The Decline of Super Monkey Ball

November 25th, 2016

“Because you’re asking ‘Why? Why are they in the balls?’ With this story, you’re going to find out why they’re in the balls.”

—Marty Caplan, Producer of Super Monkey Ball Adventure

Back in 2006 fans and critics universally panned Super Monkey Ball Adventure labelling the game as the first misfire in the series. Given quotes like the one above, it’s not hard to understand why. In hindsight, Super Monkey Ball Adventure‘s failure signalled the series’s decline over subsequent games. Yet for all its flaws, Adventure was a spin-off from the main series developed by an external studio trying their hand at a new concept. The game is far removed from the main line Monkey Ball games and their developers in Japan.

Rather I would argue that Super Monkey Ball‘s decline began from the second game in the series. Super Monkey Ball 2 added fast-moving objects, big drops, and mazes to the pool of precision-based challenges. Dr Bad Boon and songs about poo aside, the game’s new-fangled story mode defocused the gameplay through its do-what-you-want organisation of level challenges. Super Monkey Ball Deluxe, a greatest hits spin on the first two titles, only added to the bloat with 43 new levels—a middling compilation defined by expansive mazes, flat gimmicks, and few fresh ideas. Not helping matters the lack of the Gamecube’s octagonal grooves in the PS2 and Xbox analogue sticks diminished the series’s iconic precision input. Super Monkey Ball Adventure may have been the punching bag, but the series’s real decline started three years earlier.

Chaotic Approach to Levels

Super Monkey Ball Deluxe consists of two types of levels: tight navigational challenges which test the player’s ability to finely manoeuvre their monkey ball to the goal and ineffective gimmick levels which hinge on risk or chance. The latter group tend to feature the following elements:

Sporadic jumping challenges and fast-moving objects which can knock the player off stage with little notice. The combination of the default behind-the-monkey camera angle, slow camera tracking, and fast movement speed inhibit the game’s ability to frame the action when the player quickly turns, falls, or makes a sporadic action. Unfortunately, some levels are constructed so as to elicit such perilous manoeuvrs.

Mazes and dull switch puzzles. Given the default camera position, the player cannot easily see above walled areas. Thus without the information necessary to make informed decisions, most mazes boil down to guesswork. Some mazes spread themselves out for no apparent reason other than to force the player to move through a highly scaffolded environment.

Random stage conceptions (for example, a giant wall textured in the Monkey Ball website address or an insect walking along a cylinder) instead of challenges designed around the navigational nuances of the game system.

To substantiate my argument, I’ve compiled a list of the worst offending levels from Super Monkey Ball Deluxe. Most examples have a video link, so you can click through to see the level played out in full.

Levels with Fast-moving Objects

Levels with Bad Puzzles

Crazy Maze 9-9

Levels with Big Jumps and Falls

Levels with Poorly-implemented Gimmicks

In challenge mode the player cannot filter between the navigational challenges and ineffective gimmick levels, rather the two types are mixed in together. As a result, the effort you invest in manoeuvring through the obstacle courses can easily be undermined by the chance involved in many of the gimmicky stages. Furthermore, the luck involved in these levels also promotes a more reckless style of play which the player may transfer over to the dexterity-focused navigational challenges. These non-serious challenges can therefore have a potentially negative impact on player motivation and concentration.

Organisation of Level Challenges

Super Monkey Ball 2‘s story mode defocuses the gameplay by giving the player too much control over their progression. For each world the player must complete ten out of a pool of twenty levels of varying difficulty. The selection screen includes difficulty rankings for each level and players can choose to complete whichever levels they like in whichever order they like. The player therefore has an unprecedented degree of freedom over the experience, being able to scale the difficulty as they see fit. The extra freedom sounds good on paper, but in reality the average player lacks the aptitude and strategies to successfully regulate their own learning.

Regardless of one’s experience with a particular series or genre, players simply don’t know what the next set of challenges will look like, let alone what conceptual understandings or skills they’ll need going forward. If I were to trust someone to teach me a game, I would probably trust the people who made the game over myself, the novice. And so it is that the freedom to play whichever level one wishes should actually read as “the freedom to drive the difficulty curve off a cliff”.

If there’s one consolation, the level select does allow players to skip past the problematic levels discussed above. So in the end I personally didn’t mind the extra leeway.

Camera Design

Super Monkey Ball Deluxe‘s camera is perfectly functional for most stages, but can prove troublesome for particular types of challenges. The camera sits behind the monkey ball and doesn’t like to move from its default position. If the ball turns, the camera will maintain its original reference point. This behaviour keeps the camera work clean and non-intrusive. Once the player releases the stick, though, the camera will swivel around the monkey ball until it arrives back in its default position. The rotation begins at a reasonable pace and then slows to a crawl as it comes in for landing behind the monkey ball. The player therefore controls the camera through intentional releases of the analogue stick following a turn.

The camera—privileging the default position—will sometimes end its rotation before it arrives behind the monkey ball, leaving the player to contend with a slightly skewed perspective. I’m not exactly sure if this issue is related to the release, the turn, or something else—but it exists nonetheless. The speed and responsiveness of the camera’s tracking exert an “invisible” but powerful influence on Super Monkey Ball‘s gameplay.

The camera’s behaviour is crucial in 3D navigational games like Super Monkey as the camera establishes the nature of space. Super Monkey Ball employs a tracking camera (as opposed to say a series of specifically programmed cameras as in, say, Super Mario 3D Land), and so a significant element of play involves aligning the camera, monkey ball, and path ahead. By triangulating these elements, the player can simplify a game challenge.

The video above demonstrates what triangulation looks like in action. The player moves the monkey ball directly in front of the tightrope. They then attempt to cross the narrow bridge as the camera is arriving in behind the monkey ball. This is a brazen move. Although the monkey ball is dead ahead of the tightrope, the camera is skewed at an angle making the challenge harder to read cognitively. The camera then arrives and the player fails to recalibrate causing them to slip and fail the challenge. The player messes up the second go. But for the third attempt, they wait for the camera to move into alignment. Then all they need to do is push the analogue stick forward and keep a steady hand. As this example illustrates, the camera defines the nature of space and by extension the difficulty of the challenge.

In levels where the player must turn 90 degrees or more, the camera becomes a source of great frustration. 90 degree turns require a significant realignment of the camera and the player often cannot afford to have the perspective off at an angle. As the topmost animated gif so neatly demonstrates, the player makes an input and then waits 5 seconds or more for the game to provide feedback—all the while the timer continues to count down overhead. If the camera then decides not to arrive directly behind the monkey ball, the player must re-attempt the turn (tilting away from and then towards the tightrope) as they wrestle the camera into place. Something as simple as lining up the camera can feel like you’re fighting your way out of a perpetual state of flux.

Additional Comments

- In story mode, the player can retry stages as much as they like. No threat of failure means no pressure on the player to concentrate and play well. Without anything on the line, I found that I tended to play more recklessly.

- Story mode contrasts strongly with challenge mode, a rigid series of successively more difficult courses. Even though challenge mode squashes story mode’s problematic freedom, I still wish the difficulty incline were more forgiving. The level variation also doesn’t prepare the player for some of the game’s trickier manoeuvres. If stages were organised more tightly around level concepts (curves, tightropes, stairs, bowls, etc), then the player’s learning would be more focused and they would better be able to commit new learning to memory.

- The textures in the PS2 version are horribly grainy and the load times in the stage select menu and between levels are atrocious. The Gamecube games look clean and have seemingly no loading times. The practice menu offers the same functionality as the stage select, but without the bad loading times, so I suspect that the PS2 has a hard time reading the miniature 3D models of the stages into memory.

- The octagonal barrier around the Gamecube’s analog stick make the Monkey Ball games easier to control as they lock the stick in place, extremely useful for rolling in a straight line. On the DualShock, though, the round barrier makes it easy to slide off angle.

- To play Super Monkey Ball well, one needs a strong synchronisation between body and mind. The last thing you want is to be distracted by a vibrating washing machine or steam from a giant pot…but alas, the misadventures of Dr. Bad Boon.

[Originally written in 2014]

Additional Reading

Super Monkey Ball – Leading into a Banana Blitz

God of War: Chains of Olympus Photo Diary

November 18th, 2016

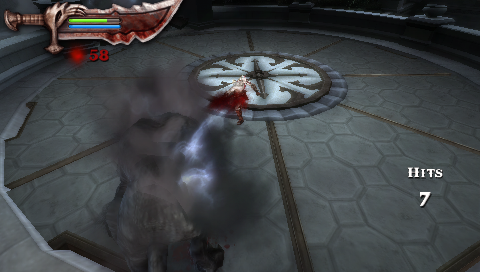

Thanks to the wonders of custom firmware I recently equipped my PSP with a screen capture plugin. All I have to do is press that useless music note button and—snap!—a screenshot is saved to the console’s memory stick. So I thought I’d take my new camera with me on my vacation to Ancient Greece. Below is a selection of happy snaps from God of War: Chains of Olympus.

This first boss battle eschews God of War‘s typical raised viewpoint for a behind-the-avatar perspective. Kratos therefore attacks into the screen, with his body obscuring some of the action. By bringing Kratos and the Basilisk into near visual alignment, the player also can’t easily judge the distance between the two combatants and read and respond to incoming attacks. We see this kind of camera design in 3DS games like Super Mario 3D Land, where the hardware helps the player read depth. Games designed for 2D screens tend to use clever visual devices to communicate depth (such as Resident Evil 4‘s laser sights). Unfortunately, in this instance the player lacks any clear visual aids or markers to assist them in reading the action. With the lines of communication obscured somewhat, each attack is made with a degree of uncertainty and guesswork.

Our tour guide Kratos meets with the king of Persia. Although the king swings his sword around in 3D space, the hit box only covers the horizontal plane. The player can avoid many of the attacks by jumping, even as the king’s blades appear to hit Kratos.

The front-on viewpoint (and blurring effects) makes it hard to judge the depth of the fire balls.

This photo demonstrates the incredibly generous range of Kratos’s grab (which in this case was unsuccessful, hence the recoil). When successful a long distance grab looks extremely unnatural in action.

The two flailing enemies on the far left had just taken arrows to the back. By moving to the side of the line of archers, I was able to get them to fire into one another. Although this trick might make the archers appear brain-dead, friendly fire is a great asset in action games as it can lead to cool emergent scenarios born out of higher level play (like the one in the photo). It’s a shame then that friendly fire only applies to archers.

The foggy appearance of these wolf enemies clutters the visual space with wispy smog making it harder than necessary to recognise the incoming claw attack.

The camera in the first room of The Cave of Olympus stands in a raised corner and swivels to track the movements of our muscly tour guide. As Kratos moves towards the camera, it peers downwards and walls in the perspective. As he moves away from the camera, it tilts upwards to capture more of the action. Despite Kratos being some way from the camera in this grab, the environment is still squashed into the frame. The PSP’s widescreen format and lower screen resolution have implications when bringing console-based franchises over to the platform (much like the GameBoy’s NES adaptions). This room is an example of the developers not quite being able to work around those limitations.

As we press a button, we tend to apply more pressure over time in the same way that Kratos heaves harder as he is just about to open a chest. The direct synchronisation between tactile input and in-game animation makes chest opening a pleasant interaction. It would be neat if these moments had a skill-based element (like a timed trigger) to give the player more buy-in.

Kratos can visibly fit through the gap, but an invisible wall prevents him from doing so. Why use artificial measures when you can just have form fit function?

The Sun Shield, Chains of Olympus‘s variant of the Golden Fleece, is my favourite weapon in the God of War series. The shield allows Kratos to block enemy attacks. If the player guards right before an attack makes impact, they can reflect the attack, turning the defensive manoeuvre into an offensive strike.

Helios Reverse, the melee counter, stuns nearby enemies, giving the player a narrow window of time to land some free hits. The wider range of the counter facilitates higher level play. When an enemy enters the first few frames of their attacking animation, the player can quickly reposition Kratos next to other enemies so as to catch them within the stun’s range. Assuming their successful, the player will then have free reign to lay into the surrounding enemies as they stand around stunned. This higher level technique involves quick reading of the enemy states, a heightened spatial awareness, and the ability to predict future outcomes.

Helios Flash, the melee counter upgrade, has a strong knock-back and helps the player separate enemies and gain advantage in the tug-of-war struggle over spatial control.

Helios Reflect, the projectile counter, allows the player to “catch” objects and fire them back at the sender. Given that Kratos’s only ranged attack (the Light of Dawn spell) appears late in the game, the Helios Reflect plugs a significant hole in Kratos’s ability set (attacking distant enemies).

The Sun Shield’s set of mechanics emphasise a more considered approach to combat (observing and reacting to openings). The back-and-forth interplay is a welcome reprieve from beating up mobs of pawns who can barely fight back.

The Sun Shield is paired with Hell Soldiers, demonic grunts who sprint towards Kratos and strike him. As soon as they’re cued in to attack they’ll raise their swords which is a visual prompt that tells the player they have a limited amount of time to stop what they’re doing and prepare to dodge, block, or shield stun. These disruptors force the player to shift their focus between immediate and distant stimuli and switch up their play style accordingly. Archers and Fire Guards play a similar role in combat.

As the player enters the Temple of Helios they climb past this door. When they need to leave they exit through it. The God of War games often use visual markers to elicit curiosity, give the player some time to forget about it, and then bring things full circle. It’s not Super Metroid, but it’s neat nonetheless.

The shadow communicates that it’s safe for the player to release Kratos’s grip on the handhold. I don’t think anyone minds fake lighting when it communicates useful information.

These enemies spawn out of thin air. It would have been more natural if they were waiting for Kratos, descended down the rock face, or crawled in from the sides.

This long narrow path is used to create anticipation through the player’s inactive-state.

Another example of how friendly fire can lead to emergent, higher level play. The archer followed Kratos’s movements with his bow and took splash damage after shooting the magic arrow into the ground in front of them.

This wall looks breakable, but isn’t—at least not yet.

Kratos and I thought that this area was a little odd. As far as we could recall, the God of War games never place enemies next to save points. These Hell Soldiers therefore weaken the legitimacy of save points as secure safe havens. If the player saves the game in the midst of combat, it’s not clear whether the battle will resume or be reset when they reload the game. Furthermore, if they save on low health just before an enemy’s hit makes contact, the latter situation could be problematic. It’s for these reasons that games tend to isolate save points from regular gameplay.

One cannot help but worry they’ll break the PSP’s flimsy analog nub when tasked with these QTEs. In this scene Kratos obtains the Gauntlet of Zeus, an alternative weapon to the Chains of Olympus (pretty significant given that this is a combat game, right?). It’s a pity then that we’re nearing the end of the game at this point.

The old drag-the-enemy-carcass-onto-the-switch puzzle. I wonder why he didn’t disappear into thin air like his mates.

Charon’s scythe has a much longer range than the Blades of Olympus, so the player is forced to use the Sun Shield to create openings in the attacks. The Blades of Olympus give Kratos a significant range advantage over his enemies, so it’s neat that the game effectively took this power away from the player and put Kratos in a similar position to the grunt enemies.

God of War’s narrative would be more cohesive and effective if the designers tried to express meaning through the core gameplay (combat) instead of through these narrative vignettes. In God of War III each boss Kratos defeats has an effect on the game world which is present through various shifts in the environment (for example, killing Poseidon causes the world to flood). As the player works their way towards the end of the game, it feels as though Kratos’s rage (as expressed through the player’s actions) is causing the destruction of the Earth. The problem with this short, QTE-led narrative vignette is that it’s divorced from the player’s actions throughout the game and the piece of themselves the player has contributed to the experience. As such, this scene has limited narrative pay-off.

Every time the player loses against Persephone’s first phase, they need to climb these stairs and watch the same minute-long cutscene again. It’s good that the player is given time to think through and internalise their mistake, but this is overkill.

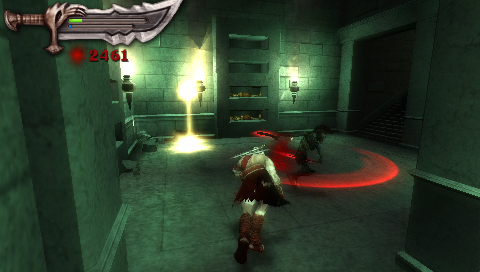

In the second challenge room I always stand along the centre of the back wall so as to limit potential attacks to 180 degrees around Kratos. At this point the camera also offers the widest view of the arena.

[Originally written in 2014]

Recommended Reading / Viewing

God of War III – Graphical Attrition (Daniel Primed)

God of War III – Kratos: Villain, Anti-Hero or Indifferent (Daniel Primed)

God of War III – Ending Analysis (Daniel Primed)

God of War III – Secondary and Peripheral Mechanics Analysis (Daniel Primed)

God of War III – Primary Mechanics Analysis (Daniel Primed)

God of War II – A Review (Daniel Primed)

God of War – Unearthing the Legend documentary (YouTube)

God of War – Game Directors Live (YouTube)

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99