Enjoyable for all Audiences: Klonoa and House of the Dead: Overkill

April 29th, 2010

This is something of a special take on my regular ‘Play Impressions‘ feature. Klonoa and House of the Dead: Overkill, despite their differences in content, are great examples of games which channel the ethos that the Wii was founded on: accessible gameplay that breaks down the barriers between beginner and seasoned players. Both of these titles are of genres of relatively low complexity which further adds to their expansive appeal. I will focus on how their designs are logical to players and ultimately very successful games.

Klonoa

Klonoa is a remake of the 2.5D PSone platformer Klonoa: Door to Phantomile for Wii. The platforming borrows mechanics from Yoshi’s Island and Wario Land, but alters and combines them in a refreshing way. Like Yoshi, Klonoa has a flutter move where he can temporarily keep himself afloat in mid-air and like Wario, Klonoa can pick up enemies and launch off them to gain extra height. When these mechanics are combined in succession, Klonoa comes into its own, offering an emergent technique for more capable players which allows Klonoa to travel great horizontal and vertical distances without touching the ground.

Klonoa can also toss enemies in front of him or at objects in the back and fore grounds, allowing for some nifty puzzles. In fact, I’ve never played a game which has so dynamically implemented 3D environments on a 2D plane. It’s all quite impressive the way paths spiral around and Klonoa shifts to layers which were previously a part of the back/fore ground. As with the combination of jumping mechanics, it’s when the backgrounds and foregrounds interconnect and loop around to create multilayered puzzles where Klonoa excels.

It’s the bridging of separate, easy-to-understand constituents which make Klonoa a joy to play for experienced and inexperienced players. In fact, Klonoa is an ideal game for children; I would have loved to play his game growing up. The story in particular deserves special mention in this regard. Unlike Jak and Daxter or Rachet and Clank who play on youthful, adventure-seeking archetypes, Klonoa and his blue-ball sidekick Huepo are adventurous but reserved, displaying a natural pure-heartedness rarely seen in video games. The sense of friendship shared between the two is heartfelt and the conclusion to their tale is one of the most touching I’ve experienced a video game—less we forget this is a production made for children. Playing Klonoa had reminded me of the importance of developing games for a young audience. However, even if you’ve long since past primary school, as a fan of 2D platformers, I can’t recommend this under-appreciated gem enough. The best platformer on the Wii bar Mario.

House of the Dead: Overkill

There is surprisingly very little to say about House of the Head: Overkill from a mechanical standpoint. As I mentioned in my rail shooter guide on Racketboy, Overkill employs a simple combo system where flawless, no-miss kills tally a tiered combo system with each multiplier assigned to over-the-top names like like ‘psychotic’ and ‘goregasm’. Shots are divided into head shots and body shots.

Players can now choose a two weapon loadout prior to each mission, supported by a shop system where players can tweak and add weapons to their arsenal. In many respects, the two weapon loadout—arguably the only “new” addition to this installment, if you’re into series progression and all—injects a strategic dynamic into the core gameplay since players can switch weapons to conserve ammo or for tactical efficiency. There’s a degree of strategy in pairing up clunky, rapid-fire or standard weapons depending on your strengths. It quickly becomes apparent though that the shotgun, with its wider target area—as represented by the large reticle—awesome power and lack of ineffectiveness when shot into the distance, is the most efficient weapon for high score chasing, and once you’ve maxed it out, you’ll almost never use the other weapons. Personally, I’m hardly a high score chaser, but the scoring system in Overkill, due to it’s simplicity and prevelance in the UI, is more apparent than in prior games, which piqued my interest. High scores are rewarded with cash, so it all ties back to the upgrades system which is scrimpy at best, ensuring that you’ll need to play every level at least 3 times before you earn enough dough to max out all the weapons.

The player also has a substantial health bar which on depletion offers the option of sacrificing half your score to continue. Branching paths have been removed entirely which give more focus to the narrative—and with plenty of health packs, slow motion prompts, grenades and ‘save the civilian’ moments, Overkill is quick to orientate the players concentration towards accurate shooting and the rewards subsequently accumulated from the combo system. The novel grindhouse presentation may appear to distract from possible lacking amenities, but this couldn’t be further from the truth. All components of House of the Dead: Overkill: the linear progression, health bar, cash system, in-game trinkets, UI, all work to consolidate accurate shooting: the game’s core gameplay premise. In addition to the excellent production values and comedy-driven narrative (the latter of which, I think anyone could enjoy), Overkill, just like Klonoa, is a fantastic game for both seasoned and new players alike. I think that it’d also be a good introductory game for players wanting to further explore the rail shooter genre as it focuses so heavily on accurate shooting: an integral skill required in these games.

Overkill also provides incentive for players to keep working on their accuracy with a standard story mode, the option to add more mutants and a final “director’s cut” version which adds a significant amount of content per level. The final pay off is the ability to dual wield with too Wiimotes which is a rather handsome reward. Again, this plugs into the accuracy element of the game.

Additional Readings

The Making of the House of the Dead – British Gaming

Play Impressions (14/4/10)

April 14th, 2010

Meteos

Meteos is a neat match-three puzzle game for the DS which involves dragging blocks vertically to match with same coloured blocks, either horizontally or vertically, which sends them flying past the top of the screen to a neighbouring planet. A stream of blocks continuously rain over you (hence the name Meteos, ie meteors) until you’ve lodged enough blocks into outter space to blow up the respective planet. There’s a bizarro narrative linking all this craziness together, but don’t dare ask me about it.

Meteos‘ simple match-three mechanics is lengthened out into a full game with stages that vary up the gravity of the skywards-moving blocks and, as referred to in the Lumines series, skins for the various stages. These alterations have no bearing on the core mechanic, and, as such, Meteos‘ sole asset feels stretched beyond its scope. Sora Ltd attempts to flesh Meteos out with a ridiculous story and locked bonus content, however, these additions, much like the changing skins and minor physics changes are artificial at best. New stages, bonuses and other extras are just distractions which impede the experience more than enhance, particularly when the block designs animate and become incongruous with each other.

I got many good hours of gameplay out of Meteos‘ enjoyable match-three mechanic alone, which suggests that the self-sufficient gameplay is better suited to a downloadable format with an infinite mode and clear block designs. This is an awesome game with frivolous additions to meet the retail release.

Donkey Kong Jungle Beat

How can one not enjoy the unashamedly bombastic nature of Donkey Kong Jungle Beat? It’s a game that I haven’t the energy to finish over a regular duration, so I’ve decidedly been hitting the bongos every couple of months for the past few years now. Not quite a ritual, just something worth pulling out on occasion.

Donkey Kong Jungle Beat is one of those games where the visual presentation matches the gameplay really well. Gameplay is a patchwork quilt of set piece 2D platforming concepts (riding animals, using the parachute and fans, the boss battles) stitched together around the surprisingly excellent bongo-based platforming. The standard platforming constitutes the majority of gameplay, as does the environmental/elemental-based theme within the visual presentation. As frequently as DK switches to a new mode of play, does the visual style pertain some sort of individualistic flair (which may not adhere to the rest of the style guide). Detailed textures and neat technical effects are mashed in amongst plain textures and simple modeling. The gameplay is as diverse as the visual showcase, consolidating the game’s irreverent style.

As a brief conclusion, the fact that Nintendo can create a supremely enjoyable platformer with two buttons and a clap technique is a testament to their ingenuity.

Final Fantasy: Rings of Fate

In contrast to how I usually comment on games, I haven’t didn’t play Rings of Fate for very long and am already writing about it. After an hour or so of playing (and confirming impressions with my brother who completed this game years ago) I decided that it wasn’t worth my time to play Rings of Fate. It’s simply hack and slash filler, that’s all. From the onset, Rings of Fate seems like a great kids game, but the story is so condescending and the voice acting so ear piercingly awful that I was forced to preemptively give up. Players loathe games which make them feel stupid and adore games which make them feel intelligent, and this was a game that looked down on me, so I have no sympathy for it and neither should the children.

Attempting to Understand Everyday Shooter

April 11th, 2010

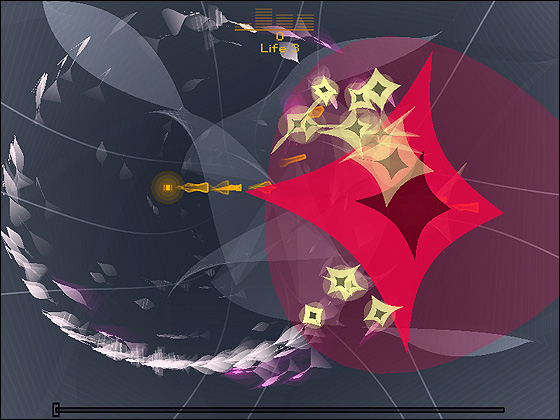

Everyday Shooter is a game which has touched me profoundly. I can’t believe that I’d be saying such things about an arena shooter, an unassuming, independently-developed one at that. In regards to my former post on games as art, Everyday Shooter excels at bridging the mechanical and contextual while never breaking equilibrium. As someone who despises the pontification of games like Flower in lieu of constructive analysis, I’m going to try my best to provide some sensible commentary on the inner-workings of this title. I’m pretty weary that I’m about to fail though as, despite the fact that I’ve been stewing over Everyday Shooter for the past year that I’ve been playing it, I’m afraid that I still can’t quite wrap my head around what makes it work. It’s really simple, I’m sure but it hasn’t hit me yet, so let’s make a go of it anyways.

General Gameplay

Everyday Shooter is a twin-stick arcade shooter in the vein of Geometry Wars. You use one stick to move your ship, a pixel, and the other to blast threats in any direction. Your movement speed decreases when doing both actions at the same time, facilitating tactical defense and escape strategies.

Inspired by Every Extend Extra, Everyday Shooter employs a combo system whereby destroying certain objects will cause a chain reaction of explosions. The combo system varies from stage to stage. In the first stage (the name escapes me now), explosions from destroying satellite-looking creatures remain on screen for a period of time where the player can temporarily fuel the blast will bullets, any fodder which touch the blast radius add to the combo.

Most enemy types leave a small pellet after they’ve been hit which your ship can collect (pellets have a mild magnetism to your ship) for points. After reaching a certain score, you gain a life and the threshold for the next 1up increases. These pellets can be later used as points to extend the default lives count of your pixel. It is intended that players will have to play the initial levels continually to slowly earn enough points to afford the necessary number lives to crawl their way to the final stages.

Since you’re constantly replaying the same levels to nudge yourself a little further and add credits to the bank for starter lives and an increased chance of breaking into the next stage, one might assume that Everyday Shooter is a repetitive experience, however each stage reacts organically to the player’s success. If you’re scoring well, more enemies will spawn, they’ll spawn additional little factories to spawn more units and flood you. Although the overall template is the same, because you never play two games exactly the same, your experience on each replay differs significantly.

Visual Significance

Each level plays out like an interactive piece of art pertaining a sense of narrative through the patterns of the procedurally-generated shapes. The shapes are sometimes representative of real life objects (birds, bugs, tanks) and sometimes metaphoric. No matter the representation, the shapes act as cogs in the piece’s overall pattern. Although the underlying themes of some levels are more obvious than others, the 8 pieces leave a wide window of interpretation for the player to relate to. Since the designer, Jonathan Mak, is a programmer and not an artist, all of the art in the game is procedurally-generated which contribute to the strikingly natural and organic appearance.

And the Magic…

It’s the thread that ties these two worlds together which is most important. Each level in Everyday Shooter is a dual layered system: a combo and chaining system which corresponds to the visual and aural system. The arena shooter is the interface for you to commandeer the artwork. Your ship is your brush and the bullet fire the ink, so when you play the arena shooter you channel the artwork and the artwork creates a mood which draws you back in to the arena shooter. These two halves have a striking, self-sustained unity. The aural and visual landscapes not only convey information to the read, they’re rich and palatable to the senses, they convey an emotion which the player subsumes and becomes enveloped in. The shooting itself is organic and challenging and the presentation is meaningful and informative so the two halves work together to create a very dense type of game. On completing a round of Everyday Shooter I feel an emotional weight in my chest, and I think that this is how it happens.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99