. Whatever the case, you can see how games operate within this idea of the cultural supermarket. I’ve also used the concept as a vector to demonstrate how slippery it is to categorize and brand culture by relating it video games and Kathryn Woodward’s idea of cultural symbols. I hope it made some sense to you.

Ingrained Japanese culture and handling of Chinese Ethnicity within the Metal Gear Universe

March 25th, 2009

Lots of Metal Gear Solid spoilers, and a pretty deep look into the lore, so you’ve been warned!

***

This post was originally going to be about how Solid Snake is a terrible representation of an American born Chinese, but on going over my fact checking I realized that he is actually Japanese/American, surrogated through a Chinese mother (EVA).

I was a little dumbfounded at this revelation when watching the video that re-affirmed this for me (1:50). Mentioning of the Japanese egg donor (IVF process) seemed a little suspect, as it just appear hammed in there. I mean, it appears as though the developers simply wanted to clarify and cement the fact that Snake is actually Japanese, and not of Chinese ethnicity, the latter which would be an easy assumption given the events of MGS3, EVA’s titular title of Big Mama and how she openly states that she is Snake’s mother.

I can see how this was perhaps needed to justify the lines of Vulcan Raven in MGS1, but it does feel very self conscious of itself, that Snake is not Chinese. It really wouldn’t matter either way but consider these two previously glossed over points:

Mei Ling’s odd representation in the later half of MGS4. As I’ve mentioned before, strange, nonsensical, award sexual innuendo that makes her appear unexpectedly ditsy, particular in contrast to her more respected role in Metal Gear Solid. I just find that these two identities don’t match at all.

As I also lightly discussed earlier on this blog, EVA has no hints of being Chinese. No accent, blonde hair and unmistakably western appearance. In one of the games she justifies this (I honestly can’t recall, nor find it) but the justification that an archetypal, western Bond Girl is actually of Chinese ethnicity is a terribly hard sell.

These three ultra subtle clues, suggest some minute, no doubt culturally ingrained influences that have naturally flowed into the development process of this game. I don’t raise these points to be in any way contentious, rather, they make an interesting example of the way in which culture naturally affects video game development, as it would anything else. That we should be conscious of these hints, because, while seemingly insignificant, they are very important in the grander message.

Yakuza 2: Institutional Knowledge and The Virtual Classroom

February 25th, 2009

I want to continue discussing Yakuza 2, but in a different frame of mind. Back in my article titled What I Learnt From A Stone Frog Spitting Coloured Marbles, I took the underlying principles of a post by Iroquois Pliskin regarding the way in which games teach players and adapted it to Zuma’s ball flinging frustration. This time around, I’d like to adapt the same idea (the process of how games teach us things) to Yakuza 2.

You’ll remember that in my previous entry I discussed a certain event in which I went into a bar (of sorts), chose a lady of my choice and then proceeded to eat fruit and drink beer with her while she probed me with cute questions. The whole premise of this place was completely foreign to me, as I mentioned in the post; Australia doesn’t have such places…well at least to bounds of my knowledge*.

As foreign as it was I found the whole excursion to be extremely refreshing in a way that a lot of games aren’t. Obviously the “wow, they do this shit in Japan” factor was in play, but so too was the education of “instiutional knowledge”.

As the name suggests institutional knowledge is the knowledge gained by someone who has interactions with an institution**. For example, I go to work and I know which door I have to enter in, how to swipe my card, how to speak to my superiors, how to avoid them when I want to, which people to suck up to and which people to leave alone etc. Institutional knowledge is something that is rarely taught, rather acquired over time. It’s like street smarts for an institution. Institution then can be define in many ways and not just the ones build on concrete and cement. Institutions can range from banks, restaurants and hotels to group seminars, friend relationships and catching public transport.

In the example of Yakuza 2 the game allows the player to acquire institutional knowledge on multiple instances. In fact, the gamey parts of the institutional interactions (you either select product/service, walk around or leave) to a certain extent ensure that it’s taught. Their choices provide you with some light contextualization. With this said there is enough opportunity for both realization and education of institutional knowledge within these environments.

For instance, at the bar place (it’s called Prime BTW) the game drops you into a situation where you must eat and drink. Your enthusiastic partner will ask you to select what you wish to eat and drink, with your choices affecting how well she likes you – incidentally determining if she’ll want your company again*** . The game turns these activities into smaller games which both teach and allow institutional knowledge to be self-educated. The verbal requests by staff colour the purpose of the institution, the way the staff and your lady friend respond to your requests allows mastery of knowledge to be slowly acquired. You soon figure out that buying the cheapest booze never makes her happy, or that accepting extra time results in a higher bill at the end.

Being a game set in a foreign culture, the cultural aspects layer on top of the institutional knowledge. Each country has institutions and the way that participants operate in those institutional contexts change based on cultural norms. For example; the cultural divide between the get-to-know-you-first Chinese and seal-the-deal Western trade approaches, as documented in this paper.

Yakuza 2, being a game set in an overseas, day-to-day commodity environment not only teaches the player institutional knowledge, it shares the wisdom of Japanese institutional knowledge. Everything within Yakuza’s institutions are affected by Japanese culture; the way people react to you, the rules of the institutions etc.

So what’s the point of all this then? Well, consider this. Institutional knowledge is difficult to teach, it’s something gained solely through experience. Think of any company doing business in the increasingly global market, a local business dealing with migrant customers, multiple ethnic types in the work place etc. When dealing with any intercultural context these things matter! If a video game can teach a player not just institutional knowledge, but also that knowledge in an overseas context, then there is clearly more merit here than just entertainment value.

That’s the end of the post. I did just want to include a short ranting post script too, it’s slightly detached from the main piece though.

Within the niche of foreign language and culture, the concept of the virtual classroom has been discussed at lengths with the dominance of references pointing to online life-sim Second Life. From my observations of other people’s experiences, Second Life is quite a rudimentary and troublesome medium which relies on pre-made tools and the online attendance of participants. Particularly with different time zones, the prospect collapses in comparison to the breadth and depth seen in Yakuza 2.

Yakuza 2 in reference to the virtual classroom is by no means a perfectly just relation. The upsides include greater detail and attention to authenticity, the flaws come from the lack of pre-set educational elements. Whatever the case, the argument can be made that Yakuza 2 also succeeds as an educational tool for Japanese context and etiquette.

*If I had Powerpoint installed on my machine I would load it up and dig out some references to justify this nonsense.

**Maybe we do? I do think that if we did, the “after hours service” connotation would perhaps be less discrete, making it a different place. I don’t know, I’m not a Yakuza!

***Yes she gave me her email!

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99