Diner Dash and Interactive Capitalism

December 20th, 2010

Diner Dash is such a fascinating title to me because of its simulation and critique of capitalism in the food industry. Before we get to that part though, we need to first examine the task list and combo system which define Diner Dash‘s core gameplay.

Overview

In Diner Dash you play as restaurant-owner-cum-waitress Flo starting up her own business venture. The main goal is rake in more and more customers in the pursuit of earning more money and therefore expanding the franchise with additional restaurants. I played the iPod version as seen in the video above. You can try a demo of Diner Dash here. Otherwise there are versions for the Steam, WiiWare, PSN and other download services.

Points of Interaction

Diner Dash is a single screen game, all points of interaction are labelled in the screenshot below. There isn’t, however, a snack stand in this screenshot. As you can see by the labels, it would sit right next to the drink dispenser. Snacks come into play in the later levels of the game.

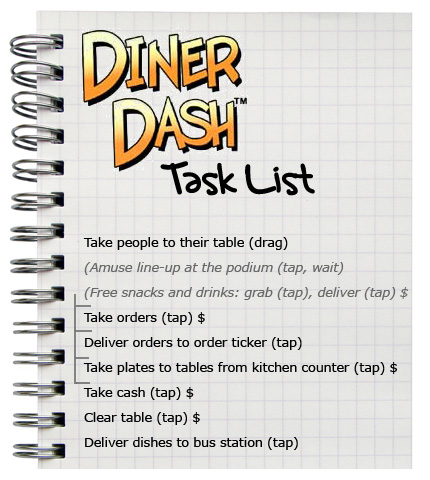

Task List

All interactions in Diner Dash are based around tapping or dragging. Such simplicity means that there is little to say about the mechanics other than the input method suits the action quite well. For example, dragging customers is to lead them to their table, tapping is to pick up or unload something. Diner Dash is about the mastery of procedure (the tasks involved in the running of the restaurant) and not the mastery of core mechanics. So let’s first start by observing what is required of Flo to fill the bellies and floss the wallets of customers.

The greyed text are non-mandatory actions. These interactions can be used to control the flow of customers, keep them happy and avoid any combo interrupts. We’ll get to this stuff later though. For now, notice that snacks and drinks can be given to customers at anytime while they are sitting in their seats. Also note the interactions marked with dollar signs. Cash is gained each time the player does these $ actions (not including colour matching). The video below demonstrates the bare bones process:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a-5fccghRPw

3 Ways to Multiply Your Money

The goal of Diner Dash is to obviously make money, but simply sending customers through on it’s own isn’t enough. There are 3 abstract systems which add or multiply you score. That is, how much money you can earn. These systems become increasingly more important as the money (ie. point) requirement in each stage increases.

Hearts

As you can see by the screenshots, each set of customers has 5 hearts floating above their head which represents their level of satisfaction. The quicker you set them down, take their orders and deliver their food, the more satisfied they will be. When the customers come to pay for the meal, their tip is dependent upon the number of hearts, so you want to get the job done quickly.

The screenshot above shows the different states of the customer throughout the process. When the customer is either lining up, requesting an order, awaiting food or ready to pay the bill, an invisible timer will be counting down. As the waiting time for the customers increases they become visibly agitated, before finally losing a heart of satisfaction. If a set of customers wait too long their hearts will decrease until they storm out in anger, cutting a chunk out of your profit.

Hearts can be replenished by giving the customers free drinks or snacks or talking to the them while they wait in front of the podium.

Different types of customers become impatient at different rates or more or less impatient when in certain states. For example: Mr. Hot Shot. These types of customers can wait patiently in line but have no patience when it come to being seated.

Colour Match

You may have also noticed that the customers and chairs are coloured. If you match the customers wearing certain coloured clothing with the respective coloured chairs then you will gain $100 for every match. An additional multiplier on the base $100 is added for every consecutive same colour, same chair match thereafter. So, for example, match the same colour 3 times in a row and the cash goes up to $300.

(Actually resorting the arrangement of set customers as you’ve got they over the tables is incredibly finicky on the iPod. You might have a group of 3 customers with one wearing red, actually shifting him onto the red seat requires some random sliding on the spot. Play First would have been better off automating it, so that the game chose the best matches for the player).

Repeated Actions (Action Chain Bonus)

As we know, for each $ interaction money is added to the player’s piggy bank. This amount of money is doubled if the $ interaction is repeated. For example, maybe 2 sets of customers enter and are seated, you take the order of the first set and gain $20, then you take the second set and gain an extra $40. This reward system is called an “action chain bonus”, which basically can be interpreted as an “efficiency” multiplier.

Expansion

In Diner Dash, profit is proportional to difficulty. This is enforced in each level as a cash requirement which must be met to advance to the next stage (otherwise the player must retry). Therefore as profit increases and the players advance to higher stages, the profit is used to buy new nicknaks for the restaurant. Each of these items adds a new wrinkle of variation and difficulty to the game. For example:

podium

- Flo can stand at the podium and talk to qued customers to refill their hearts. The podium becomes a crutch to manage the flow of customers and boost the satisfaction of waiting customers. It makes sense to retreat to the podium when the seated customers are eating or the food is being cooked.

larger tables or long counters

- Different sized tables give the player new constraints to work and strategise within.

snack station

- Snacks can be used to please dissatisfied customers or, as becomes frustratingly frequent later in the game, customers will request snacks, in effect snacks act as combo interupts as dishing out snacks will create a new combo.

drink station

- Same as snacks.

Playing to Win

The goal of each level is to meet the requisite dollar value to progress to the next stage. In this case, exploiting the most out of the abstract systems is critical to success. As mentioned, there are 3 ways that the player can make more money: more customer satisfaction (hearts), colour matching customers and chairs, and the action chain bonus system, so doing the same $ task in succession.

Of all three methods the action chain bonus system is the most effective. Refer back to either one of the 2 screenshots above and count the number of tables. 7 tables. Consider this, each time you take an order you gain $20 and the multiplier increases by one value. So, taking the orders for 7 tables will net you $1280. Now, when you deliver the food the player gets $30 a table, $50 for taking the cash and $40 for taking the dishes. Add up all of those possibilities and it’s easy to see how the action chain bonus rakes in the dough.

As for the other 2 methods. The hearts only determine the tip at the end which may be around $100 per customer, so really, looking after the customer’s level of satisfaction isn’t so important. The customer’s favourite colour also doesn’t mean a great deal as colour matching is tricky and time consuming, an overall hindrance to the action chain bonus.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bi12cvrIKygThe action chain bonus is a system, which earns the player the most amount of money, is best exploited by the player lining up groups of customer sets and repeating the same $ action. Diner Dash supports the player maxing out this technique by continually adding tables to each level, allowing for bigger lines of actions to chain. The video above is a nice demonstration.

To make Diner Dash more challenging, the snack and drink stations are used to break the players combos. It’s not the stations themselves that break combos, but the customers that request food and drink from them. As you plant customers in their seats and run through the various states, lining up repeatable $ tasks and all that, some customers will request a snack or drink and change their state to a “request food/drink” state. Giving the customers the snacks and drinks they request will start another chain combo and cancel the current one. Since it’s random whether or not the customers will request a snack, drink or simply not request at all, and the window open to meeting these requests is quite narrow, these devices are an unstable way of building combos. Food and drink requests are effectively a way to hinder the player from building up more chains. This is why I’ve dubbed these extra requests as “interupts” (refer to video for examples).

At this point the player has 2 options: give the customers the drink or snack that they are requesting or wait until the customer becomes impatient, loses a heart of satisfaction and reverts back to their prior state, continuing as before. Of course, smart players know that the heart-dependent tip at the end counts for very little, making it an easy sacrifice in the face of the action chain bonus. In fact, by the time Flo becomes a mystical 4-handed God in the final restaurant, the number of chains amounts to such a rich profit that even customer walkouts aren’t a huge deal. Of course, they should be avoided, but if it happens, it’s only a $1000 loss in the face of chains of $1000+ being made every 20 seconds.

Through all the money making, a clear strategy emerges (refer to video if needed):

- Stand at the podium until all customers are maxed out with hearts

- Place customers in their seats

- Go back to the podium to keep waiting customers maxed out and wait until all seated customers are ready to order and most of the snack/drink requests have or, by the time you get the customer, will have expired

- Take orders

- Take the orders to the ticker

- By the time you’ve dropped the last few orders, the first dishes will be ready, send them out

- As seated customers eat, head back to the podium and amuse the waiting customers

- Again, ignore all requests for snacks and drinks, unless customers are threatening to storm out

- Take money, can head back to podium and wait for slow eaters

- Take the rest of the money

- Clear dishes

Interactive Capitalism

Watch from 5:10

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zchsu7emVEsSo what does all this have to do with capitalism and the food industry? Watch the video above and see if you can catch the connection.

“They trained each worker to do one thing again, again and again.”

Diner Dash is an interactive model of the modern food system in restaurants as it privileges repetitive actions within a restaurant context. Flo’s diner is a one-man factory. There is one single most effective strategy to run the factory and that creates a uniform style of play. Flo’s wealth only increases more and more until the game must create a faux ending where Flo becomes a 4-handed God. In one sense, Diner Dash could be rebranded and tweaked to become McDonalds: The Game.

Despite this connection, you may be wondering what the factory model of cooking has to do with capitalism? Well, the factory model of food production and delivery is the cheapest means of production. Cheapening production is the easiest and most typical way to fulfil the profit motive: the core tenet of capitalism. Therefore, Diner Dash uses a capitalist model of food production and Flo/the player is the agency that sets the system in motion. My argument is based on 2 facts that have been established so far:

- The player’s motivation and the motivation behind capitalism are the same: profit. If the player can’t gain more profit, the game goes nowhere. If corporations don’t keep earning more and more profit, the free market dies.

- The best way to meet profit expectations is to rely on a safe, mechanised means of production. For contemporary capitalism, this means is the factory. In factories workers repeat a given set of actions over and over, as does the Flo/the player in the game. Both capitalism and Diner Dash are factory systems.

A few points of clarification are needed though. By production, I mean the entire process up to the point of consumption as the delivery itself is part of the production process. While this may seem dubious to my argument, it’s really only a matter of context and no matter what context, the rules of Diner Dash and the rules of capitalism are still analogous. (This is, like most of the writing here, a discussion of the underlying rule systems). But if you still need further proof, why not take the switch out my analysis of Diner Dash for the Cooking Dash variant. Both games have the same core systems, but the latter is better suited to the appearances of the analogy. Let’s carry on…

(Cooking Dash)

Since Diner Dash and capitalism share many properties, arguments for and against capitalism can be made through Diner Dash.

Pro-capitalism Arguments

In the same way the player comes to master the strategy that I dot-pointed earlier and aggressively stick to it, people in business have such an endearing dogma towards this property of the free market. Once either player (gamer or businessman) realises that this strategy of factory-style labour is the most effective for winning (the game or the market), then there is little reason to change.

In Diner Dash, uniformity of production is privileged through the action chain bonus system, as is the case in capitalism and standardisation of product.

Capitalism is based around the profit motive in the same way Diner Dash is based around the score motive.

Diner Dash is a game about expansion (see expansion heading above) just like capitalism is a model of continual progression. Where capitalism seeks to advance new technologies for the sake of even cheaper production (in allegiance to the profit motive), Diner Dash expands the set of items in the restaurant and arguably the depth of the gameplay.

Just like other games which model capitalism (GTA and Osmos, for example), the game ends when a peak is reached.

Anti-capitalism Arguments

Flo may be making a great deal of profit, but by way of turning herself into a robot. There are people that have to work in these factories and humanity isn’t something that melds too well with the profit motive. The irony being that Diner Dash is fundamentally the same as work, except that because the player draws enjoyment from being in a position of “control”.

Diner Dash is a little unique here in that the worker of the restaurant is also the boss. Despite this, Diner Dash still presents a workers vs profit motive argument which can be interpreted as waitress Flo vs Flo the boss.

Capitalism is successful often to the exploitation of resource which includes people’s quality of life and the environment. Diner Dash presents this in 3 ways:

- the mechanisation of Flo’s working life

- the lack of space in the gameplay for the player to seat the customers in their favourite coloured chairs (read: the game disallowing the player from easily making the customers happy)

- the player having to discredit the happiness of others to meet the profit motive (action chain bonus, snack and drink interrupts). Even if this means customers will walk out angry.

Marxist critique of capitalism says that capitalism will end either by a workers revolution or a complete and utter breakdown of the system. Before the system breaks down altogether though, there will be a series of minor collapses (think strokes), before the system fails altogether. Critics of capitalism believe that the world financial crisis was such an example and that, as according to Marx, the solution to the problem will only be a band-aid one. For example: the conservatives in the UK cutting public expenditure, raising university fees and blaming the populace for being so greedy. America’s bail out plan of giving money back to the banks and fat cats as another example. Capitalism cannot be restrained or regulated, it can only be removed.

We see this exact problem in Diner Dash‘s design. The only way for Diner Dash to increase difficulty is to lump more things at the player’s task list. This works okay for a while, before the design becomes cluttered (again, this video, now imagine it on a small iPod screen!), making Diner Dash too difficult to visibly determine core elements, too tricky to tap them and slows down the speed of the device dramatically. Like capitalism, Diner Dash responds with a band aid solution: give Flo 4 arms! This solution is obviously quite ridiculous, but it works for a few levels until, say maybe the final level, where Flo’s use of the chain system in conjunction with her new arms gives her an enormous advantage and the profit level is off the charts. For example, I scored $69,855 in the final level, nearly 2.5 times the goal of $26,000 and a tad shy of double the expert score of $35,000. You’d think that the only way to fix this would be to add more tables and interupts, but this would only further clutter gameplay. The difficulty goes totally out of whack (in the same way the multinational corporations are making unbelievable profit) and the only way to repair the game (or capitalism) to remove it and start again.

Conclusion

I’ll admit that as a socialist it’s difficult for me to say anything nice about capitalism, so even my pro-capitalist arguments are thinly-disguised criticisms, but regardless of that, we can see how through the player’s motivation to reach a dollar score to advance and through the way repeated actions are privileged, Diner Dash’s gameplay system is analogous to capitalism. From this, we can use Diner Dash as a means to talk politically. Furthermore, even without the player having any sense of it, they are participating in this system of economics and subconsciously interpreting it. Video games, like economic systems, are simply that, systems. Akin to the same link between video games and education or the rules of nature, gameplay can act as a window for us to further our understanding of the underlying systems around us.

God of War III – Graphical Attrition

December 17th, 2010

A few hours into God of War III, after the thrill of lustrous graphics wears off and the quota of mega set-pieces is spent up, it becomes widely apparent that replaying the original God of War for the third time over isn’t all that fun anymore. Following the tremendous height of the opening sequence ascending Mount Olympus on Gaia’s back (however contrived it may be), God of War III‘s new ideas and samples of sharp design are few and far between, and in conjunction with the facade of epicness the visual purpose, I found it difficult not to feel anything but pure deceit.

Never Judge a Book by its Cover

Graphical fidelity, being part of the context, what the player actually sees and therefore interprets the game to be, asserts a great deal. To us visual creatures, a high-end visual presentation suggests premier quality and importance, while a low end production suggests modesty, simplicity, cheap or poor quality and/or niche appeal. This appraisal is obviously a false one, but it’s a natural one as well, one that we can’t really avoid. As much as I trumpet on about rule systems and whatnot, it stands that when I see a game like God of War III, the visual presentation has an effect, a psychological effect denoting importance.

Disconnect between the presentation and the reality of the gameplay (rule systems, mechanics) can therefore be dangerous for a high production title and, on the other hand, a non-issue for a low production title. When a God of War III show-ponies high technical prowess and then fails to match this level of excellence in regards to game design, players get suspicious. (Such is the case with the contrived battles against the titans). And players ought to be suspicious since, due to the psychological component of appearances, they’re effectively being fooled into thinking that something is greater than it realistically is. At some stage there has to be a realisation.

The realisation creeps up on as with our ever-shifting interpretation of the visuals. As we familiarise ourselves with the visual construction of a game, the original impact and magnitude that the presentation had on us loses out to a more functional interpretation. Bumps in our conciousness for aesthetics occur when the game sparks our interest again with new environments, characters and effects. While game designers are getting better at engineering these types of bumps, along with other poor design tricks to keep players going, there will inevitably be a realisation point. And once the player arrives at that point, their enthusiasm sours.

Personal

In my eyes, God of War III failed to maintain visual interest through its mid-section of similarly-looking Greek-inspired architecture and underground labyrinths, as opposed to God of War II which traveled through snow, forrest and sky. Most importantly, however, is the fact that the game was getting continually less interesting the more you played it. That is, in addition to a sheer drop in pacing, the past 4 articles of criticism began bubbling to the surface in my subconcious.

Hollywood is Dead

For me, God of War III drilled the “graphics are ultimately superfluous” argument into the forefront of my brain and has completely turned me off of what Microsoft and Sony are marketing as “hardcore” experiences. These companies are training us to buy the virtues of hollywood and not the virtues of good design. Not that the two are mutually exclusive mind you, but rather one set of priorities can come at the detriment of the other. An industry that has mindless expectations for these supposedly Titanic sinking experiences wrapped up in digital glitter is not an industry that I want to support.

And so there is probably a point of contrast, a game that stands in humble opposition to these free-roaming Goliaths—and that game is CrossworDS (also known as Nintendo Presents: Crosswords Collection in Europe). Here is a game free of glamour and pretension, and faultless in its design.

I’ve been playing CrossworDS regularly for 6 months now and have got a great deal of enjoyment out of it over such a long duration. Here is a title which is humble, unassuming and delivers precisely on what it set out to do. Furthermore, CrossworDS has enriched my life and the lives of people around me. CrossworDS has:

- given me much enjoyment and satisfaction over a long period of time

- improved my ability as a wordsmith

- been the last game since Doctor Mario that my own Mum (whom never plays games) will ask me to set up so that she can play for hours at a time

- been a wonderful tool at helping my Chinese girlfriend practice English and a great 2 player game that we can play together

God of War III aims at an insurmountable high point, fails epically and leaves the player ultimately feeling hollow and malnourished. I’m not just singling God of War III out though, other PS3 games of a similar vein have left me feeling the same way. These games are like fast food for the soul, getting worse as they try to be all the more gigantic. In which case, God of War III is the last bout of food poisoning I’m willing to stomach. Good design and humility all the way!

God of War III – Kratos: Villain, Anti-Hero or Indifferent

December 14th, 2010

Many times during God of War III I felt that the game was trying to make commentary on Kratos’ role, not as an anti-hero but as an actual villain and eventual redeemer. Although it’s obviously intended that Kratos looks and acts like a complete bad ass, God of War III occasionally oversteps this mark, portraying him as a cold-blooded killer. The game’s villains (various gods), through their dialogue, all explicitly state that Kratos has stepped even outside of his own bounds and become consumed by his own revenge.

The God of War series is about the spectacle, not about the politics so this commentary puzzles me. The objective lens is turned on far too frequently in God of War III to be considered unintentional, yet come the end of the game, the conclusion regarding this critique is unclear, giving me the impression that the objectification is perhaps misplaced or under-realised. I’m left thinking that Sony Santa Monica tried to be serious about its protagonist in the same way it tried to create a meaningful ending, and as we know from the last post, the ending was a complete train wreck.

In any case there is a thread to follow on how Kratos is portrayed as a villainous murderer consumed by his own revenge. Let’s follow this thread and see how it establishes Kratos’ role throughout the game.

“The measure of a man is what he does with power”

The above quote kicks off God of War III, giving the player something to ponder and ponder I did. If “The measure of a man is what he does with power” and Kratos’ power can be interpreted as his sheer strength then clearly his slaughter of those around him defines him as a villain, if nothing else. Maybe this quote at the start of the game is a little preempt given that we haven’t seen what Kratos does with his power yet or maybe its trying to set a precedence.

A Bloodied Hero

The technology of the PS3 allows Kratos’ body to become stained with blood as he tears through his enemies. This touch of realism quite literally paints Kratos as a more brutal character. Furthermore, aside from the blood washing away in water, the player can’t respond to the blood and neither Kratos in the cutscenes. Therefore, through the player’s inaction Kratos accepts such barbarism as normality.

Poseidon POV

Watch this video from 2:50

I would argue that the point of view in the cinematic here (the first battle in the game) has a stronger impact than any of the other prior God of War cutscenes entirely. The series has always been brutal, but Kratos’ meeting with Poseidon, as viewed in first person through the eyes of the victim, indiscriminately frames Kratos as a bully, murderous, bordering on cruel and barbaric.

Change in Tone

If you watch through to the end of the above video, you’ll notice another change in Kratos’ character: his tone of voice. God of War III‘s story is re-aligned to suit mood of the original God of War instead of its boisterous sequel and, as such, Kratos speaks softly at times, presenting him as a more rational character. The narrative also returns to the topic of Kratos’ origins and the death of his family. These sequences which attempt to rationalise Kratos’ quest for revenge seemingly falter with the high contrast of Kratos’ personality when beating the gods into submission. For example, the fact that Kratos doesn’t just kill Poseidon in one go, that he tosses him around and lets him scramble while walking slowly up to Poseidon ignoring his pain and pleading all put forward the impression that Kratos wants to cook him slowly. It’s hard then to see his brutality as justified simply because of his prior circumstances.

The confrontations with the other gods are similarly cruel. In the battle against Hermes for instance, Kratos chops off one of his legs and then, in the player’s control, Kratos can only walk slowly towards Hermes as he backs away with one leg in agony.

But then that seems to be the point of God of War III, to paint Kratos as a man which has pushed himself past all reason, consumed by his revenge. As the narrative continues it only pushes us further towards this idea.

Gods Dialogue

Zeus plants this supposition early on when he states (first video above):

“Athena is dead because of the rage that consumes you Kratos. What more will you destroy?”

Every other god in the game invariably echoes the same sentiments. This affirms the interpretation that God of War III is portraying Kratos as a man consumed by his own revenge.

Saving the World

In this cutscene too, we see Kratos’ clear ignorance of everything around him bar his revenge for Zeus:

Athena: “As we speak, the war of Olympus rages on and mankind suffers”

Kratos: “Let them suffer, the death of Zeus is all that matters.”

On the other hand, Athena also convinces Kratos that “as long as Zeus reigns, there is no hope for mankind”.

This cutscene sends mixed messages to the player. It says that Kratos doesn’t care for mankind and is letting it suffer, yet is perhaps, at the same time, letting it suffer now knowing within himself that he will enact his revenge and, as a consequence, there will be “hope” for mankind. This “hope” that Athena speaks of is vague but becomes important later.

It’s hard to tell what Kratos is thinking as most cutscenes are opaque when they delve into Kratos’ thoughts beyond Zeus. Here is an excellent example of how Kratos avoids any form of expression:

When Hera confronts Kratos and questions him on the problems he is causing, Kratos doesn’t make a single utterance, making it difficult to construe his thoughts. We have to therefore understand him through his actions and at this stage he appears to be disinterested in anything aside from his revenge plot.

Killing the World, Saving it, or Neither

As Kratos destroys the gods, each death affects the earth in some way. This can be seen in gameplay.

- Poseidon – Water levels rise

- Hades – Hell’s souls are released

- Helios – Sun is gone and storm rage the earth

- Hermes – Plague is unleashed on the world

- Hera – All plant life dies

Kratos Kills All Allies

Kratos kills bothe of his major allies throughout the game: the titan Gaia and Hephaestus. Gaia is killed because she abandons Kratos, leaving him to again confront Hades in the underworld and then demands that he stops intervening in a matter for the titans. Gaia herself wishes to kill Zeus on behalf of the titans and because Kratos is only interested in taking the honours, Gaia is removed. Of course, she is brought back to life, climbs Mount Olympus and is killed again. Hephaestus is killed in self-defence.

What we can gather from these 2 characters is that if they aren’t willing to aid Kratos, then Kratos will forcibly remove them for good. Continuing the theme of “barbaric man consumed by revenge”.

Gaia is also a reflection of Kratos’ dogmatism in being the first and only person to kill Zeus. The death of Zeus is not suffice, Kratos must do it personally. Hephaestus shows a Kratos’ lack of remorse towards such a pitiable character.

Pandora’s Box and Retconning

Athena reveals to Kratos that Zeus can only be destroyed by acquiring the power to kill a god found in Pandora’s box. Of course, Kratos already used this power in God of War to defeat the final boss Ares, but supposedly there’s more pixie dust inside; he just has to open the box again and find it. And so starts a convoluted story retcon which requires the player to be hit over the head with exposition (ala more talky cutscenes) just to get the general point across.

In short: after the great war, Zeus commissioned the blacksmith Hephaestus to create a box to store the evils of the world (hate, greed and fear)–and Athena slipped in hope without Zeus knowing (secret plot twist!). When Kratos opened the box in God of War, he unleashed the fear which ultimately created the conflict between Kratos and Zeus.

Fortunately, the core family of titans, gods and other characters are all mixed into the retcon. For most, the fear in Zeus has wrecked there lives and left them pissed off with Kratos (Chronos, Hephaestus, all the bosses) for opening the box. Kratos is pretty unremorseful to these people, which helps create situations of conflict to further exacerbate Kratos role as chief bad dude. (I know that I’d be annoyed if someone pulled this trick on me and then everyone else hated on me for it).

While the story as it leads into the second half of the game becomes continually more tangled in this nonsense, at least the retconning brings Pandora into the equation and henceforth we can continue to follow this thread.

Pandora

Pandora is the last key part of Kratos’ good/bad guy characterisation before we see whether or not this villain can be redeemed or, alas, save himself from his own rage. Pandora’s role is as an overworked metaphor for Kratos’ daughter. Naturally, Kratos has some affection for the freckly-faced teen, but it takes a while for it to sink into Kratos’ head (and even then we don’t know if he really cares). This is surprising given her unabashedly direct saturday morning cartoon dialogue. See lines like:

“Hope is what makes us strong. It is why we are here. It is what we fight with when all else is lost.”

I think that Kratos ultimately does care for her as he refuses to sacrifice her to the flame as seen in this sequence:

One could also infer that Kratos treats Pandora well because of some possible remorse for Hephaestus or just for the purpose of defeating Zeus, but it’s clear that his refusal to sacrifice Pandora contradicts the latter.

Again, the gods dig to the heart of the matter:

Zeus: “Don’t confuse this object, this construction of Hephaestus with your own flesh and blood.”

Kratos: “This has nothing to do with her”

Zeus: “It has everything to do with her”

First (and only) Sign of Change

The very first time Kratos responds to the assertions made about him throughout the game (and the ideas we’ve been following up until now) is right at the end. Athena demands that Kratos hand over what was in Pandora’s box, but as Kratos states, the box was empty. It seems that Athena is after the “hope” that was either in the box or somehow passed over to Kratos through Pandora (it’s never made clear). Kratos must know that he has this “hope” because his hands and eyes are the colour of Pandora’s spirit, blue. Again, maybe he doesn’t; the game is vague.

In this final scene, Kratos looks over the world from Mount Olympus and possibly takes the moment to consider the consequences of his all-consuming vengeance. Then, in his last act he says to Athena that Pandora died “because of my need for vengeance” and then states that he will put an end to his vengeance and kills himself. Kratos could not die prior to the existence of the gods (as we find out at the very end of the original game), so now he seizes the opportunity.

Kratos’ epiphany is short lived before he takes the easy way out and sacrifices his life. So has he really learned anything? On the other hand, despite finding the hope in his own near-death subconscious and everything Pandora has said to Kratos, he still kills Zeus. The world is destroyed, Athena was shafted, the gods are dead and there’s blue sparkles all over the place. The player, who by this stage has been side-lined to a viewer, doesn’t know:

- if the world is saved (by Kratos apparenty unleashing his “hope” on the world) or doomed

- how exactly Kratos came back to life

- why he killed Zeus after seemingly being endowed with “hope”

- if Kratos’ suicide is a brave or weak act

- has Kratos found his peace

- what does Kratos’ suicide and the blue sparkles of “hope” mean

- whether he was planning on killing himself to begin with

- does the blood trail at the end equate to more franchise milking?

In the end, has Kratos learnt anything? Was there really any rational point in the destruction of the planet just because Kratos was angry? The ending is vague on answers, probably because it lost so much direction by basing the plot around a retcon and then introducing a major new character for the second half of the tale.

Conclusion

Kratos’ exit from the game without any explicit response to the commentary the game shares ultimately renders the commentary itself as ineffective or Kratos as having learnt nothing. There is no closure on the story. All we know is that Kratos was obviously driven by hate and because of it the world is in ruin. Nothing was learnt or gained. What an unfulfilling story.

Pinpointing the problems with God of War III‘s narrative has been a lesson in frustration and some of that frustration has affected the writing. If you got more from this article than God of War III‘s narrative, then consider my mission complete.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99