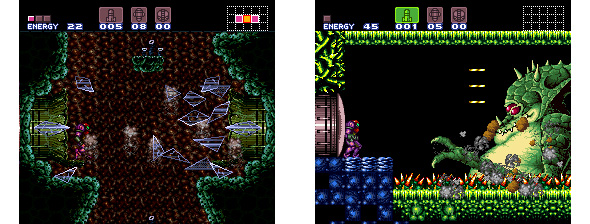

Super Metroid – The Mental Map

August 16th, 2010

Game designers create rules, a system of challenges and a gateway into that challenge (tutorial). Players, through their participation of the game world, mutually agree on the terms set by the designers. Therefore, there is something of a student and mentor relationship at work between player and designer. (Mr. Miyamoto recently commented on this phenomena a little himself). The foundation of this relationship is that of the relevant skills required to defeat the game: the teacher wishes to teach these skills, the student wishes to learn them. In which case Metroid is a test in observation and a test in the application of tools (power-ups).

Metroid‘s challenges, its tests, if you will, are built into its environment in the form of realizing suspicious chunks of area and then devising a way on how to clear that area to make progress to the next planetary subsection. Sometimes you’ll have the means to make headway, and other times you’ll need to mentally bookmark or flag down the spot to return afterwards. On a wider level though, Metroid, keeping in fashion with its exploration roots, also challenges the player in a third test of skill: the skill of mapping out one’s exploration.

In terms of what the player is constructing in their head, Metroid is an array of these “hotspots” (suspicious rooms which may be mined for progress) linked together into coherent routes and mapped around save stations. These mental pathways are connected through distinct visual markers which define particular chunks of environment from one another. When we play a Metroid game, we visualize these mental maps, with support from the in-game map itself (of which doesn’t contain the information gathered from exploration), and, in accordance to this mental map, we pursue the next string of clues.

Not only do we visualize these routes, often with aid from the map, but said routes are cross-checked against our current ability set as to whether they are viable or not to the area in question. Sometimes these clues lead us to undiscovered areas, sometimes these clues lead us to areas we’ve previously visited.

Most vividly we are concious of this play pattern right after we load the game up and begin at the last save point. It’s here that we gather our strategies and formulate a course of action, so at this point, the mental map is most relevant.

Keeping the Squeeze

Super Metroid, above all other games in the series, facilitates exploration management fantastically. The two most obvious reasons for this are the inclusion of an in-game map and the improved graphical capabilities over the original Metroid.

The in-game map works as a crutch for players to refresh their own mental map. Wisely, R&D1 chose to segment the main map away from the core gameplay by virtue of the pause screen, only offering a mini-map of surrounding rooms while the player navigates Samus. In this way, where pausing to check the map disrupts the flow of gameplay, players are persuaded into relying upon their established mental map.

With the added power of the SNES, environments – i.e. the visual markers which we use to identify and compress the landscape – are capable of being more distinct, hence making it easier for players to crystallize visual markers into their memory.

“Dead ends” – pathways that the player would preempetively follow before they receive the respective power upgrade necessary to progress in said area – from the original Metroid, now offer up minor weapon upgrades in Super Metroid, thereby decreasing player pitfalls and frustration while at the same time rewarding early curiosity.

Super Metroid is also a far more smartly segregated title than the original Metroid. The environments, while equally as large as the original Metroid, are focused into shorter, more succinct instances of play. Save points quarantine these instances of play that can later be mined for leads which allows for some dynamic threading of routes. Hub rooms, often near the entrance to a new area, take on a more skeletal structure with the purpose of each pathway conveyed more promptly. That is:

- some areas are hard blocked with sealed doors, indicating a long delay before the player revisits with new power-ups;

- some areas which require a currently-unavailable-but-soon-to-be-acquired power-up are softly marked, promptly too, as in the first room or so. Examples of these soft markers used to detract the player are a sudden absence of background music, flora and fauna met with apparent markers of essential-but-still-not-acquired weaponry (boost tracks, swinging junctions). These indicators, used to steer the player back on course, are made apparent in the first room or so (Metroid would often lead players down long corridors before confirming to players that they’re presence in the area was not currently required); and

- areas that the designers wish the player to advance through are often backed up by the respective sub-terrain theme music, denser wildlife population and a more visually “alive” environment.

The fascinating thing about Super Metroid is how the maps begin by following this skeletal structure and then, as the player subsequently revists one area multiple times over, hidden divergences bleed into the map structure (ingeniously represented by a different colour on the pause-screen map). The maps therefore begin in cocoon-like states, allowing the player to build a foundation of the environment, then, once their mental map consolidates, the pathways blossom into one another as reliance on the in-game map fades.

With the bleeding of the map, cleaner visual markers, fewer dead ends, a more logical and directed conveyance of purpose within the environments, Super Metroid constantly feeds the player’s mental map and thereby continuously drills the emergent skill of exploration management.

Wario Land 4 – Design Discourses

August 12th, 2010

Games with good game design are those where all components of the game are grounded to a core philosophy or set of philosophies. The world of Mario is tied to jumping, the world of Metroid is tied to exploration, and in the case of the Wario Land series, Wario Land is tied to Wario’s wacky persona. Underpinning the philosophy of form meets function, Wario’s outwardly fat, greedy and cartoonishly sinister appearance are a reflection of his abilities and the interactions made possible within the game world. Let’s use Wario Land 4 as an example to briefly observe the way Wario’s character reflected by his interaction and abilities.

Weight

Wario’s array of moves are all tied to utilising his best asset, his visibly bulging weight and super strength. Just like the stylised visual appearance of the character, Wario’s strength and weight are exaggerated through his interaction. No ordinary obese man could crush through rock, create minor earthquakes, flatten small minibeasts or turn into a menacing snowball by building momentum off diagonal slopes, however, Wario can.

Aggression and Greed

Wario’s is presented as an aggressive character. In the game the player is persuaded to be aggressive, meeting the Wario persona, through the rewards of coinage which liberally flows from downed foes. The more aggression you show, such as by throwing one enemy at another, the more the player is rewarded. Unlike in prior Wario games, Wario has a health bar this time, so coins are no longer a currency for life. That is, they are no longer handicapped but instead free-flowing. As we can see, on element of Wario’s behaviour (aggression) acts as a means to highlight another (greed).

Self-deprecation

The folded levels of Wario Land 4 that require the player to reach an endpoint and then, pressed by a time limit, run back to the start of the level make fun of the stout fella’s inability to make haste under pressure. This, I’d argue, works to justify the cartoonish nature of the game through self-deprecation. Perhaps a more obvious example is the way Wario shape-shifts into various different forms. Each one seemingly poking fun of Wario as he is stung by a bee, turned into a zombie, set on fire or flattened into a pancake. Every transformation is met with an “oh no!” cry as though Wario wishes to avoid the humiliation.

Conclusion

As we can see, the way Wario can interact, and the way the player is taught to behave are all representations of Wario’s anti-hero persona. These interactive elements don’t just support the visual image of Wario, but are in fact pivotal in defining his character. It’s no wonder then that players of Wario Land 4 and the other Wario games, have such a vivid understanding of the character himself.

God of War II – A Review

August 12th, 2010

Three months ago, and with grand foresight, I vowed to consume as much media (games, movies, comics, books) as I possibly could before I’d leave almost all of it behind as I go to live abroad in China. Some of this media I managed to write about before I left, some of it I’ve subsequently caught up on over the past three months, and then there’s all that note-taking sitting in OpenOffice documents in my writing folder. God of War II belongs to the latter.

God of War II is a direct narrative and gameplay continuation of God of War, which means that, similarly to the Half-life episodes, God of War II streamlines the culmination of mechanics built up by the conclusion of God of War and re-uses them as a base for the beginning of God of War II. By virtue of being welcoming to new players though, Kratos is robbed of these abilities by his father-cum-uber-nemesis Zeus at the game’s onset, acting as a narrative justification to re-teach the ropes and warm players into the experience*.

For continuing players this amounts to a heap redux which God of War II‘s largely peripheral additions to the combat system fail to quell. (Newer players will similarly find the combat stretches beyond its means, but perhaps not as immediately as returning players). A smattering of aggressive new moves mapped to the L1 button when used in conjunction with the face buttons, a spiffied up Rage of the Titans (rage mode) and some new spells do fend off the familiar, but fail to sustain player interest through what is a significantly extended play experience.

That’s not to discount the peripheral additions though, since, as irrelevant as they are to the most established part of the experience (the combat), they do in fact play a part in pushing the game forward. Kratos has a couple of new weapons at his disposal, including a hammer, sword and bow. Aside from the arrow which can be rapidly shot between intermissions of slashing to maintain combos, none of these diversions are given enough spotlight to deliver attention away from the effectiveness of the Blades of Chaos. Smart players will realise that the best way to play God of War II is to ignore these distractions and rely on the tried and trusted attack patterns from God of War while adding a bit of oomph, now and then, with the new L1 attacks or the spells.

It’s a shame that there isn’t enough added variance to the combat as God of War II is an excellent example of good organisation of gameplay elements. God of War II shifts from combat, to puzzling, to platforming, to narrative, to boss battle with an exacting sense of understanding of how much can be bitten off of each of these systems. Furthermore, new mechanics, landscapes and enemy types are interspersed at the most suitable points in the game. You are always presented with something new and interesting just as your enthusiasm for your current occupation begins to wane. Sony Santa Monica clearly nailed this element with a hefty amount player testing, which is why it’s disappointing then that the depleted combat systems works only to subvert the games otherwise great pacing.

It would be remiss of me to forget God of War II‘s stronger emphasis on puzzles, platforming and set pieces, all of which have been well supported by the new time freezing, flying (Icarus’ wings), chain swinging and Medusa’s head mechanics. The set pieces, particularly the flying sequences, are always exciting and well connected to the context of the game (for example, obtaining Icarus’ wings). The boss battles are equally impressive in the way they draw on more elaborate forms of tactics and spatial awareness which isn’t encountered in the moment-to-moment combat.

But ultimately, none of this can save Kratos from that niggling itch that the combat is not fresh and exciting enough to sustain the experience. The end result, which is overbearingly evident by the end of the game, are the large slumps of uninteresting gameplay which undermine the entire production. By failing to directly address the heart of the experience (the combat) in a meaningful way, I don’t think that God of War II is deserving of its title as the “magnum opus” of the PS2. In saying that though, the combat still holds a level of succulence which cannot be denied and despite the lack of revision, God of War II is still a premier action game, particularly in light of the excellent pacing of the experience.

*This last point is surprising given that God of War III simply dumps immediate tutorial on the player.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99