Defining Okami’s Individualism Part #1

February 8th, 2010

[Okami’s massive 40+ hour play time is the sole reason for the lack of game-related posts on here in recent weeks. I always begin writing after I’ve finished a game and Okami‘s enduring length over the past several months has forced me to continually postpone my writing. However, I think it’s been well worth it as I have a slew of analysis lined up.]

[Okami’s massive 40+ hour play time is the sole reason for the lack of game-related posts on here in recent weeks. I always begin writing after I’ve finished a game and Okami‘s enduring length over the past several months has forced me to continually postpone my writing. However, I think it’s been well worth it as I have a slew of analysis lined up.]

If you’re unfamiliar with Okami, or just need a refresher, then the video below should prepare you for the analysis (further below) as well as the other articles which’ll follow in the coming days. For interest’s sake, I played the PS2 version.

Personally speaking, many of my favourite games are titles which take an established formula, particularly formula of a traditional vintage, and restructure it to create an experience which feels both reminiscent and refreshing. An obvious and very literal example of such a game is Grand Theft Auto: Chinatown Wars. GTA:CW readapts the overhead 2D gameplay from GTA and GTA2 to the DS platform as well as fitting the formula with the modern design amenities which have developed out of the 3D titles. A less explicit example is Metroid Prime, which forwent the platforming genre whilst keeping exploration, the series’ most defining element, at the root of the experience. It takes an astute team of developers to understand what made the essence of the original subject matter (series, genre, approach) so special and then reinterpret this essence into a new format.

Okami, as you’ve probably guessed, is this type of game. Okami takes the established Zelda framework and tailors it in a way which feels new and exciting. To simply label Okami as a Zelda-styled adventure is probably a bit discrediting, as its divergences are what contribute to the game’s excellence. Let’s take a look at the way Okami separates itself, not just from Zelda, but from the established norm, as it’s here where Okami flourishes.

Movement

Being a wolf, Amaterasu moves faster than humans and therefore faster than most other video game characters (particularly in the RPG genre). Amaterasu’s speed is somewhere between the average speed of a car and a human walk, which is a little unusual for video games by virtue of the fact that either of those two ends tend to act as the avatar, rather than a middle point.

One could argue that Amaterasu has a strong likeness in movement to Epona, Link’s horse from the Zelda series. However, Epona functionally plays the same role as a vehicle. She is peripheral, whereas, Amaterasu alone achieves both the function of Link (slower, more refined movement) and Epona (a fast sprint for quicker travel). So, just from the standpoint of movement, Amaterasu is a very unique character.

Division and Dynamic of the Overworld

Okami‘s overworld, the land of Nippon, is broken apart into a series of smaller hub areas, rather than being contained within a single overworld. As we’ve learnt from the past 13 years of Zelda titles, a single, sparsely populated overworld, be it a field or an ocean, only increases the time of low player participation*. The segregation of Nippon into a series of smaller hubs therefore creates a different dynamic for these isolated areas. Firstly, on a technical level, more data can be rendered into a smaller area, allowing the developers to fill each hub more densely with interesting stuff like environment, characters and activities. Secondly, on a spatial level, the more confined space cuts the travel time between towns and other areas of interest, this is accommodated by Amaterasu’s fast-paced sprint. As a result, time spent in the overworld is not downtime, but rather a time for the player to engage in the abundance of choice that the Okami offers them.

More Killer Less Filler

The amount of time and obligation required to attend to these aforementioned activities (those tangental to the main quest), offer the player different degrees of engagement. Players can spend a few minutes fixing up the environment with their celestial brush or spend much longer hunting down collectables or partaking in mini-games.

The great thing about Okami is that everywhere (not just in the “overworld”) is full of these microcosms of activity. This is predominately served by the celestial brush which can heal various parts of the environment, but also the incredible number of collectables such a ornaments, stray beads, fish, dojo scrolls…the list is rather extensive, and as discussed in The New Gamer, it can sometimes feel like you’re gorging on excess.

What this means is that every inch of land in Okami is dense with gameplay, unlike in the majority of other games where the landscape is not a harvester for gameplay, instead often playing a meaningless, passive role, ie. Uncharted.

*Before you mention it, I am aware that Zelda:Twilight Princess‘ main overworld is split into several small hubs, however this appears to be so for technical reasoning, rather than functional. The overworlds between the two games are very different.

Additional Readings

Leap of Faith – 1UP Okami Cover Story

‘Giving the Context’

February 5th, 2010

When writing any sort of game evaluation (preview, review, analysis piece, critique, etc.), the writer begins by explaining how the game works or what happens in the game. This is what I’ll call ‘giving the context’. As much as ‘giving the context’ is an essential component for this type of writing, it’s often the least interesting part of the article for both reader and writer. Sadly, the majority of evaluative articles consist almost entirely of context and share little insight with the reader. This is why we often moan so loudly over reviews; the reviewers rarely justify their comments with explanation and the readers therefore become suspicious. (Alternatively, the readers don’t read and become suspicious anyways).

The reason why context is boring to read falls in line with similar comments made by Jim Gee in his book Good Games and Good Learning. Players don’t learn how to play a game by reading the instruction manual—no one ever looks at the manual if they can help it, they just jump straight in. People learn the rules of a game not by reading about it, but by playing. Reading an instruction manual or game review in the pursuit of understanding the operation of a game is counterproductive, because it’s difficult to learn anything through static text alone.

I’m sure that you’ve probably met this frustration before, most likely through school, but more to the point, after reading a review and yet still not understanding the fundamental rules of a game, let alone why it’s good or bad or is worthy of your green paper. (Perhaps this is why video reviews are now so popular; they inherently provide continuous context throughout the review). I’ve certainly felt this way many times, just recently after reading several reviews on Bioware’s two most recent games: Dragon Age Origins and Mass Effect 2, I still have no grasp on the core gameplay, particularly in Dragon Age. I think it’s about time I ought to just play the games for myself.

Personally, I believe that as writers it’s our job to make this mandatory part of the job as quick and effective as possible, so that we can get down to the business of giving meaning to the game through our critique, analysis and observations.

Anyone can—and does—write the synopsis of a plot or explain what happens in a game, provided that you’re a sound writer, giving context is pretty easy, analysis, however, is the most difficult part of the job which is why analysis it’s often the part which is most lacking. Therefore, the great majority of games writing serves very little purpose beyond condensing manuals or expanding PR bullet points into sentences, because that’s what naturally comes easiest.

On an side, I think this also explains why it’s difficult to have an engaging conversation with other people about games. Good games discussion requires one of two things, preferably both: 1) shared knowledge of context and evaluation (hopefully at a rather deep level) 2) the mutual patience required to listen to someone explain a complicated rule system to you through spoken language and then evaluate the rule system. It’s really tricky, as I’m sure you all know which is why most discussion amounts to “wasn’t it cool when…”.

One of my goals this year is to trim down the amount of context in my ‘Game Discussion’ articles. Of course, I want it to remain sufficient, just in fewer words, if possible. So as a footnote to this article, I’ve written a list of measures which I hope to adopt in my future writing, this may also be useful for you too as either a critical reader or a writer. If you have any further suggestions, I’d be happy to hear them, so please leave a comment in the box below:

- Use as few words as possible to convey as much information as possible.

- KISS ? Keep it simple stupid, people have to make sense of what you’re saying, try to stay away from esoteric or abstract language.

- Use language (particularly verbs) which stylise mechanics and other integral parts of the game which can easily be stylised. These improve readability and understanding, and also make the writing more palatable.

- Or if you can’t do the above, make up your own verb to describe an action rather than continuously using 3-4 words to describe a single action or event. This avoids repetition.

- If there is a similar game or gameplay style which is adapted into your game then refer to it. eg. Gears of War style shooters, Geometry Wars clone.

- Be specific and accurate. Saying ‘an arena shooter’ saves on having to explain that it’s a shoot ’em up in a box.

- Use images and video of the gameplay itself. This is the easiest method for setting context. If you’re going to jump straight into analysis, assuming that the audience is already immersed in the game, then maybe a video review from Youtube or Gametrailers would prove useful.

- Dot points or diagrams are also a great idea Critical Gaming is a wonderful example of this technique, and in fact is the ideal example of a context-minimal, analysis-rich blog.

Pixel Hunt Re-examined (+ Some Words on Retroaction)

February 4th, 2010

![]()

Back in April last year I heavily criticised endearing Australian multiplatform games magazine, Hyper, while simultaneously throwing praise to side-line act Pixel Hunt. Pixel Hunt is worthy comparison to Hyper. I mean, it’s free, conservative games writing brought to you by Hyper contributors with enough leeway to go rogue without the uncomfortable snapback of their part-time employers. In particular, I commented on Pixel Hunt’s skew for a more progressive, supposedly analytical approach to games writing.

My comments were made under the observation of the magazine’s steady progression towards a more feature-rich, analysis-heavy format that could, in a few issues, develop it into an authority, you know, something worth repeated reading in this competitive field of non-commercial games writing. Unfortunately, I feel that since then the promise has disappeared as the magazine settles down into a familiar template. Yeah, I’m sure you know the one.

![]()

Don’t get me wrong, I agree with the comments made by Dylan Burns (editor) in his opening editorial to issue #10 “Our team of writers is, I believe, amongst the most passionate in this country”. They’re talented too. Really clean writers which I appreciate, even though it’s not my most preferred style as a reader. Yet despite all the talent and good writers they house, the format is suffocation.

I’m kinda tired of harping on the inherent flaws of the writing format adopted by the enthusiast and professional media alike (you’ve probably heard me talk about it before, anyways), so let’s just bang out a list, it’ll be easier:

- Pixel Hunt is bloated by an unhealthy number of reviews

- 85-95% of the content in each review tells the reader what happens in the game rather than explaining how the game is good/bad or how the game achieves a desired effect, what effect the game had on the player or just any general insight, some reviewers are better than others in this regard

- Considering the late release of the magazine in respects to rival formats, marketing, demos and the release of the games themselves, most readers are likely to already know what happens in the game, and considering this part constitutes the majority of the magazine’s content, there is little reason to bother reading it at all

- The amount of space given to the editorials is criminal, which is why they all cover very simplistic arguments

- The features are the magazine’s primary selling point* and more attention needs to be paid here

- Most of the writers sound the same (this is obviously subjective, Hyper has always suffered the same problem, I feel)

None of this is designed to offend, but rather explain my own discontent with the magazine, because I believe that it’s capable of much more. Hmm, let’s take another online magazine, Retroaction, as a counter example to Pixel Hunt:

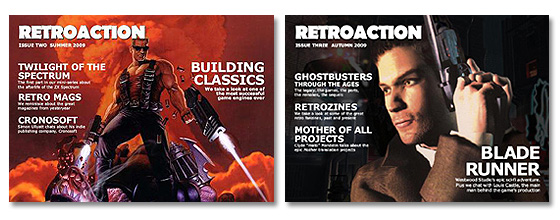

Retroaction is a new, retro/indie games e-magazine run by a handful of retro game enthusiasts, most of which have little writing experience. Although the quality of writing has improved in leaps and bounds since the first issue (they’re up to their 3rd, so far), it’s still downright atrocious at times. Furthermore, Retroaction’s reviews are almost entirely full of information with very little evaluation to speak of, and most of the appraisal is glowing or at least generous. Did I mention that the layout and visual design leaves a little to be desired too? Yet despite the lacking amenities, I often come back to re-read articles in Retroaction because they’re original and therefore insightful, even within the retro/indie games niche. A two part feature on the ZX Spectrum’s Russian knock-offs and resulting indie development scene over the past 20 years is not only interesting, it’s material that can’t easily be found anywhere else. A lack of analysis in the reviews isn’t imperative to Retroaction, unlike with Pixel Hunt, because the information, the “here’s what happens in the game part”, is sufficient on its own, because the games themselves are largely unheard of in the mainstream**.

Conformity does not equate to incentive and it’s for this reason, for Pixel Hunt’s pursuit of the status quo of enthusiast writing, that my interest (and prior recommendation) has diminished.

On the other hand, I hope that my criticisms haven’t dissuaded you too much, because as it turns out I actually contributed an article to the latest issue (issue #10, download here, 38mbs). With a dash of irony though, I was wrongly credited. (And no, before you ask, the error didn’t spur me on to write this piece). I wrote the article on Dragon Quest IV at the end of the magazine, NOT Daniel Golding. You might know Daniel as the guy who gained rapturous attention after mapping out the self-important “Brainysphere”. You could’ve fooled me though, as I read half way into the article before realising I’d written it myself, and there I was feeling envious and all, shucks. I’m surprised though, honestly, it really blends in with the rest of the content, which is strange given that the nature of the writing isn’t usually part of my shtick. So check it out for that reason, or to spot the unedited spelling error…

*Can it be considered a selling point if it’s free? Probably not. Either way, the features are generally good.

**I’m starting to understand now why the majority of blogs in my RSS feed reader are retro or alternative-based. Conventional games writing is simply that (however, it can be analysis-rich AND progressive, as is the case with much of Eurogamer‘s content, for example), and even within the bloggosphere, good analysis is scattered, whereas the retro and alternative coverage is often always interesting.

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99

Game Design Companion: A Critical Analysis of Wario Land 4 - $7.99 Level Design: Processes and Experiences

Level Design: Processes and Experiences Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99

Speed Boost: The Hidden Secrets Behind Arcade Racing Design - $5.99 Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99

Adventures in Games Analysis: Volume I - $5.99